This is a Plain English Papers summary of a research paper called How AI Impacts Skill Formation. If you like these kinds of analysis, join AIModels.fyi or follow us on Twitter.

The productivity mirage

We live in a paradox that nobody wants to acknowledge. AI tools make us measurably more productive at immediate tasks, yet they might be quietly sabotaging our ability to work effectively with those same tools over time. A developer using an AI assistant to learn a new programming library finishes faster, checks off more tasks, and by every metric that gets reported in standup meetings, she's winning. But when she needs to debug that library independently six months later, or teach someone else how it works, or make decisions about whether to use it for a safety-critical system, something crucial is missing.

This paper reveals a counterintuitive finding through carefully controlled experiments: developers who use AI assistance while learning new skills end up understanding less, debugging worse, and aren't actually getting ahead in ways that matter.

The question of whether AI assistance helps or hurts learning seems straightforward until you stop to think about what "helping" actually means. A student using a calculator gets the right answer faster, but walking into an exam without one looks like a different story. The calculator created the appearance of mastery without building the underlying skill. AI assistance in professional settings works similarly, except nobody realizes the test is coming until competence actually matters: when systems fail, when decisions have to be made independently, when someone needs to explain their reasoning.

This matters because AI tools are being adopted at scale in workplaces right now. Everyone assumes they're purely beneficial. If a worker completes tasks faster with AI, organizations naturally celebrate that as a win. Productivity metrics go up. Onboarding timelines shrink. But this research asks what we're not measuring: What hidden costs might exist? What's the difference between a worker who finishes a task and a worker who understands what she's done?

The stakes are highest in domains where independent judgment matters most. In aviation, healthcare, security, and autonomous systems, you can't afford workers who are efficient at executing instructions but unable to think through novel problems. Yet these are precisely the domains where AI adoption pressure is greatest.

The learning deficit

To move from speculation to evidence, the researchers ran randomized controlled experiments with novice developers learning a new Python library called Trio. Some developers had access to an AI assistant while learning. Others didn't. Both groups completed the same tasks and took the same comprehension test afterward. This design isolates the pure effect of AI assistance on learning, removing confounds about who chose to use AI and why.

Figure 2 shows a worker completing tasks quickly with AI but the question mark about whether they actually understand what they've done

The question AI assistance raises: does productivity mask a learning deficit?

The results were stark. Participants who used AI showed significantly lower scores on three critical skill areas: conceptual understanding of how the library works, ability to read and interpret existing code, and debugging ability when things go wrong. These weren't marginal differences. They were substantial performance gaps.

Figure 1 shows the main result with decreased library-specific skills among AI users across conceptual understanding, code reading, and debugging

Conceptual understanding, code reading, and debugging all declined with AI assistance.

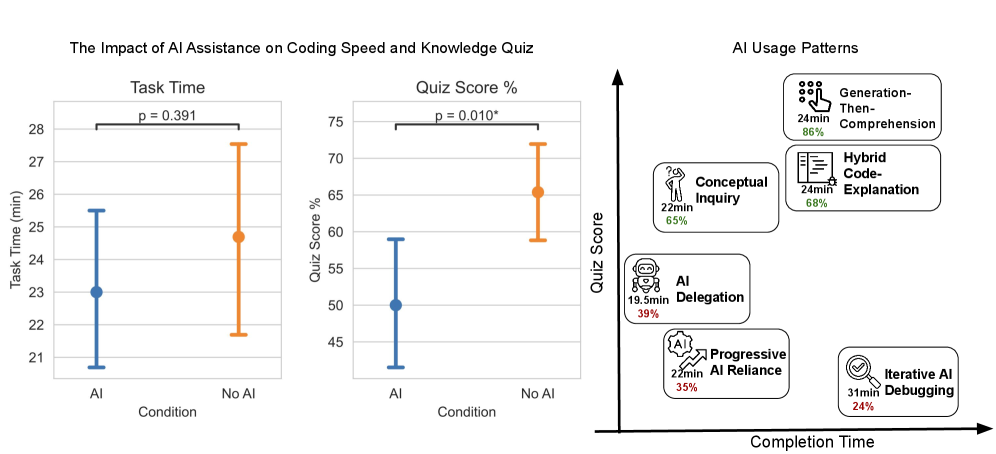

But here's where the paradox deepens. The productivity gains that motivated using AI in the first place didn't materialize consistently. Task completion time didn't improve significantly on average across the group. Some participants got faster with AI. Others didn't. Yet learning declined uniformly.

