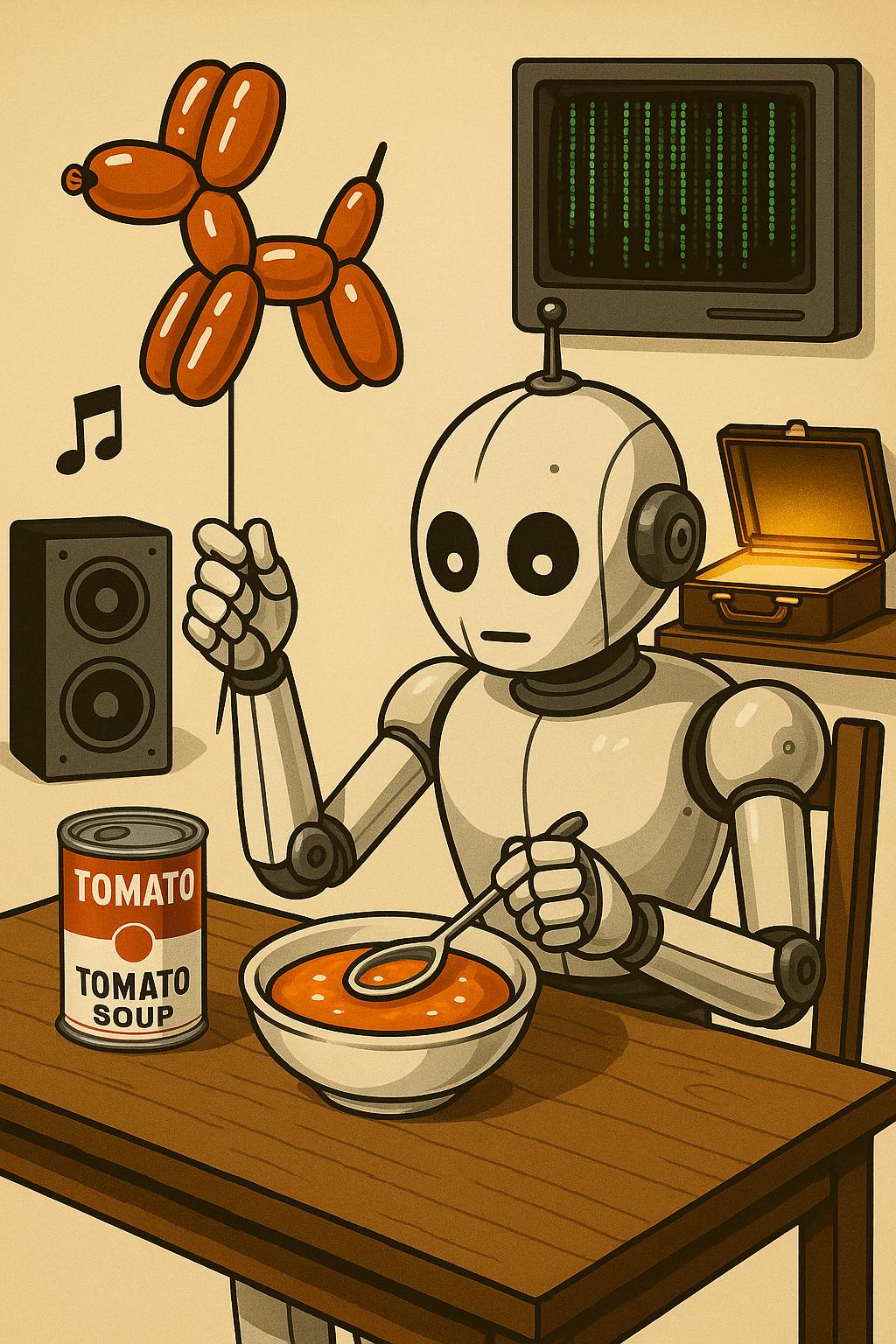

What do The Matrix, Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans, Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody, Jeff Koons’ Balloon Dog, and Pulp Fiction have in common? They all utilize the same postmodern concepts that underpin generative artificial intelligence, meaning AI operates as a coded, concentrated form of postmodernism.

OK, that was slightly hyperbolic, but truly, generative AI really rests on some heavy postmodern principles like simulacra and hyperreality, challenging authorship, pastiche, a mixing of high and low culture, and fragmented nonlinear methodology. So, let’s take a look at which postmodern feature underpins each of those pieces of art and how AI utilizes it in its operation.

