We often picture the race for dominance in artificial intelligence as a contest of algorithms and data. But what if the real story has less to do with code and more to do with concrete?

This isn’t just a metaphor. In 2024 and 2025, some of the most ambitious AI initiatives were held up not because the models weren’t ready, but because they couldn’t get online. Power shortages, overloaded grid queues, and delays in permitting caused setbacks more than any lack of intelligence.

In practice, it showed up in mundane and frustrating ways: teams stuck in permitting queues, data centers negotiating for limited electricity, and compute access that looked good on paper, but didn’t arrive when it was needed.

This guide isn’t here to rank models. Instead, it maps out the infrastructure and governance pressure points that increasingly define what AI can actually do in the world. The focus is on scaling, stability, and the systems that support both.

What This Essay Is (and Isn’t)

This is a public-facing field map. It doesn’t try to build a formal theory, test hypotheses, or offer complete coverage. Instead, the goal is to help technologists, policy analysts, and internationally minded readers identify recurring patterns—where AI capability depends on physical systems and governance frameworks that can be stressed, monitored, or redesigned.

Scope Note: The Geopolitics of AI Spans Multiple Layers

At the upstream level, access to materials like critical minerals and rare earths shapes hardware supply chains and remains geopolitically significant.

A second layer concerns industrial capacity—semiconductor manufacturing, fabrication bottlenecks, and the export controls that govern who can produce advanced chips.

This essay focuses on a third, downstream layer: the infrastructures and governance arrangements through which AI capability is actually scaled, deployed, and made operational. These include electricity access, grid connectivity, compliance systems, platform environments, and organizational capacity.

That choice is deliberate, and it matters. While upstream resources and industrial production matter, many of today’s real constraints—and much of the emerging leverage—show up downstream, where systems are powered, connected, governed, and used.

The upstream and midstream dynamics of AI geopolitics are crucial and will be explored separately in dedicated essays.

1. The Real Mistake: Thinking It’s Just About the Models

A lot of AI geopolitics gets narrated like a sports table: who has the most capable model, who is ahead in benchmarks, who is winning the “race.” That view misses the layer that often decides whether AI becomes strategically consequential: scaling and deployment.

Frontier AI is increasingly an infrastructure-bound capability. It scales only through controlled access to compute, reliable power, resilient connectivity, and platforms that mediate deployment. These kinds of dependencies often turn into leverage points that look less like “better code” and more like who can govern access, reliability, and rules of use.

Why do questions of access, scaling, and deployment conditions attract such political attention? One reason is the sheer scale of the potential economic upside.

Source: McKinsey Global Institute (2023), The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier (Exhibit 2)

McKinsey’s latest research estimates that generative AI alone could add $2.6 trillion to $4.4 trillion annually in economic value across 63 use cases—roughly comparable to the entire GDP of the United Kingdom in 2021 ($3.1 trillion).

At that scale, generative AI would increase the overall impact of artificial intelligence by 15 to 40 percent, helping explain why questions of scaling, access, and governance rapidly become political rather than purely technical.

2) A Different Lens: From Models to Scaling Conditions

Here’s a more useful question than “who has the best model?”:

Who can reliably build, run, and operationalize AI at scale — and under what constraints?