That should stop you. It's not like the classic productivity-learning tradeoff where you're sacrificing understanding for speed. The speed gains weren't reliable, but the understanding loss was.

When the researchers broke down the quiz results by question type, the largest gap appeared in debugging questions. This makes intuitive sense but carries serious implications. Debugging is the skill that separates someone who can execute given instructions from someone who can solve novel problems. It's what you need when things go wrong in ways nobody anticipated. It's the skill that creates actual safety margins in critical systems.

The most unsettling part of these results involved what participants believed about themselves. Those using AI reported higher enjoyment and felt like they were learning more. They perceived tasks as easier. Yet the quiz scores tell the opposite story.

Figure 9 shows self-reported enjoyment and learning by condition, with AI users reporting higher perceived learning despite actual knowledge losses

AI users felt like they were learning more despite learning measurably less.

Figure 10 shows self-reported task difficulty by condition, with AI users reporting lower difficulty throughout the study

Tasks felt easier with AI assistance, which itself becomes a problem.

This perception gap is dangerous. When learning feels effortless, you assume it's working. The interface creates a false signal of competence. You feel productive and capable precisely when you're building less understanding. This is the productivity mirage in its purest form: the system feels like it's working because it removes friction, but friction is often where learning happens.

Who suffers most

The story gets more complex when you look at experience levels. Not everyone paid the same price for using AI.

Figure 7 shows task completion time and quiz scores broken down by years of coding experience, with control group maintaining advantages across all levels

The learning penalty from AI assistance exists across experience levels, but novices suffer more.

Developers with more coding experience showed greater resilience to the learning deficit from AI. They maintained better quiz scores even when using AI. Those with less experience dropped further below the control group. The pattern is logical: experienced developers already have mental models of how programming works. They can integrate AI assistance into existing knowledge structures. Novices are still building the scaffolding itself, so skipping that construction process costs them more.

This creates an asymmetry that ought to concern anyone thinking about AI adoption at scale. Junior developers and career changers are statistically most likely to rely heavily on AI because it makes the learning curve feel manageable. It lets them complete tasks when they otherwise might struggle or ask for help. But they're also the group most vulnerable to compromised skill development. If you're early in your career and adopt heavy AI usage now, you're potentially sacrificing the foundational understanding that determines your ceiling later.

The implication extends beyond individuals. Organizations that onboard junior staff entirely with AI assistance might optimize for short-term productivity while creating a long-term competence problem. Workers who can execute but can't think independently don't scale well when problems become novel or complex.

When AI actually helps you learn

Here's where the research pivots from warning to opportunity. The paper's most important finding isn't that AI hurts learning. It's that whether AI helps or hurts depends entirely on how you interact with it.

The researchers identified six distinct patterns in how participants used the AI assistant. Three of those patterns preserved learning outcomes despite receiving AI assistance. The other three didn't.

Figure 11 shows six AI interaction personas with their average completion times and quiz scores

How you use AI matters more than whether you have access to it.

What distinguished the three high-learning patterns? Cognitive engagement. Participants who stayed actively involved in problem-solving even while using AI didn't suffer the learning penalty. Those who outsourced their thinking did.

The first pattern was verification seeking. These participants would work through a problem themselves, develop a solution or understanding, then ask the AI to check their work or validate their reasoning. This preserves learning because you're still building the mental model. The AI is a checkpoint, not a shortcut. You've already done the thinking, and the AI feedback either confirms your understanding or raises questions you then investigate.