One rather prominent feature of postmodernism is the idea of simulacra and hyperreality as proposed by French philosopher Jean Baudrillard (it’s so often the French when it comes to postmodernism). If you have no idea what I’m talking about, that’s probably ‘cause you lead a productive life, so let me explain.

A simulacrum is a representation or copy of something where a) the original is either lost or no longer relevant, or b) there never was an original. While it seems paradoxical on its face, it’s actually an accurate observation of postmodern phenomena.

Take the classic film The Matrix. What exactly is the Matrix besides a copy of a world that no longer exists? How many things in that world are not modeled after something real? Look at the agents, for example. It’s not like they’re a copy of some particular human–rather, they are a copy without an original. And while Baudrillard had some fundamental disagreements with the fact that the main characters could choose to be in a simulation or not, the film took much inspiration from him, as it is Baudrillard’s book on this exact topic that serves as a stash for Neo’s contraband.

Think about it: what else would you call a hyperrealistic photo of someone created primarily through prompt generation? When AI generates an image like this, there certainly is no direct referent. AI learns statistical patterns rather than distinct information, so its creation of a photorealistic image is a perfect example of a simulacrum.

And the thing with simulacra is that when the world becomes so full of them, the distinction between simulation and reality dissolves, with simulation taking over reality. That’s when we have entered the state of hyperreality. Turns out AI, due to its nature, is rather proficient at creating the conditions to enter hyperreality.

Oh, here’s something fun. Ever notice how when something wild is seen on social media now, half the commenters accuse the content of being AI-generated? Welcome to the beginning of hyperreality! So, that’s a rather apparent and now troubling operation of AI grounded in postmodernism. And to drive the final nail in the coffin, the existence of deepfakes kind of proves this point. So, there’s that… but there’s so much more underpinning postmodern art and AI!

One of the most influential series in postmodern art is Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans. In the early 1960s, Warhol produced a series of images that were replications of different varieties of Campbell’s soup. This also happened to be an extremely important move in postmodernism in terms of challenging authorship.

Warhol’s motives were immediately questioned, but it would become the next important piece to challenge authorship since the Dada movement’s urinal, better known as The Fountain, by Marcel Duchamp.

When Warhol, umm… appropriated the likeness of the cans, he was making a rather bold statement that has become a feature of postmodernism: challenging authorship.

Who, precisely, is the creator of Warhol’s can series? He certainly did not design any part of the can, so is the image his? And let’s be clear: in no manner was he trying to alter the visual qualities of the soup can. He was trying to reproduce it. That Campbell’s considered suing him only heightens this as a feature of postmodernism.

And guess what anyone can do today? They can have a generative AI create an infinite number of distinct Campbell’s soup cans. But of course, this raises the question as to where the authorship lies. Is it the person or team who designed the can and logo for Campbell’s? What about the AI that produced the image? Well, it certainly wouldn’t have been produced without a user’s explicit instruction. So again, where precisely does authorship lie?

When van Gogh painted The Starry Night, there was never any question as to who the artist was. When you have your AI re-interpret that painting, who precisely becomes the artist? If you have the answer to that, I assume you are unable to talk about it because you have ascended into a higher realm of understanding. And congrats to you! But the rest of us are gonna be left here scratching our heads as to who can claim authorship. Plus, when you get so many disparate things coming together in a unifying force, you’re bound to get pastiche.

Is this the real life

Is this just fantasy

Caught in a landslide

No escape from hyperreality

OK, I might have put my personal touch on the last word there, but it certainly still rings true. In any case, this ridiculously famous song is a wonderful example of pastiche in postmodern art. Pastiche is when you take from different sources in order to make something new, and it pops up quite frequently in postmodern art.

As for Bohemian Rhapsody, what is the exact genre that the song falls into? Well, it relies heavily on rock ‘n’ roll, opera, and ballad. And for much of the song, it’s not a fusion of music because each genre is easily identified. It’s not transforming any of the genres; instead, it is recycling parts from each to create an assemblage. And this leads us to a key feature of postmodern pastiche: the absence of critical intent.

And guess what? Take the operatic portion of the song. A lot of the lyrics in that portion are nonsensical, and it’s clearly not an opera, but it’s a reference to an opera. Of course, it’s not an opera as it’s missing many of the key elements, such as a grand narrative. So in a way, it’s actually a simulacrum of an opera. The musical sign for opera has replaced opera itself, and naturally, it lacks critical intent.

I bet you never considered that part of the song! Don’t worry; it doesn’t ruin the song in any manner.

