Exception handling in C++ is a well-unschooled topic if you observe initial stages of the learning curve. There are numerous tutorials available online on exception handling in C++ with example. But few explains what you should not do & intricacies around it. So here, we will see some intricacies, from where & why you should not throw an exception along with some newer features introduced in Modern C++ on exception handling with example. I am not an expert but this is what I have gained from various sources, courses & industry experiences.

/!\: Originally published @ www.vishalchovatiya.com.

In the end, we will see the performance cost of using an exception by a quick benchmark code. Finally, we will close the article with Best practices & some CPP Core Guidelines on exception handling.

Note: we will not see anything regarding a dynaic exception as it deprecated from C++11 and removed in C++17.

Terminology/Jargon/Idiom you may face

- potentially throwing: may or may not throw an exception.

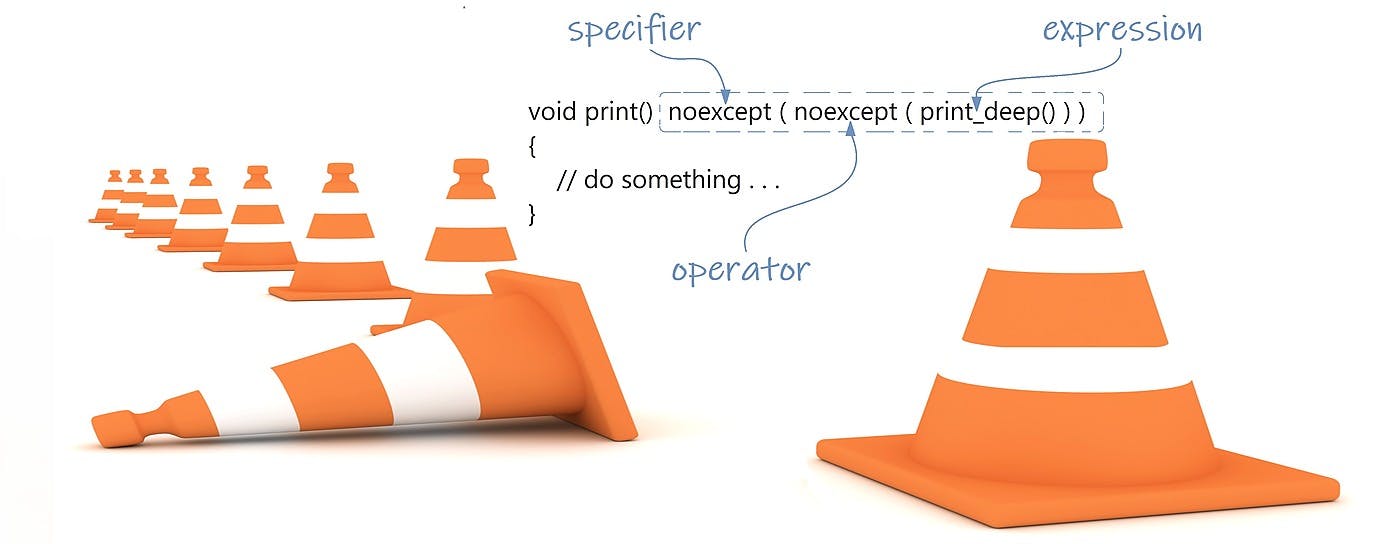

- noexcept: this is specifier as well as operator depending upon where & how you use it. Will see that later.

- RAII: Resource Acquisition Is Initialization is a scope-bound resource management mechanism which means resource allocation is done by the constructor & resource deallocation is done by the destructor during the defined scope of the object. I know it’s a terrible name but very powerful concept.

- Implicitly-declared special member functions: I think this need not require any introduction.

1. Implement copy and/or move constructor while throwing user-defined type object

struct demo

{

demo() = default;

demo(demo &&) = delete;

demo(const demo &) = delete;

};

int main()

{

throw demo{};

return 0;

}- Upon throw expression, a copy of the exception object always needs to be created as the original object goes out of the scope during the stack unwinding process.

- During that initialization, we may expect copy elision (see this) – omits copy or move constructors (object constructed directly into the storage of the target object).

- But even though copy elision may or may not be applied you should provide proper copy constructor and/or move constructor which is what C++ standard mandates(see 15.1). See below compilation error for reference:

error: call to deleted constructor of 'demo'

throw demo{};

^~~~~~

note: 'demo' has been explicitly marked deleted here

demo(demo &&) = delete;

^

1 error generated.

compiler exit status 1- Above error stands true till C++14. Since C++17, If object thrown is a prvalue, the move/copy constructor call is optimized out i.e. copy elision.