The second pattern was question generation. Rather than asking the AI to solve a problem, these participants asked it to help them think through it. "Why might this be failing?" instead of "fix this code." They used AI as a thinking partner that could suggest hypotheses or directions to explore, but they remained the ones doing the actual reasoning. The friction stayed in the process.

The third pattern was debugging partnership. Participants would come to AI with a diagnosis problem: something's broken, help me understand why. They weren't asking for fixes, they were asking for collaborative reasoning. You'd suggest a hypothesis, AI would help you test it or suggest another angle. This kept the participant engaged in the problem-solving loop even when AI was present.

Compare these to passive patterns: asking AI to solve the entire problem then accepting the answer without reading it carefully, copying code without understanding it, treating AI as an oracle that generates solutions you implement without thinking. Those patterns showed the learning deficit. The difference wasn't tool access, it was cognitive engagement.

This transforms the research from "don't use AI for learning" (advice that's both unrealistic and wrong) to "use AI in ways that keep you thinking." It suggests the problem isn't AI itself, it's treating AI as a thought replacement rather than a thinking tool.

Designing workflows that preserve learning

The implications spread across three different groups, each with different leverage points.

For individuals learning new skills, the message is clear but requires discipline. Design your AI usage around engagement, not convenience. Before asking an AI for an answer, spend fifteen minutes struggling with the problem. If you're stuck, ask the AI to ask you questions rather than give you solutions. Use it to verify your thinking after you've done the thinking. This is slower than pure delegation, but it preserves the competence you're actually trying to build.

For organizations building training programs, this research creates an uncomfortable truth to face. Productivity gains in onboarding might come directly at the cost of worker competence. Especially in domains where safety depends on independent judgment, that's a dangerous bargain. Companies need to measure not just how quickly people get productive, but whether they can work independently once they do. The researchers note this matters most in safety-critical domains where problems routinely include edge cases and novel scenarios that no training regimen can fully cover.

For AI tool designers, there's an opportunity to shift defaults toward engagement. Could interfaces encourage the high-engagement interaction patterns? Imagine an AI assistant that refuses to simply generate code until you've explained what you're trying to do and why. Or one that always responds to problem-solving requests with diagnostic questions first. Or one that flags when you're passively consuming answers versus actively engaging. The current default interface makes passive consumption convenient and active engagement harder. Flipping that would be a small change with massive implications for learning outcomes.

The broader research question extends beyond programming. Does this pattern hold when doctors use AI diagnostic tools? When lawyers use legal research AI? When engineers use design assistance? Does more experienced practitioners show different effects? These questions point toward a research frontier that matters increasingly as AI becomes embedded in how work gets done.

The deeper pattern

This research ultimately challenges how we think about productivity and competence. Removing friction from work sounds unambiguously good until you realize that some friction is the mechanism of learning itself.

The struggle of debugging teaches you how systems work. The friction of reading unfamiliar code forces you to build mental models of programming patterns. The difficulty of solving novel problems from first principles builds the kind of flexible thinking that transfers to future problems you've never seen before.

This doesn't mean struggle is good in itself. Meaningless busywork isn't educational just because it's hard. But productive struggle, the kind where you're actively problem-solving and your confusion gets resolved through thinking, that's where deep learning happens. AI can wreck this by offering resolution without struggle. It can also protect it by staying engaged with the struggle rather than replacing it.

The most useful way to think about this: AI doesn't create a learning problem. It creates a design problem. Default AI usage patterns point toward passive consumption and outsourced thinking. That's the easier path, and easier paths get chosen. But the paper shows that engaged usage patterns are available. They require intentional interface design and intentional workflow choices, but they work.

Organizations and individuals need to ask harder questions about AI adoption than "does this make us faster?" The question that matters is "what are we trading away for that speed?" And then: "can we get the speed without the tradeoff?"

The encouraging part of this research is that the answer appears to be yes, but only if you're intentional about it. The dangerous part is that the default paths lead the wrong direction, and the mirage of productivity without learning is seductive precisely because it feels like it's working while it's quietly undermining it.