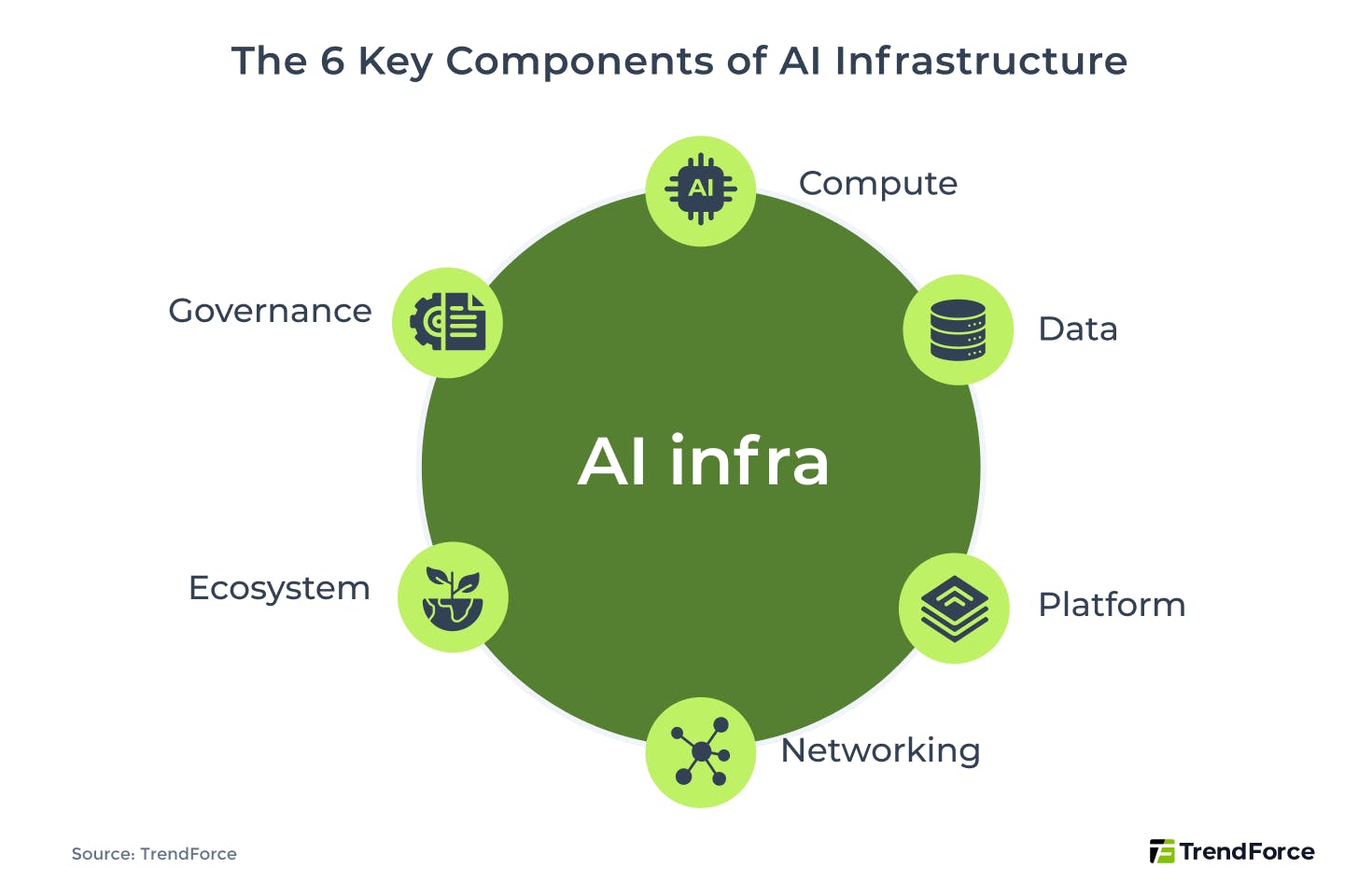

This lens makes some topics suddenly central:

- Energy and grid throughput (can the new load connect fast enough?)

- Compute supply and export controls (who can access cutting-edge chips and systems?)

- Physical connectivity (routes, landing points, repair capacity)

- Organizational integration (can institutions field AI safely, securely, and at speed?)

- Platform governance (who sets the practical rules through APIs, compliance, and audit tooling?)

This is not a claim that these factors determine outcomes mechanically. It is a map of where conditions and constraints repeatedly surface in current debates.

What makes these constraints easy to miss is that they sit outside the usual narratives of innovation. They are slow, procedural, and physical—often invisible until they suddenly become binding.

3) A Simple Map: Three Recurring “Faces” of Power in AI Systems

To keep things concrete, think of AI power showing up in three recurring ways:

- Access leverage: Where the ability to scale depends on scarce inputs or slow-to-substitute systems, access can be conditioned through policy, licensing, procurement, or allocation. This kind of leverage is visible when access depends not on market price, but on licensing decisions, capacity allocation, or regulatory approval.

- Visibility leverage - Power isn’t only denial; it can also be visibility: the capacity to observe, audit, attribute, and shape behavior through standards, monitoring, and compliance architectures. Here, power comes less from blocking access and more from knowing who is doing what, where, and under which constraints.

- Architecture leverage: Beyond access and visibility lies the ability to shape the field by setting default rules: interoperability standards, procurement templates, audit expectations, and platform constraints that raise switching costs and privilege certain ecosystems. Over time, these design choices quietly shape what kinds of AI systems are easy to build—and which ones become prohibitively costly.

This is a heuristic meant to make recurring patterns easier to see, not to define analytical categories or offer a complete framework.

4) The Infrastructural Pressure Points That Keep Reappearing

The same lesson shows up again when you zoom out: AI scaling runs into constraints. Forecasts from Epoch AI suggest that by 2030, training-scale growth could be limited by power, chip supply, data quality, or latency. These aren’t theoretical limits.

We’re already seeing them in action.

Source: Epoch AI, “Can AI scaling continue through 2030?”

Compute is a good example. Advanced models depend on cutting-edge chips, often sourced from a small number of countries and suppliers. This level of concentration leaves AI development exposed to export controls, chokepoints, and shifting geopolitical winds, as outlined by the U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security and CSET in 2023.

Linked closely to compute is a more basic issue: power. The International Energy Agency (IEA) and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) have both shown that the ability to scale AI depends heavily on whether data centers can secure stable electricity and connect to the grid without delay. In many cases, energy access is now the most immediate limiter.

Connectivity is another overlooked constraint. Undersea cables move the vast majority of global internet traffic. Their routes, landing stations, and redundancy systems shape cloud performance and cross-border capacity. As noted by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), these cables are increasingly recognized as critical infrastructure.

Even when the technology is available, organizational capacity can determine whether it delivers strategic value. NATO’s 2024 AI strategy points out how varied institutions are in their ability to integrate AI into procurement, security, and operations.

