ANDREA BARTZ, CHARLES GRAEBER, and KIRK WALLACE JOHNSON v. ANTHROPIC PBC, retrieved on June 25, 2025, is part of

Statement

Defendant Anthropic PBC is an AI software firm founded by former OpenAI employees in January 2021. Its core offering is an AI software service called Claude. When a user prompts Claude with text, Claude quickly responds with text — mimicking human reading and writing. Claude can do so because Anthropic trained Claude — or rather trained large language models or LLMs underlying various versions of Claude — using books and other texts selected from a central library Anthropic had assembled. Claude was first released publicly in March 2023. Seven successive versions of Claude have been released since. Users may ask Claude some questions for free. Demanding users and corporate clients pay to use Claude, generating over one billion dollars in annual revenue (Opp. Exh. 18).

Plaintiffs Andrea Bartz, Charles Graeber, and Kirk Wallace Johnson are authors of books that Anthropic copied from pirated and purchased sources. Anthropic assembled these copies into a central library of its own, copied further various sets and subsets of those library copies to include in various “data mixes,” and used these mixes to train various LLMs. Anthropic kept the library copies in place as a permanent, general-purpose resource even after deciding it would not use certain copies to train LLMs or would never use them again to do so. All of Anthropic’s copying was without plaintiffs’ authorization.

Author Bartz wrote four novels Anthropic copied and used: The Lost Night: A Novel, The Herd, We Were Never Here, and The Spare Room. Author Graeber wrote two non-fiction books likewise at issue: The Good Nurse: A True Story of Medicine, Madness, and Murder, and The Breakthrough: Immunotherapy and the Race to Cure Cancer. And, Author Johnson penned three non-fiction books also copied and used: To Be A Friend Is Fatal: The Fight to Save the Iraqis America Left Behind, The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century, and The Fishermen and the Dragon: Fear, Greed, and a Fight for Justice on the Gulf Coast. Plaintiffs Bartz Inc. and MJ + KJ Inc. are corporate entities that Author Bartz and Author Johnson respectively set up to market their works. Between them, these five plaintiffs (“Authors”) own all the copyrights in the above-listed works.

From the start, Anthropic “ha[d] many places from which” it could have purchased books, but it preferred to steal them to avoid “legal/practice/business slog,” as cofounder and chief executive officer Dario Amodei put it (see Opp. Exh. 27). So, in January or February 2021, another Anthropic cofounder, Ben Mann, downloaded Books3, an online library of 196,640 books that he knew had been assembled from unauthorized copies of copyrighted books — that is, pirated. Anthropic’s next pirated acquisitions involved downloading distributed, reshared copies of other pirate libraries. In June 2021, Mann downloaded in this way at least five million copies of books from Library Genesis, or LibGen, which he knew had been pirated. And, in July 2022, Anthropic likewise downloaded at least two million copies of books from the Pirate Library Mirror, or PiLiMi, which Anthropic knew had been pirated (Opp. Exh. 6 at 4; Opp. Expert Zhao ¶¶ 17–29; see Class Cert. (“CC”) Opp. Expert Iyyer ¶¶ 45–46). Although what was downloaded and later duplicated from these sources was sometimes referred to as data or datasets, at bottom they contained full-text “ebooks or scans of books” saved in individual files in formats like .pdf, .txt, and .epub (see, e.g., Opp. Exh. 12 at - 0391318). For Books3, most filenames identified the book inside. For LibGen and PiLiMi, Anthropic downloaded a separate catalog of bibliographic metadata for each collection, with fields like title, author, and ISBN (see, e.g., ibid.; Opp. Exh. 16 -0533972–73). Anthropic thereby pirated over seven million copies of books, including copies of at least two works at issue for each Author. (1)

As Anthropic trained successive LLMs, it became convinced that using books was the most cost-effective means to achieve a world-class LLM. During this time, however, Anthropic became “not so gung ho about” training on pirated books “for legal reasons” (Opp. Exh. 19). It kept them anyway (e.g., Opp. Exh. 17 at 93–94; CC Opp. Exh. 35 at -0273474). To find a new way to get books, in February 2024, Anthropic hired the former head of partnerships for Google’s book-scanning project, Tom Turvey. He was tasked with obtaining “all the books in the world” while still avoiding as much “legal/practice/business slog” as possible (Opp. Exhs. 21, 27). So, in spring 2024, Turvey sent an email or two to major publishers to inquire into licensing books for training AI. Had Turvey kept up those conversations, he might have reached agreements to license copies for AI training from publishers — just as another major technology company soon did with one major publisher (e.g., Opp. Expert Malackowski ¶¶ 50, 64). But Turvey let those conversations wither.