As for pastiche and AI, AI is simply doing what Queen did. Queen assembled elements from different musical genres and produced an ever-popular song. AI assembles patterns learned across different sources to generate a coherent response, whether textual, visual, or auditory. AI is doing postmodern pastiche in the perfect way: with an absence of critical intent. It happens to do this in a manner that is also postmodern: with the mixing of high and low culture.

Imagine going to a circus and getting a balloon dog. If I forced you into a binary of considering the balloon dog a part of high or low culture, you’re going with low every time.

Now, imagine taking that same balloon dog and elevating it culturally, say by making it out of precision stainless steel, claiming it’s fine art, and putting it up for sale and receiving millions of dollars. If you ever wonder what that might feel like, just ask Jeff Koons. He did exactly that starting in the ‘90s and has made quite the name for himself as a postmodern artist in large part because of that series of art. His art also firmly entrenched the notion that one aspect of postmodern art involves the mixing of high and low culture.

For musical examples, look no further than hip-hop or heavy metal that incorporates elements from the symphony; Xzibit and Metallica come to mind. Xzibit often used symphonic samples (a postmodernist could easily argue symphonic simulacra), and Metallica’s S & M album (Symphony and Metallica) is a wonderful demonstration of this point.

Generative AI happens to be a master at this. Think about all the different pieces of information that went into training generative AI. If it’s an LLM, it’s been trained on the works of Shakespeare, top academic theorists, and Reddit forums. A popular news story that happened in 2024 perfectly illustrates this point.

Someone typed in a Google search, “cheese not sticking to pizza.” Google’s AI Overview first recommended a culinary solution that requires knowledge of cooking, while the second solution suggested adding a ⅛ cup of nontoxic glue to the sauce.

It seems the AI’s brilliant recommendation to add glue to pizza was drawn from a supposed 11-year-old comment on Reddit. That it seemed to use high culture for the first suggestion and low culture for the second suggestion in a single answer is demonstrative of the culture-mixing power of AI. That it gave equal weight to both forms of culture, besides being shocking, is entirely postmodern. The last phenomenon, a fragmented nonlinear narrative, is also decidedly postmodern.

Pulp Fiction was released in 1994, and it became so popular that it was nominated for seven Oscars and won Best Original Screenplay, amongst many other accolades from a variety of organizations. This film was and remains quite popular.

And what made it so endearing with viewers and critics alike? Well, it would be rather challenging to argue its postmodern qualities, particularly its fragmented, nonlinear story, a popular technique in postmodern narration, didn’t play an important part in its success. And funnily enough, AI generates its responses in a way that functionally parallels Tarantino’s fragmented nonlinearity — through nonlinear, token-by-token prediction rather than any prewritten linear narrative.

While the outputs are certainly different, the way they come together is analogous: both unfold through the assembly of non-sequential fragments.

Just as Tarantino surprised viewers by creating a story in a fragmented, nonlinear fashion, AI generates outputs through an analogous form of fragmented nonlinearity. When you ask an LLM a question, it’s not giving you some preconceived, coherent response. What it’s actually doing is predicting the next token or smallest meaningful textual unit, such as a word or punctuation. It’s also basing its response recursively off of what’s been said before, in addition to following algorithmic weights. To sum up, AI generates its responses by assembling them token by token through probability rather than by following any prewritten linear path, acting as a computational parallel to Tarantino’s narrative fragmentation.

And just to preempt the inevitable whining, remember, Barthes’ The Death of the Author reminds us to not infer an artist's intent, and even more, that the artist’s intent is irrelevant, which is perfect as AI has no intent. Plus, in addition to challenging authorship, Duchamp’s The Fountain likewise challenged intent over 100 years ago.

So, if generative AI creates simulacra and places us in the perfect position to enter hyperreality, challenges authorship, utilizes pastiche, mixes high and low culture, and uses fragmentation and nonlinearity to generate outputs, that leaves us in a rather interesting pickle. I am a firm believer in the “if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck” notion. So, if it walks like postmodernism and talks like postmodernism, am I to believe it’s a piece of cheddar?

Yes, it does achieve its methods through math and computation while humans do it through thought, but if the effect is the same nonetheless, are we still going to persist in claiming AI is decidedly not postmodern?

And with deepfakes no longer being relegated to highly skilled Photoshop editors but now available to anyone with the ability to type, that certainly suggests something about the current state of postmodernism. If a machine that functions as coded postmodernism can put us as a society into the conditions to enter hyperreality and essentially automate postmodernism, to me at least, that puts us squarely in the postmodern cultural epoch, despite the calls and hopes that we may have moved past it.

Yay.