Table Of Links

- Memory Tagging Extension

- Speculative Execution Attack

4. Finding Tag Leakage Gadgets

- Tag Leakage Template

- Tag Leakage Fuzzing

- TIKTAG-v1: Exploiting Speculation Shrinkage

- TIKTAG-v2: Exploiting Store-to-Load Forwarding

6.1. Attacking Chrome

Finding Tag Leakage Gadgets

The security of MTE random tag assignment relies on the confidentiality of the tag information per memory address. If the attacker can learn the tag of a specific memory address, it can be used to bypass MTE—e.g., exploiting memory corruption only when the tag match is expected. In this section, we present our approach to discovering MTE tag leakage gadgets. We first introduce a template for an MTE tag leakage gadget (§4.1) and then present a template-based fuzzing to discover MTE tag leakage gadgets (§4.2).

4.1. Tag Leakage Template

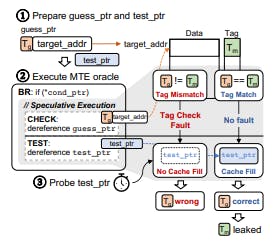

We first designed a template for a speculative MTE tag leakage gadget, which allows the attacker to leak the tag of a given memory address through speculative execution (Figure 1). The motivation behind the template is to trigger MTE tag checks in a speculative context and observe the cache state after the speculative execution. If there is any difference between tag match and mismatch, the attackers can potentially leak the tag check results and infer the tag

value. Since tag mismatch during speculative execution is not raised as an exception, such an attempt is not detected. We assume the attacker aims to leak the tag Tm assigned to target_addr. To achieve this, the attacker prepares two pointers: guess_ptr and test_ptr ( 1 ). guess_ptr points to target_addr while embedding a tag Tg— i.e., guess_ptr = (Tg«56)|(target_addr & ~(0xff«56)). test_ptr points to an attacker-accessible, uncached address with a valid tag.

Next, the attacker executes the template with guess_ptr and test_ptr ( 2 ). The template consists of three components in order: BR, CHECK, and TEST. BR encloses CHECK and TEST using a conditional branch, ensuring that CHECK and TEST are speculatively executed. In CHECK, the template executes a sequence of memory instructions to trigger MTE checks. In TEST, the template executes an instruction updating the cache status of test_ptr, observable by the attacker later.

Our hypothetical expectation from this template is as follows: The attacker first trains the branch predictor by executing the template with cond_ptr storing 1 and guess_ptr containing a valid address and tag. After training, the attacker executes the template with cond_ptr storing 0 and guess_ptr pointing to target_addr with a guessed tag, causing speculative execution of CHECK and TEST. If the MTE tag matches in CHECK, the CPU would continue to speculatively execute TEST, accessing test_ptr and filling its cache line.

If the tags do not match, the CPU may halt the speculative execution of TEST, leaving the cache line of test_ptr unfilled. Consequently, the cache line of test_ptr would not be filled. After executing the template, the attacker can measure the access latency of test_ptr after execution, and distinguish the cache hit and miss, leaking the tag check result ( 3 ). The attacker can then brute-force the template executions with all possible Tg values to eventually leak the correct tag of target_addr.

Results. We tested the template on real-world ARMv8.5 devices, Google Pixel 8 and Pixel 8 pro. We varied the number and type of memory instructions in CHECK and TEST, and observed the cache state of test_ptr after executing the template. As a result, we identified two speculative MTE leakage gadgets, TIKTAG-v1 (§5.1) and TIKTAG-v2 (§5.2) that leak the MTE tag of a given memory address in both Pixel 8 and Pixel 8 pro.

4.2. Tag Leakage Fuzzing

To automatically discover MTE tag leakage gadgets, we developed a fuzzer in a similar manner to the Spectre-v1 fuzzers [48]. The fuzzer generates test cases consisting of a sequence of assembly instructions for the speculatively executed blocks in the tag leakage template (i.e., CHECK and TEST). The fuzzer consists of the following steps: Based on the template, the fuzzer first allocates memory for cond_ptr, guess_ptr, and test_ptr. cond_ptr and guess_ptr point to a fixed 128-byte memory region individually. test_ptr points to a variable 128-byte aligned address from a 4KB memory region initialized with random values.

Then, the fuzzer randomly picks two registers to assign cond_ptr and guess_ptr from the available registers (i.e., x0-x28). The remaining registers hold a 128-byte aligned address within a 4KB memory region or a random value. The fuzzer populates CHECK and TEST blocks using a predefined set of instructions (i.e., ldr, str, eor, orr, nop, isb) to reduce the search space. Given an initial test case, the fuzzer randomly mutates the test case by inserting, deleting, or replacing instructions to generate new test cases.

The fuzzer runs test cases in two phases:

(i) a branch training phase, with cond_ptr storing true and guess_ptr containing a correct tag; and

(ii) a speculative execution phase, with with cond_ptr storing false and guess_ptr containing either a correct or wrong tag. The fuzzer executes each test case twice. The first execution runs the branch training phase and then the speculative execution phase with the correct tag. The second execution is the same as the first, but the only difference is to run the speculative execution phase with the wrong tag.

After each execution, the fuzzer measures the access latency of a cache line and compares the cache state between the two executions. This process is repeated for each cache line of the 4KB memory region. If a notable difference is observed, the fuzzer considers the test case as a potential MTE tag leakage gadget.

Results. We developed the fuzzer and tested it on the same ARMv8.5 devices. As a result, we additionally identified variants of TIKTAG-v1 (§5.1) that utilize linked list traversal. The fuzzer was able to discover the gadgets within 1-2 hours of execution without any prior knowledge of them.

This paper is