This is a Plain English Papers summary of a research paper called Baichuan-M3: Modeling Clinical Inquiry for Reliable Medical Decision-Making. If you like these kinds of analysis, join AIModels.fyi or follow us on Twitter.

The gap between answering questions and making decisions

Medical AI today operates like a vending machine: insert question, receive answer. But medicine doesn't work that way. A real physician doesn't wait passively for complete information. They probe. They notice what's missing and ask targeted questions to fill the gaps. They hold multiple threads of evidence in mind and weave them into a coherent picture. And critically, they know when to admit uncertainty rather than confidently inventing answers.

Baichuan-M3 represents a fundamental shift in how we approach medical AI. Instead of building systems that answer medical questions, the researchers built a system that inquires like a clinician. The insight is simple but powerful: the difference between a tool that responds and a tool that actually helps doctors make decisions lies in teaching the AI to think through a consultation the way an experienced physician does.

Why current medical AI fails at real consultations

Existing medical language models treat every interaction as a discrete question-answer pair. You describe a symptom, they produce a diagnosis. This works fine when you're asking a search engine, but it breaks down in actual clinical settings where the real work is figuring out what to ask next.

Consider what a real doctor does when you describe a headache. They don't launch immediately into diagnostic categories. They ask: "How long has this been happening? Sharp or throbbing? Does light bother you? Any stress recently?" These aren't random questions. They're systematic probes designed to disambiguate among competing possibilities. Each answer narrows the space of likely diagnoses.

Current medical AI systems skip this detective work entirely. They either predict a diagnosis from whatever information was given (often incomplete), or they retrieve pre-written answers from training data. Neither approach captures what actually makes clinical reasoning powerful: the ability to recognize what you don't know and strategically uncover it.

This becomes dangerous in open-ended consultations where information is naturally incomplete. The model either gives up (unhelpful) or makes confident claims beyond its knowledge (worse than unhelpful). There's no middle ground where it can say "I need more information before I can reason about this reliably."

What physicians actually do

A physician's cognitive process is learnable and systematic. It's not magic. It's a pattern that repeats across consultations.

The pattern looks like this: examine the patient, notice what's missing from the picture, ask targeted follow-ups, synthesize information across multiple data points, reason toward a conclusion, and maintain awareness of remaining uncertainty. This workflow is the target. Baichuan-M3 isn't trying to build a medical encyclopedia. It's trying to replicate a thinking process.

The paper identifies three core capabilities that make this process work:

Proactive information acquisition means recognizing that you don't have enough information and asking the right clarifying questions to resolve ambiguity. Not waiting passively for all data upfront, but dynamically constructing your understanding.

Long-horizon reasoning means holding multiple threads of evidence simultaneously across many turns of dialogue and weaving them into a coherent diagnostic narrative. A single symptom might mean nothing. But symptom plus lab result plus timeline plus patient history, synthesized together, often points clearly toward an explanation.

Adaptive hallucination suppression means knowing the boundary between what you actually know and what you're guessing. Honest uncertainty is clinically useful. Confident falsehoods are dangerous.

Most medical AI today fails at all three. The architecture Baichuan-M3 introduces addresses each directly.

