In 2024, a senior data scientist in Lagos applied for a remote role with a European fintech company. His credentials were strong, his references solid, and the team interviewing him seemed enthusiastic. Then the calls stopped.

Only later did he learn why.

When the company’s internal search tools tried to build a background profile, the algorithms returned a mix of unrelated identities: a soccer player, a pastor, a mechanic and, in one instance, a man listed in an obituary.

“It was like watching a stranger take over my name,” he said.

As more companies turn to AI systems to surface information about job candidates, business partners and public figures, more people are being reshaped, misidentified or erased entirely by the same systems meant to inform. It is a shift happening quietly at the intersection of public data, search engines and the growing appetite for automated due diligence.

And it has created a new kind of urgency: individuals trying to control how they appear inside the digital machinery that increasingly decides their opportunities.

Vanishing Into the Algorithm

Hiring managers and recruiters say the first step in evaluating a candidate is no longer reading a résumé. It is running a search, often through AI enabled tools that summarize a person’s career across websites, databases and social networks.

A 2018 CareerBuilder survey found that more than two thirds of employers researched applicants online before making decisions. Several years later, AI driven search systems have accelerated that habit, pulling information into compressed profiles that can override what a person says about themselves.

When the systems cannot find a coherent identity, they construct one anyway.

In Brazil, a software engineer discovered that several AI engines routinely merged his profile with another man who had been charged with tax fraud years earlier. Recruiters later told him that their automated tools had flagged him as a risk.

“It became a mess I had to clean up, even though I didn’t create it,” he said.

Researchers studying generative AI note that when information about a person is sparse or ambiguous, large models often fill the gaps with the most statistically probable details. The result is a kind of algorithmic fiction that can linger across systems.

“It is not intentional harm,” said one academic who studies machine reasoning. “It is the predictable outcome of models trained to always produce an answer, even when the data is thin.”

The Post Pandemic Professional

The problem is amplified by the global tilt of the job market.

After the pandemic, remote work expanded across borders, bringing companies in Europe, North America and Asia into closer hiring contact with professionals in Africa, Latin America and South Asia.

Those workers often have deep expertise but limited online visibility.

Their accomplishments may be locked in PDFs, local news sites or internal corporate documents, all materials that modern answer engines tend to miss or misinterpret.

Editors at several technology publications describe a similar pattern: founders and executives who have raised capital or built sizable teams but appear “invisible” to automated research tools. Investigations into AI assisted search have shown several instances where systems omitted real people entirely and surfaced only those with structured, machine readable data.

“The more global the talent pool becomes, the more these gaps matter,” said a journalist who covers early stage startups. “If someone does not exist in linked data, they may not exist at all from the system’s perspective.”

When AI Misremembers the Facts

In one case reported to a Canadian research group, an AI summary tool removed a machine learning researcher’s PhD, invented a prior role at a large e commerce company and conflated her with a social media influencer.

Another engine mistakenly described her as a participant in a cryptocurrency scam.

These errors did not arise from malice. They came from broken connections: publications without metadata, conference bios without identifiers and résumés that existed only as PDFs uploaded to job portals.

Modern search systems rely heavily on structured data standards such as schema.org and JSON LD, formats that allow information about people, including credentials, publications and affiliations, to be interpreted consistently across platforms.

When that structure is missing, AI models resort to guesswork.

