Authors:

(1) Ajit Jain, Texas A&M University, USA; Current affiliation: Audigent;

(2) Andruid Kerne, Texas A&M University, USA; Current affiliation: University of Illinois Chicago;

(3) Nic Lupfer, Texas A&M University, USA; Current affiliation: Mapware;

(4) Gabriel Britain, Texas A&M University, USA; Current affiliation: Microsoft;

(5) Aaron Perrine, Texas A&M University, USA;

(6) Yoonsuck Choe, Texas A&M University, USA;

(7) John Keyser, Texas A&M University, USA;

(8) Ruihong Huang, Texas A&M University, USA;

(9) Jinsil Seo, Texas A&M University, USA;

(10) Annie Sungkajun, Illinois State University, USA;

(11) Robert Lightfoot, Texas A&M University, USA;

(12) Timothy McGuire, Texas A&M University, USA.

Table of Links

-

Prior Work and 2.1 Educational Objectives of Learning Activities

-

3.1 Multiscale Design Environment

3.2 Integrating a Design Analytics Dashboard with the Multiscale Design Environment

-

5.1 Gaining Insights and Informing Pedagogical Action

5.2 Support for Exploration, Understanding, and Validation of Analytics

5.3 Using Analytics for Assessment and Feedback

5.4 Analytics as a Potential Source of Self-Reflection for Students

-

Discussion + Implications: Contextualizing: Analytics to Support Design Education

6.1 Indexicality: Demonstrating Design Analytics by Linking to Instances

6.2 Supporting Assessment and Feedback in Design Courses through Multiscale Design Analytics

We investigate how to use AI-based analytics to support design education. The analytics at hand measure multiscale design, that is, students’ use of space and scale to visually and conceptually organize their design work. With the goal of making the analytics intelligible to instructors, we developed a research artifact integrating a design analytics dashboard with design instances, and the design environment that students use to create them.

We theorize about how Suchman’s notion of mutual intelligibility requires contextualized investigation of AI in order to develop findings about how analytics work for people. We studied the research artifact in 5 situated course contexts, in 3 departments. A total of 236 students used the multiscale design environment. The 9 instructors who taught those students experienced the analytics via the new research artifact.

We derive findings from a qualitative analysis of interviews with instructors regarding their experiences. Instructors reflected on how the analytics and their presentation in the dashboard have the potential to affect design education. We develop research implications addressing: (1) how indexing design analytics in the dashboard to actual design work instances helps design instructors reflect on what they mean and, more broadly, is a technique for how AI-based design analytics can support instructors’ assessment and feedback experiences in situated course contexts; and (2) how multiscale design analytics, in particular, have the potential to support design education. By indexing, we mean linking which provides context, here connecting the numbers of the analytics with visually annotated design work instances.

1 INTRODUCTION

We investigate supporting design education by directly linking AI-based analytics with instances of students’ visual design work, in order to demonstrate what is measured. Our approach integrates an analytics dashboard with a collaborative design environment, where students and instructors create and comment on design work instances. The analytics at hand, multiscale design analytics, were introduced by Jain et al [40]. Multiscale design analytics measure how creative work, involving pictorial and textual elements, uses space and scale as organizing principles for presentation.