The three-stage training pipeline

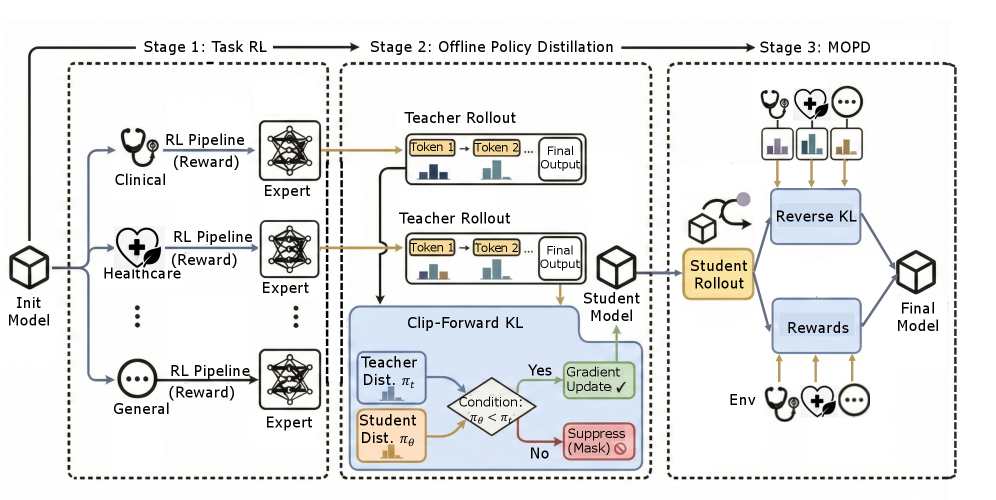

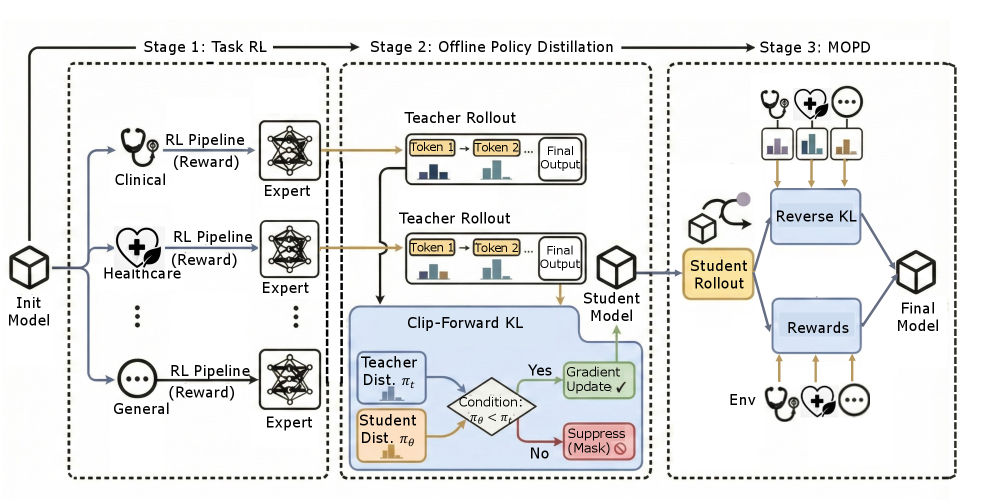

Rather than trying to learn these skills from standard supervised learning alone, the researchers built a three-stage training pipeline where each stage builds toward the desired behavior.

An illustration showing the three-stage pipeline: supervised fine-tuning, segmented reinforcement learning, and fact-aware reinforcement learning stacked vertically

Stage one: supervised fine-tuning starts with real physician consultations. The model learns by imitation. It watches how experienced doctors structure their inquiries, synthesize information, and conclude. This builds baseline clinical behavior without requiring the complex machinery of reinforcement learning. It's like a medical resident watching experienced physicians work.

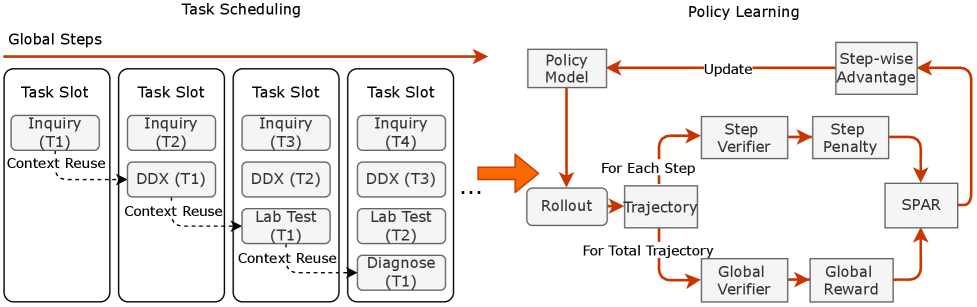

Stage two: segmented reinforcement learning moves beyond imitation into optimization. The model now generates full consultation dialogues and receives feedback on quality. Did it ask questions that meaningfully narrowed down the diagnosis? Did it synthesize information coherently? Did it make confident claims without justification? The model learns which behaviors lead to better clinical outcomes.

