This is a Plain English Papers summary of a research paper called STEP3-VL-10B Technical Report. If you like these kinds of analysis, join AIModels.fyi or follow us on Twitter.

The efficiency paradox that rewrites multimodal AI

Vision-language models face a cruel choice. Stay small and efficient, and you sacrifice reasoning capability. Scale to hundreds of billions of parameters, and you handle complex visual tasks effortlessly but burn enormous computational resources. The field has accepted this tradeoff as inevitable, like two ends of a rope you can only hold one end of at a time.

STEP3-VL-10B breaks this assumption by asking a different question: what if the bottleneck isn't model size at all, but how the model allocates its thinking?

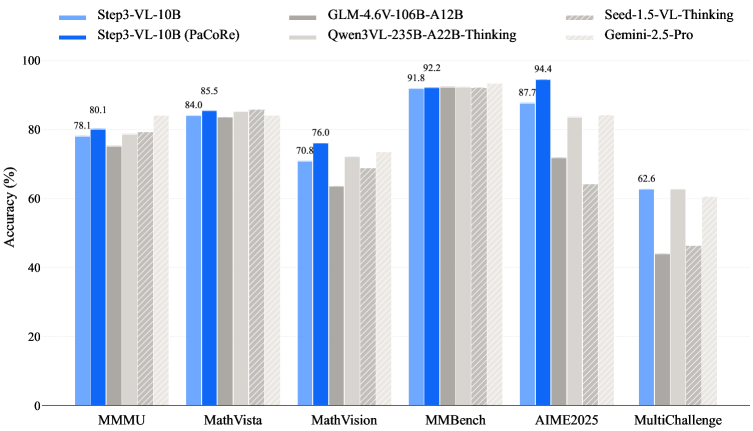

A 10 billion parameter model that rivals systems 10 to 20 times larger sounds like marketing. The paper proves it's architecture. The approach combines three strategic choices made in sequence: unfrozen joint pre-training of vision and language components on 1.2 trillion multimodal tokens, over 1000 iterations of reinforcement learning that teaches the model to reason more efficiently, and a test-time reasoning method called Parallel Coordinated Reasoning that generates multiple interpretations of an image before synthesizing a final answer. The results are striking. STEP3-VL-10B reaches 92.2% on MMBench, 80.11% on MMMU, 94.43% on AIME2025, and 75.95% on MathVision, matching or exceeding models like GLM-4.6V-106B, Qwen3-VL-235B, and proprietary systems like Gemini 2.5 Pro.

But the real insight runs deeper than benchmark numbers. This work demonstrates that reasoning ability comes from multiple sources, and parameter count is only one of them. That realization changes what's possible for efficient AI.

Teaching vision and language to grow up together

Traditional vision-language models treat perception and language as separate problems that happen to live in the same system. A frozen Perception Encoder extracts visual features. A language model interprets those features. They've never learned to understand each other.

STEP3-VL-10B starts differently. During pre-training, both the Perception Encoder and the Qwen3-8B language decoder receive gradients simultaneously. They co-evolve across 1.2 trillion multimodal tokens. The Perception Encoder learns what patterns the language model actually cares about understanding. The language model learns what kinds of visual information matter for reasoning.

This sounds like a small change. It's not. Consider how humans learn language and visual understanding. You don't learn to recognize objects in isolation, then separately learn to talk about them. You learn them together, each informing the other. When you learn the word "bridge," you simultaneously understand what bridges look like, why they matter structurally, and how to reason about them. That integration is what STEP3-VL-10B captures at scale.

The scale matters too. 1.2 trillion tokens is large enough that both components can specialize meaningfully while still learning deep interdependencies. Too small, and emergent reasoning patterns never develop. Too large without the right architecture, and you're wasting compute. This number reflects the point where the two components have learned to cooperate fully.

The foundation established during pre-training is silent and invisible in benchmarks. You won't see a paper that says "unfrozen pre-training alone gave us 2% on MMBench." But without this step, the rest of the approach doesn't work. The model needs to enter RL training already understanding vision and language as integrated domains, not after-the-fact combinations.

Learning to reason through structured iteration

Pre-training establishes foundations. Reinforcement learning teaches strategy. The paper implements what it calls RLVR (Reinforcement Learning with Vision-Reasoning), running over 1000 iterations where the model generates multiple candidate reasoning chains for visual problems, receives rewards based on reasoning quality and correctness, and updates its weights to prefer better patterns.

What happens during this process is revealing. Figure 2 shows two curves that initially seem contradictory. The reward curve climbs steadily without saturating, indicating the model keeps finding room for improvement. Simultaneously, the average number of tokens generated initially spikes then decreases back toward baseline levels. This isn't a sign of failure or saturation. It's the opposite. The model is learning to reason more efficiently, achieving the same quality of reasoning in fewer tokens.