Then there’s the data and sensor layer. Strategic AI doesn’t always rely on public training sets. It often depends on specific, time-sensitive data—collected through sensors, fused, labeled, and deployed in tightly integrated pipelines.

Finally, AI capability often flows through platform environments—cloud services, APIs, compliance layers, and monitoring systems. Governance frameworks like the EU AI Act (2024) and NIST’s AI Risk Management Framework don’t just shape ethical use. They influence which systems can be launched and scaled—and which get blocked by design.

When taken together, these dependencies show that AI competition increasingly hinges on infrastructure timelines, supply constraints, and institutional readiness, not just raw innovation speed.

5. Why This Matters for How We Talk About AI Geopolitics

When we look at AI through the lens of infrastructure, the conversation shifts in important ways.

First, power becomes infrastructural. Advantage is no longer just about building the most advanced model or leading in benchmarks. What increasingly matters is the ability to scale, deploy, and sustain those systems under real-world constraints such as electricity, compute supply, connectivity, and compliance conditions. Technical innovation still matters, but it cannot succeed on its own.

Second, governance becomes a form of strategic influence. Rules, standards, and compliance mechanisms do not simply manage risk or ensure responsible use. They shape behavior at scale. They determine what can be deployed, who gets access, and under which conditions systems operate.

Third, resilience becomes part of grand strategy. Infrastructure that once lived in the background—grids, cables, data centers, platforms—now affects national security and international coordination. Delays in permitting or slow grid approvals may look technical, but they increasingly shape outcomes. They are emerging as strategic vulnerabilities.

That said, these pressure points do not automatically determine outcomes. Systems can be reconfigured. Dependencies can shift. And the effectiveness of governance depends on political dynamics, institutional capacity, and coordination across allies.

Even so, the direction is clear. The geopolitics of AI is moving downstream. The focus can no longer be limited to technical capability. It must include the infrastructures and governance systems that shape how AI becomes real in the world.

6. Open Questions: Where the Next Debate Should Go

If AI capability increasingly depends on infrastructure and governance, then future discussions need to ask a different set of questions.

Which dependencies are likely to harden into long-term strategic constraints, and which ones might fade or evolve with time? Not every bottleneck lasts forever, and not every chokepoint becomes permanent. Some may be resolved through innovation, others through political shifts or market realignments.

How can alliances coordinate on standards and build resilience without fragmenting the very systems they rely on? Greater control can strengthen sovereignty and security, but it can also lead to incompatible rules and lost interoperability. Finding the right balance will be critical.

What trade-offs will emerge between resilience, control, innovation, and openness? Increasing oversight can protect critical systems, but it might also slow down adoption or raise the cost of collaboration. How much centralization is too much, and how much openness is too risky?

For governments, the challenge will be managing these tensions. Tighter control over AI infrastructure may improve national resilience. But it may also raise barriers to innovation and complicate international cooperation.

Ultimately, it may not come down to who builds the best model but to who governs the systems that models rely on.

Disclosure

This essay is written for a general audience. A substantially different academic article, with a narrower research question, formal conceptual framework, and systematic evidence, is under development.

-

References (Author–Date)

Epoch AI. 2024. “Can AI scaling continue through 2030?” https://epochai.org/blog/can-ai-scaling-continue-through-2030

McKinsey Global Institute. 2023. The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier.

Landing:https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/tech-and-ai/our-insights/the-economic-potential-of-generative-ai-the-next-productivity-frontier

PDF:https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/mckinsey%20digital/our%20insights/the%20economic%20potential%20of%20generative%20ai%20the%20next%20productivity%20frontier/the-economic-potential-of-generative-ai-the-next-productivity-frontier.pdfInternational Energy Agency. 2025. “Energy Supply for AI.” https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-and-ai/energy-supply-for-ai

Shehabi, Arman, et al. 2024. 2024 United States Data Center Energy Usage Report. LBNL. https://eta-publications.lbl.gov/sites/default/files/2024-12/lbnl-2024-united-states-data-center-energy-usage-report_1.pdf

International Telecommunication Union. 2024. “Submarine Cable Resilience.” https://www.itu.int/en/mediacentre/backgrounders/Pages/submarine-cable-resilience.aspx

NATO. 2024. “Summary of NATO’s Revised Artificial Intelligence (AI) Strategy.” https://www.nato.int/en/about-us/official-texts-and-resources/official-texts/2024/07/10/summary-of-natos-revised-artificial-intelligence-ai-strategy

U.S. Department of Energy. 2024. “DOE Releases New Report Evaluating Increase in Electricity Demand from Data Centers.” https://www.energy.gov/articles/doe-releases-new-report-evaluating-increase-electricity-demand-data-centers

U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security. 2023. Export controls page on advanced computing/semiconductors. https://www.bis.gov/press-release/bis-updated-public-information-page-export-controls-imposed-advanced-computing-semiconductor

Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET). 2023. “The Commerce Department’s October 2023 Export Control Update: An Explainer.” https://cset.georgetown.edu/article/bis-2023-update-explainer/

National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2023. AI Risk Management Framework 1.0. https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/NIST.AI.100-1.pdf

European Union. 2024. Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 (AI Act). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj/eng