Segmented pipeline RL diagram on the left showing how consultations are generated and evaluated, and policy learning algorithm on the right showing the mathematical optimization loop

This is where reinforcement learning becomes essential. You can't teach clinical judgment with supervised learning alone because "what a good consultation looks like" isn't a single correct answer you can show the model. It's a quality of reasoning unfolding over many turns. You have to define what good means mathematically (quality of inquiry, reasoning coherence, appropriate confidence) and then optimize toward it.

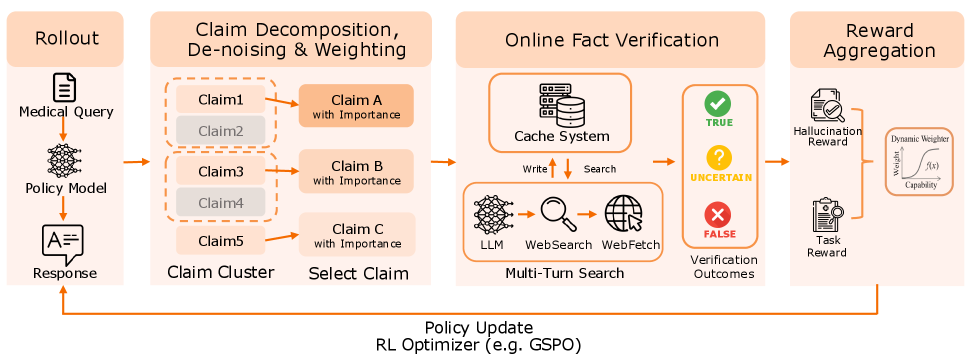

Stage three: fact-aware reinforcement learning tackles hallucination at the source. The model learns to check itself before speaking. During training, the system inspects what the model actually knows versus what it's tempted to claim. When the model tries to say something it can't justify from its training knowledge, it gets penalized.

Fact-aware reinforcement learning algorithm showing the verification step and knowledge alignment loss

This is the novel part. Most approaches treat hallucination as a filtering problem: let the model say whatever it wants, then post-process to catch lies. This approach bakes honesty into the optimization process itself. The model becomes strategically honest not because it's instructed to, but because the learning signal rewards consistency between its internal knowledge and its claims.

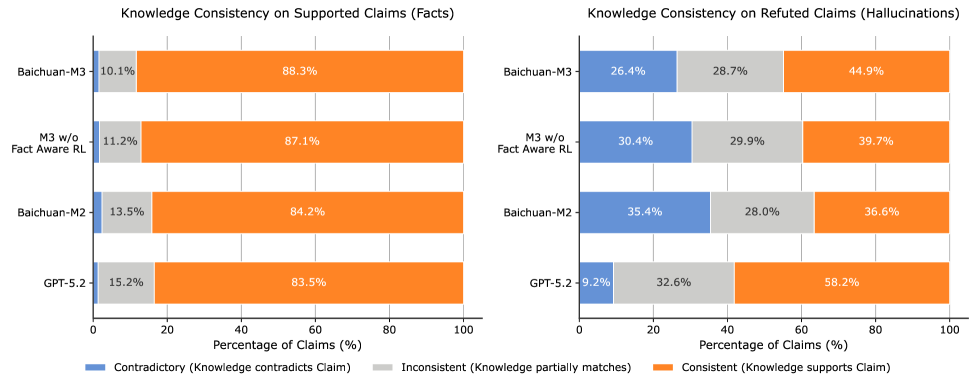

The boundary between what a model knows and what it guesses gets explicit during this phase. The researchers categorize outputs into three states: consistent (internal knowledge aligns with the claim), inconsistent (partial mismatch), and contradictory (the model claims something it actually knows to be false). This taxonomy itself reveals how much more precise we can be about hallucination when we look inside the training process.

Knowledge boundary alignment analysis showing three categories: consistent outputs in green, inconsistent in yellow, and contradictory in red with examples

Testing whether it works

The architecture is elegant in theory, but does it produce measurably better clinical decision support? The researchers tested each capability independently, then holistically on realistic consultation tasks.