Performance trends showing reward increasing while token count decreases

RLVR dynamics: reward continuously improves (left) while the model learns to reason more concisely, reducing rollout tokens after initial exploration (right).

This pattern indicates genuine learning, not mere memorization or output inflation. The model isn't cheating by making longer outputs to seem smarter. It's developing better internal representations of visual reasoning. Early RL iterations teach basic structured thinking. Later iterations refine edge cases and teach multi-step integration across multiple hypotheses.

Figure 3 tracks this progress on representative benchmarks. Metrics on reasoning tasks (the kind where visual hypothesis exploration matters most) and perception tasks (the kind where all models converge to similar performance) both show the same pattern: rapid initial growth followed by steady improvement that mirrors the reward dynamics.

Benchmark performance over RL iterations

Performance gains during RLVR track reward improvements: rapid initial growth followed by steady gains, indicating sustained learning rather than saturation.

The convergence between reward trends and benchmark trends confirms something important. The RL procedure isn't optimizing for gaming metrics or statistical artifacts. It's genuinely teaching the model better reasoning behavior, and that behavior transfers directly to standard benchmarks. This is crucial for believing that the approach will generalize beyond the specific tasks used during training.

Why test-time scaling beats parameter scaling

Here's where the conceptual breakthrough becomes concrete. Instead of scaling the model by making it larger, STEP3-VL-10B scales it at inference time through Parallel Coordinated Reasoning.

The mechanism is elegant. For a complex visual reasoning task, the model doesn't generate one answer. It generates multiple competing interpretations of the visual input. For a diagram, it might ask: what if the key relationship is spatial? What if it's conceptual? What if these elements are functionally connected rather than physically arranged? Each interpretation proceeds through independent reasoning chains. Then the model synthesizes across these chains, considering how different interpretations support or contradict each other, arriving at a final answer that integrates multiple hypotheses.

The term "Parallel Coordinated" captures both elements. The reasoning chains run in parallel, making efficient use of compute. But they coordinate, with the model tracking how different interpretations relate to each other. The final answer emerges from synthesis, not from selecting the loudest individual chain.

Figure 1 illustrates the consequence. STEP3-VL-10B bridges a gap that previous models couldn't cross. On pure perception tasks, where extracting visual information is straightforward, all models converge to similar performance. The curve flattens. But on complex reasoning tasks, where multiple interpretations are possible and need reconciliation, larger models normally pull away dramatically. STEP3-VL-10B with PaCoRe doesn't follow that pattern. Its performance on reasoning tasks rises alongside the perception baseline, breaking the historical correlation between reasoning difficulty and model size.

Comparison showing Step3-VL-10B bridging perception and reasoning gaps

STEP3-VL-10B with PaCoRe achieves frontier performance on both perception and reasoning tasks, bridging the traditional efficiency-capability gap.

This test-time scaling trades compute at inference for parameters in training. For many real-world applications, this is a profound advantage. You're spending inference tokens (generated at runtime) instead of training-time parameters. A batch processing system can spend more compute on a single request to get better accuracy. An interactive system can dial down test-time reasoning if latency becomes critical. An on-device application gets a model 10x smaller than the alternative while maintaining comparable reasoning capability. The flexibility is as valuable as the benchmark numbers.

This approach connects to broader work on test-time scaling across the field. OpenAI's o1 model and Anthropic's extended thinking both explore similar territory for language reasoning. STEP3-VL-10B demonstrates that the principle isn't language-specific. Multimodal systems can benefit equally from allocating more compute to test-time reasoning, particularly when visual interpretation ambiguity is involved.

Where the model actually excels

The benchmark results reveal something important: the approach's strengths are concentrated where reasoning matters most.

On MMBench (92.2%) and MMMU (80.11%), STEP3-VL-10B performs competitively but not dramatically ahead of the largest models. These benchmarks test perception and basic understanding. Multiple visual interpretations don't help much when the task is straightforward pattern recognition. The model shines on tasks where it needs to explore hypotheses.

Look at AIME2025 (94.43%), a competition mathematics benchmark that requires integrating visual information, problem setup, and multi-step reasoning. The model doesn't just extract numbers from diagrams; it interprets spatial relationships, reasons through constraints, and verifies answers against the original problem. MathVision (75.95%), focused specifically on visual mathematics and geometry, shows similar strength. These tasks demand the kind of hypothesis exploration that PaCoRe provides.

The split between perception and reasoning isn't accidental. It reveals the architecture's actual operating principle. When visual tasks are straightforward, you don't need multiple interpretations. When they require reasoning through ambiguity or multi-step inference, exploring alternative interpretations becomes powerful. The model learned to allocate its test-time reasoning where it's most valuable.