- If we catch an exception by value, we may also expect copy elision(compilers are permitted to do so, but it is not mandatory). The exception object is an lvalue argument when initializing catch clause parameter.

TL;DR

class used for throwing the exception object needs copy and/or move constructors

2. Be cautious while throwing an exception from the constructor

struct base

{

base(){cout<<"base\n";}

~base(){cout<<"~base\n";}

};

struct derive : base

{

derive(){cout<<"derive\n"; throw -1;}

~derive(){cout<<"~derive\n";}

};

int main()

{

try{

derive{};

}

catch (...){}

return 0;

}- When an exception is thrown from a constructor, stack unwinding begins, destructors for the object will be called only & only if an object is created successfully. So be caution with dynamic memory allocation here. In such cases, you should use RAII.

base

derive

~base- As you can see in the above case, the destructor of derive is not executed, Because, it is not created successfully.

struct base

{

base() { cout << "base\n"; }

~base() { cout << "~base\n"; }

};

struct derive : base

{

derive() = default;

derive(int) : derive{}

{

cout << "derive\n";

throw - 1;

}

~derive() { cout << "~derive\n"; }

};

int main()

{

try{

derive{0};

}

catch (...){}

return 0;

}- In the case of constructor delegation, it is considered as the creation of object hence destructor of derive will be called.

base

derive

~derive

~baseTL;DR

When an exception is thrown from a constructor, destructors for the object will be called only & only if an object is created successfully

3. Avoid throwing exceptions out of a destructor

struct demo

{

~demo() { throw std::exception{}; }

};

int main()

{

try{

demo d;

}

catch (const std::exception &){}

return 0;

}- Above code seems straight forward but when you run it, it will be terminated as shown below rather than catching the exception. Reason for this is destructors are by default

(i.e. non-throwing)noexcept

$ clang++-7 -o main main.cpp

warning: '~demo' has a non-throwing exception specification but can still

throw [-Wexceptions]

~demo() { throw std::exception{}; }

^

note: destructor has a implicit non-throwing exception specification

~demo() { throw std::exception{}; }

^

1 warning generated.

$

$ ./main

terminate called after throwing an instance of 'std::exception'

what(): std::exception

exited, aborted

will solve our problem as below.noexcept(false)

struct X

{

~X() noexcept(false) { throw std::exception{}; }

};- But don’t do it. Destructors are by default non-throwing for a reason, and we must not throw exceptions in destructors unless we catch them inside the destructor.

Why you should not throw an exception from a destructor?

Because destructors are called during stack unwinding when an exception is thrown, and we are not allowed to throw another exception while the previous one is not caught – in such a case

std::terminate- Consider the following example for more clarity.

struct base

{

~base() noexcept(false) { throw 1; }

};

struct derive : base

{

~derive() noexcept(false) { throw 2; }

};

int main()

{

try{

derive d;

}

catch (...){ }

return 0;

}- An exception will be thrown when the object d will be destroyed as a result of RAII. But at the same time destructor of base will also be called as it is sub-object of derive which will again throw an exception. Now we have two exceptions at the same time which is invalid scenario &

will be called.std::terminate

- There are some type trait utilities like

,std::is_nothrow_destructible

, etc. fromstd::is_nothrow_constructible

by which you can check whether the special member functions are exception-safe or not.#include<type_traits>

int main()

{

cout << std::boolalpha << std::is_nothrow_destructible<std::string>::value << endl;

cout << std::boolalpha << std::is_nothrow_constructible<std::string>::value << endl;

return 0;

}TL;DR

1. Destructors are by default(i.e. non-throwing).noexcept

2. You should not throw exception out of destructors because destructors are called during stack unwinding when an exception is thrown, and we are not allowed to throw another exception while the previous one is not caught – in such a casewill be called.std::terminate

4. Rethrowing/Nested exception handling with std::exception_ptr( C++11) example

This is more of a demonstration rather the best practice of the nested exception scenario using

std::exception_ptrstd::exceptionstd::exception_ptrtrycatchvoid print_nested_exception(const std::exception_ptr &eptr=std::current_exception(), size_t level=0)

{

static auto get_nested = [](auto &e) -> std::exception_ptr {

try { return dynamic_cast<const std::nested_exception &>(e).nested_ptr(); }

catch (const std::bad_cast&) { return nullptr; }

};

try{

if (eptr) std::rethrow_exception(eptr);

}

catch (const std::exception &e){

std::cerr << std::string(level, ' ') << "exception: " << e.what() << '\n';

print_nested_exception(get_nested(e), level + 1);// rewind all nested exception

}

}

// -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

void func2(){

try { throw std::runtime_error("TESTING NESTED EXCEPTION SUCCESS"); }

catch (...) { std::throw_with_nested(std::runtime_error("func2() failed")); }

}

void func1(){

try { func2(); }

catch (...) { std::throw_with_nested(std::runtime_error("func1() failed")); }

}

int main()

{

try { func1(); }

catch (const std::exception&) { print_nested_exception(); }

return 0;

}

// Will only work with C++14 or above- Above example looks complicated at first, but once you have implemented nested exception handler(i.e.