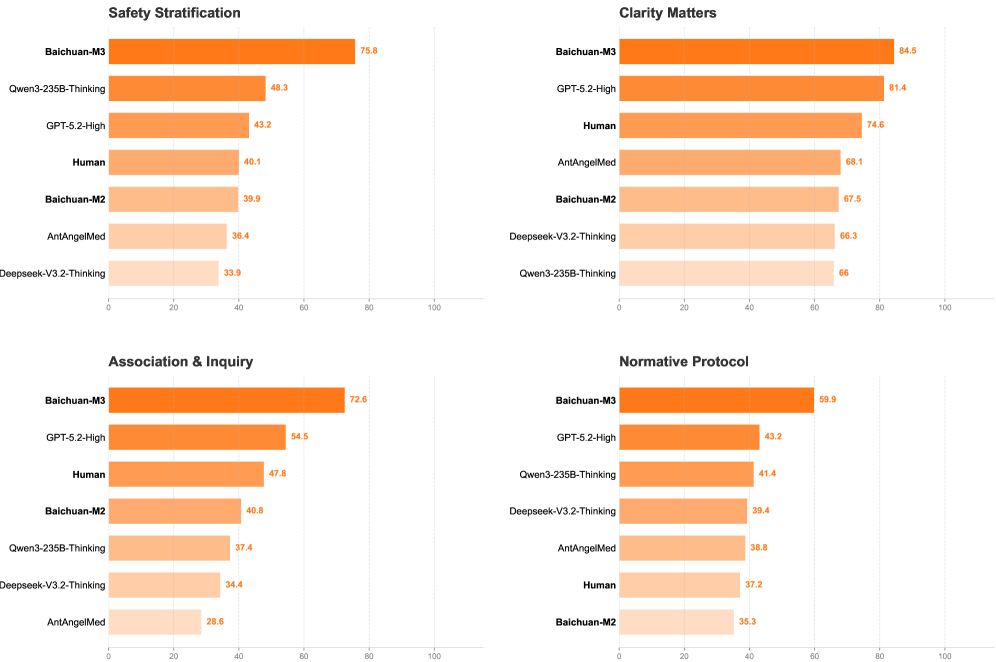

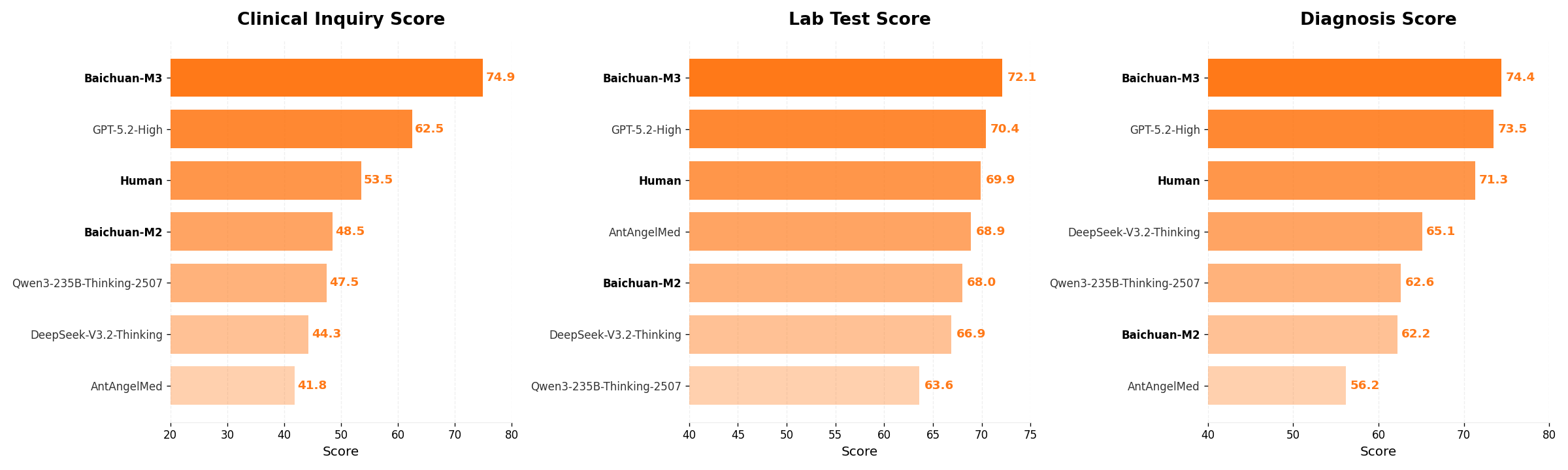

Inquiry quality: The first capability is proactive information acquisition. Can the model ask better diagnostic questions than existing systems? The paper introduces HealthBench-Hallu to measure this specifically. Rather than just checking if the final diagnosis is correct, the evaluation measures how the model gets there.