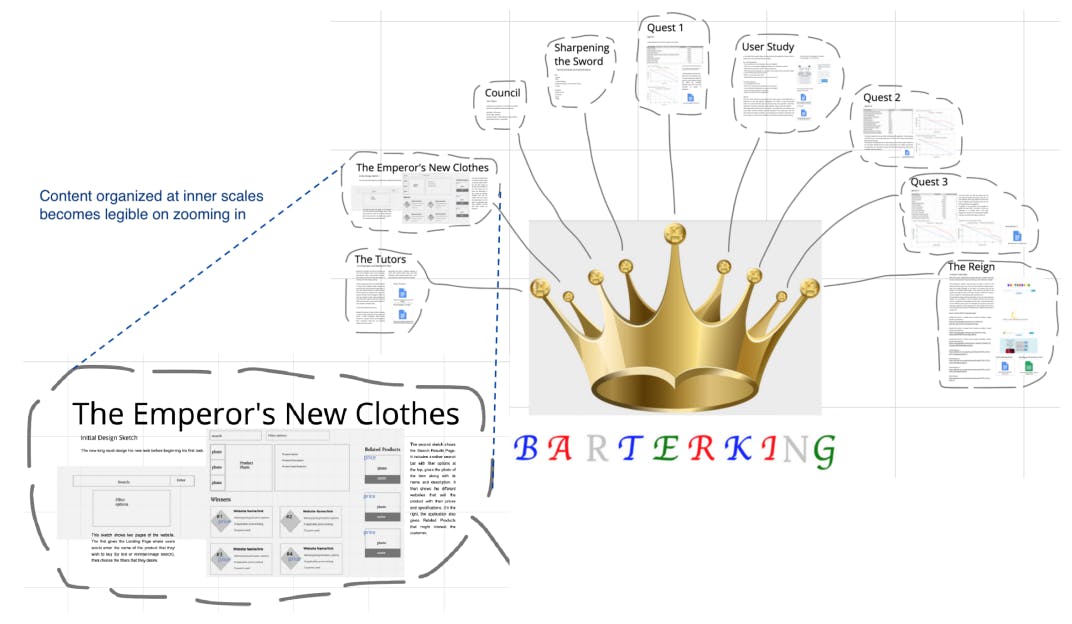

Multiscale design, according to Lupfer et al., is “the use of space and scale to explore and articulate relationships, [which] involves the juxtaposition and synthesis of diverse design elements” [51] (See example in Figure 1.). Scale refers to levels of magnification: elements at the same scale are “equally legible at the same viewport zoom” [52]. In practice, we observe that the juxtaposition and synthesis of elements, across scales, tends to look like nested spatial groups, i.e., clusters (Figure 1), of elements. Multiscale design is a strategy for what Tufte calls escaping the flatland of envisioning information, i.e., for increasing the legible dimensionality and density of information on the screen and page [73]. Prior investigations of design course contexts found that multiscale design supports students in creative ideation and reflection [52], schematic development of design proposals [51], and reuse of ideas across project deliverables [16].

In the diverse design education contexts we study, students work on creative, open-ended projects, where there can be multiple approaches to solving a problem, i.e., there is no fixed right answer. In fact, excellent answers are characterized by creativity, as well as skill, applied in the context of a particular design project problem. Working on such projects is known to be challenging [58]. Students need frequent assessment and feedback in order to make progress [47, 57]. Confounding these needs, in practice, is the trend of growing design education demands. Larger class sizes confront instructors with challenges in providing timely assessment and feedback [47]. Prior work shows that the use of AI can complement human work by providing the ability to process big data at speed [45]. The present research thus investigates AI-based multiscale design analytics as a means to support and scale instructors’ teaching efforts. Further, these analytics can form a basis for a constructivist learning model [42, 69], where students learn, through making, even when instructors are not there.

Consider a scenario. Alex is teaching a large class where students learn to use multiscale design. As students work on projects and put multiscale design principles and skills into practice, it is vital to provide them with feedback in early stages. However, due to time constraints, Alex is unable to continuously assess each student’s creative design work in detail. An AI-based system derives analytics that measure multiscale design characteristics in creative works, providing Alex with insights of how their students are using space and scale. The analytics computed for each design work assist them in providing quick, personalized feedback to individual students. Further, aggregate views of analytics—for each deliverable—assist Alex in identifying recurring problems students are facing in the course. Based on that, Alex develops timely pedagogical interventions, which progressively help improve student work and overall course outcomes.

In meeting the needs suggested by this scenario, we draw on recent AI research, which has shown promising results in recognizing creative visual design characteristics, such as nested hierarchies in spatially organized content elements [40, 59]. The research gap we address is a lack of prior understanding of how measures based on AI recognition can support instructor assessment and feedback experiences in design education. Consideration of the demands of Suchman’s precept of mutual intelligibility, here, how an AI recognizer is understood by people who use it, suggests conducting such an investigation in situated design course contexts. By combining understanding of multiscale design with AI recognition techniques, we are able to investigate how instructors respond to new forms of design education analytics. Our research questions are:

RQ1: How, if at all, can AI-based design analytics support instructors’ assessment and feedback experiences in situated course contexts?

RQ2: What specific value can AI-based multiscale design analytics provide to design instructors in situated course contexts?

AI-based design analytics are a relatively new technology, which is challenging to investigate, because performing studies in situated course contexts are demanding. Ethics prescribe that it is necessary to provide all the functionalities sufficient to support instructors and students so we do not hinder learning [17].

In order to contribute new knowledge about how AI-based design analytics have the potential to be useful, we take a Research through Design (RtD) [31, 84, 85] approach. RtD is suitable when the goal is to explore “what might be” rather than a “comparison or refutation” of certain techniques. As Zimmerman et al. explain, the focus of RtD is on making the “right thing”, not making the thing right [84]. Prior research [63] took a similar design probe approach to develop understandings of users’ experiences with animations explaining an algorithm’s functioning. The present research takes an ethical RtD approach by developing a highly functional ‘research artifact’ suitable for deployment in real world course contexts.

We studied the research artifact in 5 situated course contexts, in 3 departments, to understand how multiscale design analytics and their presentation can support instructors’ assessment and feedback. A total of 236 students used a multiscale design environment. The 9 instructors who taught those students experienced the analytics via the new research artifact dashboard integrated with the design environment. We derive findings from a qualitative analysis of interviews with instructors regarding their experiences. Based on the findings, we derive implications for making AI-based analytics useful in design and education. We conclude by reiterating the contributions of the present research and potential broad impacts.

This paper is