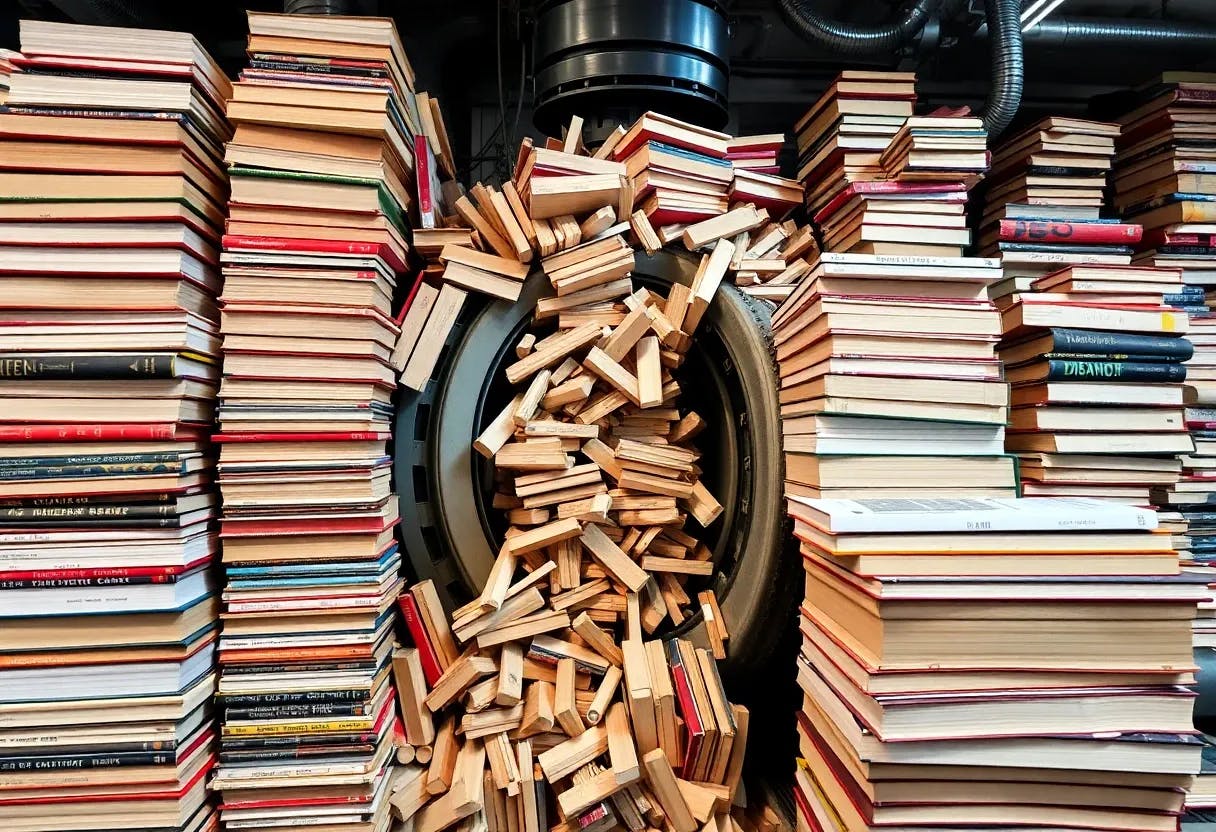

Instead, Turvey and his team emailed major book distributors and retailers about bulkpurchasing their print copies for the AI firm’s “research library” (Opp. Exh. 22 at 145; Opp. Exh. 31 at -035589). Anthropic spent many millions of dollars to purchase millions of print books, often in used condition. Then, its service providers stripped the books from their bindings, cut their pages to size, and scanned the books into digital form — discarding the paper originals. Each print book resulted in a PDF copy containing images of the scanned pages with machine-readable text (including front and back cover scans for softcover books).

Anthropic created its own catalog of bibliographic metadata for the books it was acquiring. It acquired copies of millions of books, including of all works at issue for all Authors. (2)

Anthropic may have copied portions of Authors’ books on other occasions, too — such as while copying book reviews, academic papers, internet blogposts, or the like for its central library. And, Anthropic’s scanning service providers may have copied Authors’ print books along the way to delivering the final digital copies to Anthropic. But neither side here specifically raises legal issues implicated by any such copies. Nor will this order.

From all the above sources, Anthropic created a general “research library” or “generalized data area.” What was this for? As Turvey said, this was a “way of creating information that would be voluminous and that we would use for research,” or otherwise to “inform our — our products” (Opp. Exh. 22 at 145–46, 194). The copies were kept in the original “version of the underlying” book files Anthropic had “obtained or created,” that is, pirated or scanned (Opp. Exh. 30 at 3, 4). Anthropic planned to “store everything forever; we might separate out books into categories[, but t]here [wa]s no compelling reason to delete a book” — even if not used for training LLMs.