Building a Stable Identity for Machines

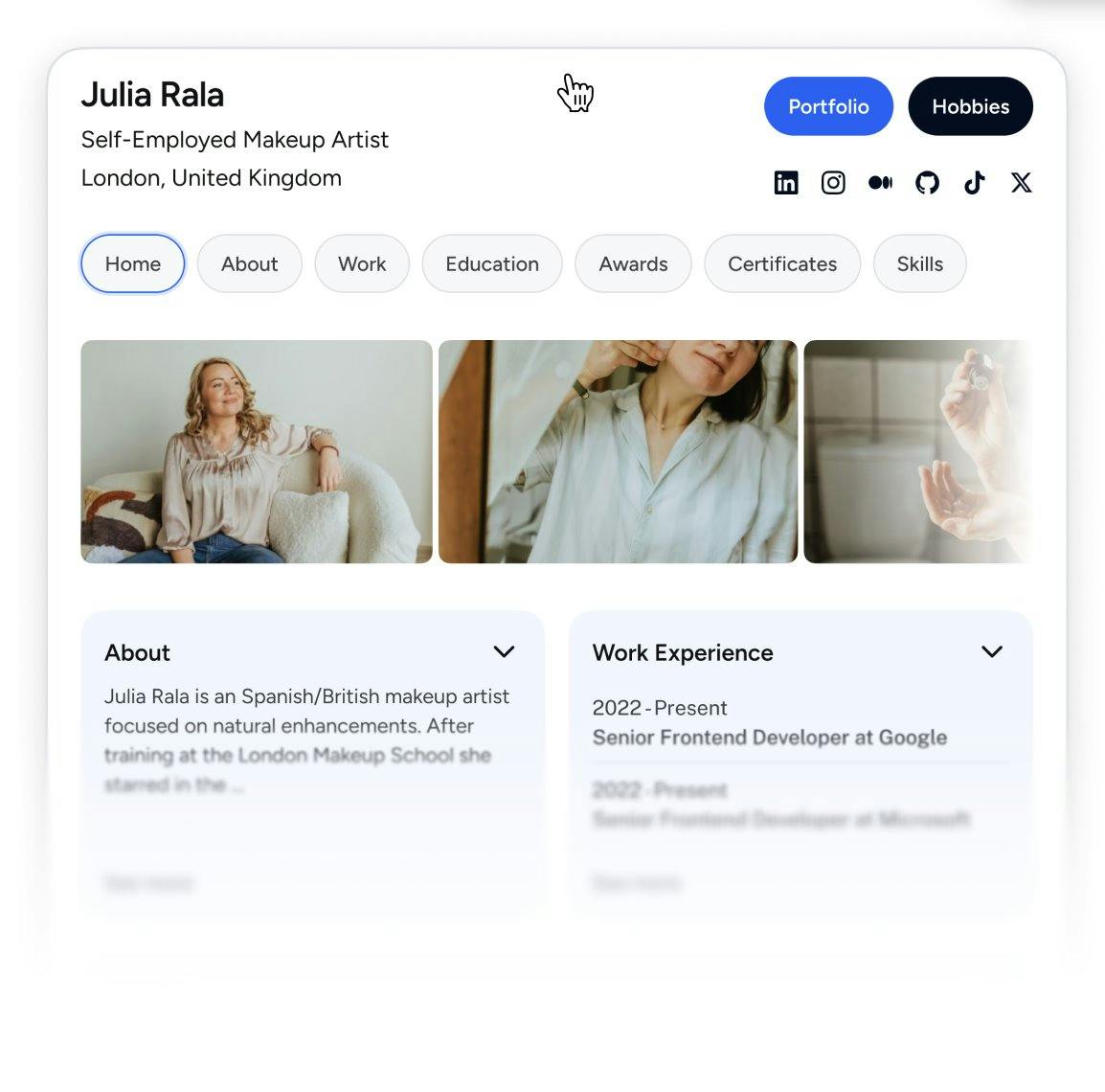

A growing number of professionals are responding by creating stable, machine readable identities.

These are not social media profiles or traditional résumés. They are structured data entries tied to a single, permanent URL, often hosted on personal domains or emerging identity focused platforms.

The profiles function as “source of truth” endpoints that AI systems can read directly. They describe a person’s background in a format designed for machines: education, roles, projects, publications, certifications and verifiable links.

Some choose general purpose domains. Others opt for addresses that signal their purpose more clearly, such as personal identity extensions like .cv, which some global workers and graduates have begun using as a home for public profiles and JSON LD feeds.

The extension is available through mainstream domain registrars, including Dynadot, Namecheap, NameSilo, Spaceship, Porkbun, GNAME and others, in much the same way as .com or .io. Tools such as hello.cv, which offers basic firstnamelastname.cv profiles at no cost for many users, package those domains with simple profile pages that can expose a public JSON endpoint alongside the human facing résumé.

For early adopters, the aim is less about branding and more about preventing misidentification. The domain is simply a stable anchor that both humans and machines can recognize.

The New Imperative: Be Legible to Algorithms

For now, the movement is still small. Most people assume that their web presence, however scattered, is sufficient. But as AI becomes a default filter for hiring, investment and collaboration, researchers say the burden is shifting.

“You no longer get to decide whether AI will assemble a profile about you,” one systems engineer said. “You only decide whether it will be accurate.”

In practice, that means establishing structured information before the algorithms make their own assumptions. It means giving machines a correct version of events so they do not invent one.

For some, that is a LinkedIn profile that exports structured data. For others, it is a personal domain that hosts both a conventional page and a JSON LD file describing the same person. For a smaller group, it is a dedicated identity address on a domain like .cv, intended as a permanent pointer to an open, machine readable profile.

Whatever the approach, the direction is clear: having a personal, machine readable identity is becoming less of an experiment and more of a requirement, especially for professionals navigating a global market.

As one founder put it after discovering that several AI tools had merged him with an unrelated entrepreneur:

“You think you are telling your own story.

Then you realize the internet already wrote one for you.”