Detailed breakdown of inquiry capabilities showing which types of questions the model asked and how effectively it narrowed down possibilities

Baichuan-M3 doesn't just ask more questions. It asks better questions. Early in conversation, it identifies key distinguishing factors and probes those systematically. This is higher-order reasoning: not just "ask a question" but "ask the question that most efficiently reduces diagnostic uncertainty."

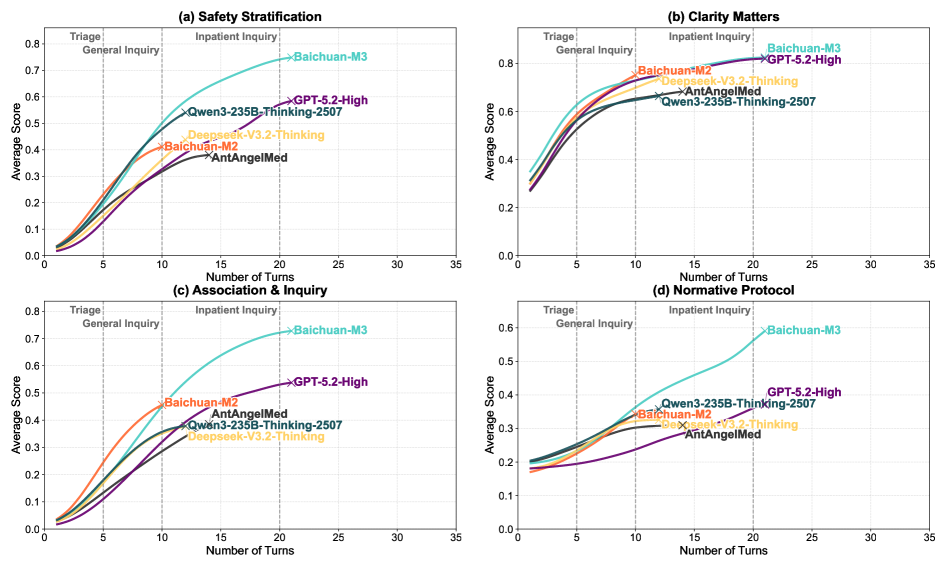

Long-horizon reasoning: Over five or ten turns of conversation, a physician accumulates scattered evidence. A good physician doesn't treat these as separate facts. The evidence synthesizes into a pattern. The model's performance across dialogue turns shows whether this synthesis is actually happening.

Graph showing model performance and reasoning quality improving across dialogue turns as more information arrives

The model doesn't plateau as the conversation deepens. With each turn, its reasoning incorporates new information more cohesively. It's not just accumulating facts in an unordered list. It's revising its working hypothesis in response to new evidence and building a unified explanation. This is the hallmark of actual reasoning, not surface pattern-matching.

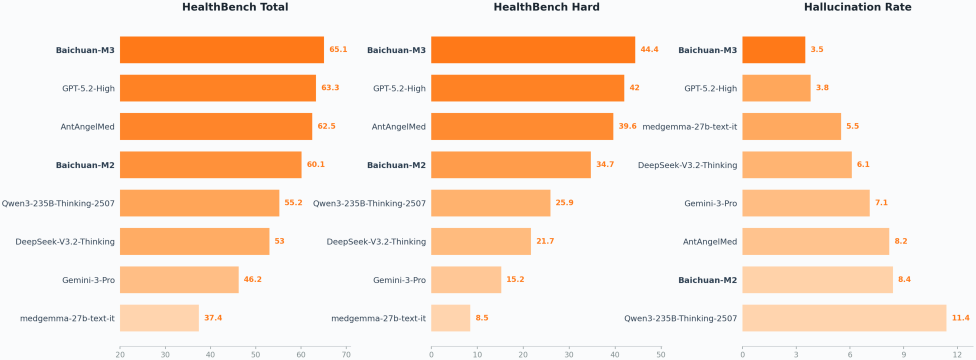

Hallucination suppression: This is where the paper makes its boldest claim. The HealthBench and ScanBench benchmarks measure two things: factual accuracy (does the model make correct claims?) and appropriate uncertainty (when the model doesn't know something, does it admit it rather than confabulate?). The second metric is harder to measure but more important clinically.