Over time, Anthropic invested in building more tools for searching its “general purpose” library and for accessing books or sets of books for further uses (see CC Br. Exh. 12 at -0144509; CC Reply Exh. 45 at -0365931–32, -0365939– 42 (reviewing and seeking to improve “[w]hat [ ] researchers do today if they want to search for a book,” including improving bibliographic metadata and consolidating varied resources)).

One further use was training LLMs. As a preliminary step towards training, engineers browsed books and bibliographic metadata to learn what languages the books were written in, what subjects they concerned, whether they were by famous authors or not, and so on — sometimes by “open[ing] any of the books” and sometimes using software. From the library copies, engineers copied the sets or subsets of books they believed best for training and “iterate[d]” on those selections over time. For instance, two different subsets of print-sourced books were included in “data mixes” for training two different LLMs. Each was just a fraction of all the print-sourced books. Similarly, different sets or “subsets” or “parts of” or “portions” of the collections sourced from Books3, LibGen, and PiLiMi were used to train different LLMs. Anthropic analyzed the consequences of using more books, fewer books, different books. The goal was to improve the “data mix“ to improve each LLM and, ultimately, Claude’s performance for paying customers. (3)

Over time, Anthropic came to value most highly for its data mixes books like the ones Authors had written, and it valued them because of the creative expressions they contained. Claude’s customers wanted Claude to write as accurately and as compellingly as Authors. So, it was best to train the LLMs underlying Claude on works just like the ones Authors had written, with well-curated facts, well-organized analyses, and captivating fictional narratives — above all with “good writing” of the kind “an editor would approve of” (Opp. Exh. 3 at -03433). Anthropic could have trained its LLMs without using such books or any books at all. That would have required spending more on, say, staff writers to create competing exemplars of good writing, engineers to revise bad exemplars into better ones, energy bills to power more rounds of training and fine-tuning, and so on. Having canonical texts to draw upon helped (e.g., Opp. Expert Zhao ¶ 81).

(1) Specifically, those works were (see Opp. Expert Zhao ¶ 36; CC Br. Expert Zhao ¶ 66):

- Author Bartz’s The Herd (five copies total) (in LibGen and PiLiMi);

- Author Bartz’s The Lost Night (three copies total) (in Books3, LibGen, and PiLiMi);

- Author Graeber’s The Breakthrough (four copies) (in Books3, LibGen, and PiLiMi);

- Author Graeber’s The Good Nurse (five copies total) (in Books3 and LibGen);

- Author Johnson’s To Be A Friend Is Fatal (one copy) (in Books3); and

- Author Johnson’s The Feather Thief (four copies total) (in Books3, LibGen, PiLiMi).

Some evidence suggests Anthropic downloaded still more copies before culling empty files, duplicates, and so on to reach the numbers kept in the central library and counted here.

(2) In other words, within the scanned books were one or more copies of the following works:

- Author Bartz’s The Herd;

- Author Bartz’s The Lost Night;

- Author Bartz’s We Were Never Here;

- Author Bartz’s The Spare Room;

- Author Graeber’s The Breakthrough;

- Author Graeber’s The Good Nurse;

- Author Johnson’s To Be A Friend Is Fatal;

- Author Johnson’s The Feather Thief; and,

- Author Johnson’s The Fishermen.

(3) (See, e.g., Opp. Exh. 12 at -0391318 (engineers were able to “open any of the books”); CC Reply Exh. 45 at -0365941 (some engineers “want[ed] to search for a book” and get its “scanned book file[ ]”); Opp. Exh. 30 at 3 (made copies of “each such dataset or portions thereof” for training); Opp. Exh. 6 at 3–4 (trained on “portions of datasets,” with at least two such portions from LibGen and four from PiLiMi); Opp. Expert Zhao ¶¶ 27–28, 30–31 (plus two more from PiLiMi, and at least three from scanned books); CC Opp. Exh. 35 at -0273477–82 (tested subsets of pirated and purchased-and-scanned books to see consequences for training); CC Br. Exh. 12 at - 0144508–09 (“iterate[d]” selections from library and “train[ed] new models on the best data”); Br. Expert Kaplan ¶¶ 42–45 (explained goals of improving data mixes); Br. Expert Peterson ¶ 14 (similar).

Continue reading HERE.

About HackerNoon Legal PDF Series: We bring you the most important technical and insightful public domain court case filings.

This court case retrieved on June 25, 2025, from storage.courtlistener.com, is part of the public domain. The court-created documents are works of the federal government, and under copyright law, are automatically placed in the public domain and may be shared without legal restriction.