This specificity matters for practitioners considering deployment. STEP3-VL-10B is exceptional for applications with complex visual reasoning: mathematics and geometry, engineering diagram analysis, scientific image interpretation, medical imaging in domains requiring reasoning about relationships rather than classification. For tasks where perception dominates and reasoning is minimal, a smaller model might suffice.

What the approach can't do (yet)

Every elegant solution has boundaries. Understanding them prevents misuse and clarifies where different approaches remain necessary.

Latency becomes a constraint when test-time reasoning is needed. Parallel Coordinated Reasoning works by generating multiple reasoning paths. A system requiring sub-100-millisecond response times can't afford this exploration. Real-time interactive applications, mobile interfaces with strict latency budgets, and streaming systems where decisions must be made instantly need different architectures or models optimized for speed over reasoning quality.

The language backbone, borrowed from Qwen3-8B, becomes a limitation for tasks with minimal visual content or requiring extensive reasoning over pure language. A problem involving a single small diagram and 50 pages of text might not benefit from STEP3-VL-10B's strengths. Large language models with stronger language modeling components would perform better. The model was optimized for vision-language integration, not language-heavy tasks.

Domain specialization matters too. The training emphasized visual reasoning across diverse domains. Specialized fields requiring deeply specific language knowledge (legal document understanding with minimal images, scientific text with citation-heavy reasoning, domain-specific jargon) might see better results from models trained specifically for those domains. STEP3-VL-10B's strength is breadth; specialized applications might trade some breadth for depth elsewhere.

These limitations aren't failures. They're the natural boundaries of an approach optimized for specific tradeoffs. A smaller, faster model for latency-critical applications. A larger language backbone for language-heavy reasoning. These coexist with STEP3-VL-10B in a broader toolkit rather than being replaced by it.

The research reproducibility layer

The paper releases the full model suite open-source. This is more than a nice addition to the research narrative; it's a statement about how knowledge should move in fast-moving fields.

Open release means researchers can use STEP3-VL-10B directly, fine-tune it for specific domains, and study what actually drives its performance rather than inferring from published claims. Training details sufficient for reproduction are included, though not every step-by-step training configuration. The benchmark evaluation procedures are documented clearly enough that future work can claim improvements with confidence rather than uncertainty about whether they used the same setup.

This matters because multimodal AI is moving fast. When models are proprietary and benchmarked behind those companies' methodologies, research gets gated. One group's research direction becomes the constraint for a thousand other researchers trying to build on it. Open models and reproducible baselines accelerate progress across the field. They also build trust in claims. When someone says "our new method beats STEP3-VL-10B," the community can verify whether that's true, whether they're testing the same way, and whether the comparison is fair.

The release also matters for practitioners. A frontier-performing open model at 10 billion parameters is genuinely valuable for on-device inference, cost-effective deployment, and experimentation in resource-constrained settings. Organizations can use this as a baseline, fine-tune it for their domains, and maintain control over their systems rather than relying on proprietary APIs.

Reframing how multimodal AI scales

STEP3-VL-10B is a specific model. It's also a proof of concept that challenges how the field thinks about scaling multimodal systems.

The traditional frame went like this: larger model equals smarter model, so efficiency means making models smaller while accepting capability reductions. The new frame this work enables is more nuanced. Reasoning capability comes from four sources: parameter count, pre-training scale, post-training refinement through RL, and test-time compute allocation. The optimal mix depends on the application. A research system where latency doesn't matter might push hard on test-time compute. A mobile application might minimize both parameter count and test-time reasoning. An on-device system might increase parameter count slightly to reduce test-time overhead.

This shift isn't theoretical. Major AI labs are already exploring test-time scaling for language reasoning. OpenAI's o1 model represents a massive commitment to test-time compute. Anthropic's extended thinking explores similar scaling. STEP3-VL-10B shows this principle works equally well for multimodal systems, where visual ambiguity and interpretation complexity create natural opportunities for hypothesis exploration.

The practical implications cascade outward. Future multimodal systems might look less like "bigger models" and more like "smarter inference procedures." A 10 billion parameter model becomes competitive with 100 billion parameter models through better reasoning allocation, not through different training data or longer training. This opens possibilities for cost-effective scaling, edge deployment that maintains frontier reasoning capability, and flexible systems where you can trade inference cost for quality per request.

The field is learning that the frontier of multimodal AI doesn't need to be a frontier of model size. It can be a frontier of architectural innovation, test-time reasoning, and thoughtful resource allocation. STEP3-VL-10B demonstrates that this isn't a small efficiency gain at the margins. It's a fundamental rethinking of how to build capable systems that competes directly with massive parameter-scaling approaches.