). Then you only need to focus on throwing the exception usingprint_nested_exception

function.std::throw_with_nested

exception: func1() failed

exception: func2() failed

exception: TESTING NESTED EXCEPTION SUCCESS- The main thing to focus here is

function in which we are rewinding nested exception usingprint_nested_exception

&std::rethrow_exception

.std::exception_ptr

is a shared pointer like type though dereferencing it is undefined behaviour. It can hold nullptr or point to an exception object and can be constructed as:std::exception_ptr

std::exception_ptr e1; // null

std::exception_ptr e2 = std::current_exception(); // null or a current exception

std::exception_ptr e3 = std::make_exception_ptr(std::exception{}); // std::exception- Once

is created, we can use it to throw or re-throw exceptions by callingstd::exception_ptr

as we did above, which throws the pointed exception object.std::rethrow_exception(exception_ptr)

TL;DR

1.extends the lifetime of a pointed exception object beyond a catch clause.std::exception_ptr

2. We may useto delay the handling of a current exception and transfer it to some other palaces. Though, practical usecase ofstd::exception_ptris between threads.std::exception_ptr

5. Use noexcept specifier vs operator appropriately

- I think this is an oblivious concept among the other concepts of the C++ exceptions.

- noexcept specifier & operator came in C++11 to replace deprecated(removed from C++17) dynamic exception specification.

void func() throw(std::exception); // dynamic excpetions, removed from C++17

void potentially_throwing(); // may throw

void non_throwing() noexcept; // "specifier" specifying non-throwing function

void print() {}

void (*func_ptr)() noexcept = print; // Not OK from C++17, `print()` should be noexcept too, works in C++11/14

void debug_deep() noexcept(false) {} // specifier specifying throw

void debug() noexcept(noexcept(debug_deep())) {} // specifier & operator, will follow exception rule of `debug_deep`

auto l_non_throwing = []() noexcept {}; // Yeah..! lambdas are also in partynoexcept specifier

I think this needs no introduction it does what its name suggests. So let’s quickly go through some pointers:

I think this needs no introduction it does what its name suggests. So let’s quickly go through some pointers:

- Can be used for normal functions, methods, lambda functions & function pointer.

- From C++17, function pointer with noexcept can not points to potentially throwing function.

- Finally, don’t use

specifier for virtual functions in a base class/interface because it enforces restriction for all overrides.noexcept - Don’t use noexcept unless you really need it. “Specify it when it is useful and correct” – Google’s cppguide.

noexcept operator & what is it used for?

- Added in C++11,

operator takes an expression (not necessarily constant) and performs a compile-time check determining if that expression is non-throwing (noexcept

) or potentially throwing.noexcept - The result of such compile-time check can be used, for example, to add

specifier to the same category, higher-level functionnoexcept

or in if constexpr.(noexcept(noexcept(expr))) - We can use

operator to check if some class hasnoexcept

constructor, noexcept copy constructor, noexcept move constructor, and so on as follows:noexcept

class demo

{

public:

demo() {}

demo(const demo &) {}

demo(demo &&) {}

void method() {}

};

int main()

{

cout << std::boolalpha << noexcept(demo()) << endl; // C

cout << std::boolalpha << noexcept(demo(demo())) << endl; // CC

cout << std::boolalpha << noexcept(demo(std::declval<demo>())) << endl; // MC

cout << std::boolalpha << noexcept(std::declval<demo>().method()) << endl; // Methods

}

// std::declval<T> returns an rvalue reference to a type- You must be wondering why & how this information will be useful?

This is more useful when you are using library functions inside your function to suggest compiler that your function is throwing or non-throwing depending upon library implementation. - If you remove constructor, copy constructor & move constructor, it will print true reason being implicitly-declared special member functions are always non-throwing.