Head-to-head comparison on ScanBench showing Baichuan-M3 versus GPT-5.2 across multiple dimensions, with particular improvements visible in factual reliability and uncertainty appropriateness

A model that says "I'm not sure" on 50% of questions might be more useful than one answering 90% with 10% of those answers being confidently false. The data show Baichuan-M3 doesn't just avoid hallucinations through luck. Its internal consistency is measurably higher. When you trace back what it claims to what its parameters actually encode, there's better alignment. This suggests the fact-aware RL training genuinely shaped behavior.

Comprehensive performance: HealthBench is a comprehensive evaluation spanning multiple conditions, presentation styles, and complexity levels. The fine-grained comparison shows where improvements are happening, not just that they exist.

Overall performance comparison on HealthBench showing Baichuan-M3 outperforming GPT-5.2 across multiple metrics

Fine-grained breakdown comparing M2 versus M3 across different themes and axes, showing improvements concentrated in inquiry capability and reasoning coherence

The improvement isn't uniform. On cases where inquiry is more valuable, where the patient presentation is complex or ambiguous, the gap widens significantly. This suggests the model genuinely learned the intended behavior rather than just improving general language quality.

What this reveals about AI training

Baichuan-M3 is a medical system, but the contribution extends beyond healthcare. The three-stage pipeline is really a blueprint for how to teach any AI system to think systematically.

Most safety research treats hallucination as a problem to patch after training: filter outputs, add guardrails, detect and label uncertain statements. Baichuan-M3 suggests something different. Hallucination isn't an implementation bug. It's a failure of the training objective. If your training process rewards the model for being right without penalizing it for being confident while wrong, hallucination becomes rational behavior. Fix the training objective, and honesty emerges as an optimized solution rather than as a bolted-on constraint.

The same logic applies to inquiry. You don't teach a model to ask good questions by adding a post-hoc question-generation module. You teach it by making question-quality part of the training objective and optimizing for it directly. Capabilities cascade from alignment between what you measure and what you want.

This also hints at a broader principle: training objectives should reflect task structure. In medicine, the task is iterative and uncertain. The training process needs to acknowledge that. You can't optimize for single-answer accuracy when the real task is multi-turn reasoning. The mismatch between training signal and actual task requirement is often where AI systems fail quietly, producing confident-sounding nonsense in realistic conditions.

The related work on medical AI reasoning provides context for how this fits into the broader landscape. Previous iterations like Baichuan-M2 focused on scaling medical knowledge and verification, while Baichuan-M1 pushed raw medical capability. Baichuan-M3 represents an architectural shift toward systematic process rather than just knowledge or verification layers. The progression shows how medical AI is moving toward building physician-like workflows rather than factual databases.

Where this approach leads

The immediate application is clear: better clinical decision support that actually investigates rather than just responds. But the implications reach further.

Any domain where reasoning is iterative and uncertainty is inherent could benefit from this framework. Customer support systems that diagnose problems, scientific research tools that guide investigation, technical debugging assistance, legal analysis platforms, all would benefit from learning to ask what they don't know rather than confidently guessing.

The deeper contribution is methodological. This work shows that you can align AI behavior with complex real-world processes by carefully structuring the training objective. You don't need magic. You need clear understanding of what the process actually looks like, then training that rewards moving toward it. This is why the paper spends so much time making explicit what a physician's workflow actually is. You can't optimize what you haven't defined.

For medical AI specifically, this represents maturation from "factual question-answering" to "decision support." The systems get useful not by knowing more facts, but by knowing how to use incomplete information responsibly. That's a harder problem. Baichuan-M3 shows it's solvable through thoughtful training architecture and clear evaluation of what actually matters clinically.