TL;DRspecifier & operator are two different things.noexceptoperator performs a compile-time check & doesn’t evaluate the expression. Whilenoexceptspecifier can take only constant expressions that evaluate to either true or false.noexcept

6. Move exception-safe with std::move_if_noexcept

std::move_if_noexceptstruct demo

{

demo() = default;

demo(const demo &) { cout << "Copying\n"; }

// Exception safe move constructor

demo(demo &&) noexcept { cout << "Moving\n"; }

private:

std::vector<int> m_v;

};

int main()

{

demo obj1;

if (noexcept(demo(std::declval<demo>()))){ // if moving safe

demo obj2(std::move(obj1)); // then move it

}

else{

demo obj2(obj1); // otherwise copy it

}

demo obj3(std::move_if_noexcept(obj1)); // Alternatively you can do this----------------

return 0;

}- We can use

to check ifnoexcept(T(std::declval<T>()))

’s move constructor exists and isT

in order to decide if we want to create an instance ofnoexcept

by moving another instance of T (usingT

).std::move - Alternatively, we can use

, which usesstd::move_if_noexcept

operator and casts to either rvalue or lvalue. Such checks are used innoexcept

and other containers.std::vector - This will be useful while you are processing critical data which you don’t want to lose. For example, we have critical data received from the server that we do not want to lose it at any cost while processing. In such a case, we should use

which will move ownership of critical data only and only if move constructor is exception-safe.std::move_if_noexcept

TL;DR

Move critical object safely withstd::move_if_noexcept

7. Real cost of exception handling in C++ with benchmark example

Despite many benefits, most people still do not prefer to use exceptions due to its overhead. So let’s clear it out of the way:

static void without_exception(benchmark::State &state){

for (auto _ : state){

std::vector<uint32_t> v(10000);

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < 10000; i++) v.at(i) = i;

}

}

BENCHMARK(without_exception);//----------------------------------------

static void with_exception(benchmark::State &state){

for (auto _ : state){

std::vector<uint32_t> v(10000);

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < 10000; i++){

try{

v.at(i) = i;

}

catch (const std::out_of_range &oor){}

}

}

}

BENCHMARK(with_exception);//--------------------------------------------

static void throwing_exception(benchmark::State &state){

for (auto _ : state){

std::vector<uint32_t> v(10000);

for (uint32_t i = 1; i < 10001; i++){

try{

v.at(i) = i;

}

catch (const std::out_of_range &oor){}

}

}

}

BENCHMARK(throwing_exception);//------------------------------------------ As you can see above,

&with_exception

has only a single difference i.e. exception syntax. But none of them throws any exceptions.without_exception - While

does the same task except it throws an exception of typethrowing_exception

in the last iteration.std::out_of_range - As you can see in below bar graph, the last bar is slightly high as compared to the previous two which shows the cost of throwing an exception.

- But the cost of using exception is zero here, as the previous two bars are identical.

- I am not considering the optimization here which is the separate case as it trims some of the assembly instructions completely. Also, implementation of compiler & ABI plays a crucial role. But still, it is far better than losing time by setting up a guard(

strategy) and explicitly checking for the presence of error everywhere.if(error) - While in case of exception, the compiler generates a side table that maps any point that may throw an exception (program counter) to the list of handlers. When an exception is thrown, this list is consulted to pick the right handler (if any) and the stack is unwound. See this for in-depth knowledge.

- By the way, I am using a quick benchmark & which internally uses Google Benchmark, if you want to explore more.

- First and foremost, remember that using try and catch doesn’t actually decrease performance unless an exception is thrown.It’s “zero cost” exception handling – no instruction related to exception handling is executed until one is thrown.

- But, at the same time, it contributes to the size of executable due to unwinding routines, which may be important to consider for embedded systems.

TL;DR

No instruction related to exception handling is executed until one is thrown so using/trydoesn’t actually decrease performance.catch

Best practices & some CPP Core Guidelines on exception handling

Best practices for C++ exception handling

- Ideally, you should not throw an exception from the destructor, move constructor or swap like functions.

- Prefer RAII idiom for the exception safety because in case of exception you might be left with

– data in an invalid state, i.e. data that cannot be further read & used;

– leaked resources such as memory, files, ids, or anything else that needs to be allocated and released;

– corrupted memory;

– broken invariants, e.g. size function returns more elements than actually held in a container.

- Avoid using raw new & delete. Use solutions from the standard library, e.g.

,std::unique_pointer

,std::make_unique

,std::fstream

, etc.std::lock_guard - Moreover, it is useful to split your code into modifying and non-modifying parts, where only the non-modifying part can throw exceptions.

- Never throw exceptions while owing some resource.

Some CPP Core Guidelines

- E.1: Develop an error-handling strategy early in a design

- E.3: Use exceptions for error handling only

- E.6: Use RAII to prevent leaks

- E.13: Never throw while being the direct owner of an object

- E.16: Destructors, deallocation, and swap must never fail

- E.17: Don’t try to catch every exception in every function

- E.18: Minimize the use of explicit try/catch

- 26: If you can’t throw exceptions, consider failing fast

- E.31: Properly order your catch-clauses