It has now been a few months since I passed the AWS Solutions Architect Exam. When I entered into the exam, I had a lot of confidence. I had completed all of the Coursera labs, deployed the sample applications to the practice console, and identified which AWS Services were best suited for specific use cases. However, I have always wondered how everything I created was confined within the Coursera Sandbox environment. There are guardrails all around, so I could make mistakes and the world wouldn't come to an end. I would never receive a large monthly invoice with my name on it due to a failure.

At the same time, I had begun to self-teach Nuxt.js by creating a contact manager application. This article focuses less on implementation mechanics and more on architectural judgment, cost considerations, and operational realities that are often ignored in standard tutorials. While nothing fancy, the contact manager application stored names, telephone numbers, and e-mail addresses. I wanted to create a contact manager application that simply allowed me to test a framework, and therefore I did not need to worry about pleasing anyone else. However, I wanted to put my Nuxt.js application onto AWS. Therefore, I decided to go big. Actually, I decided to go huge.

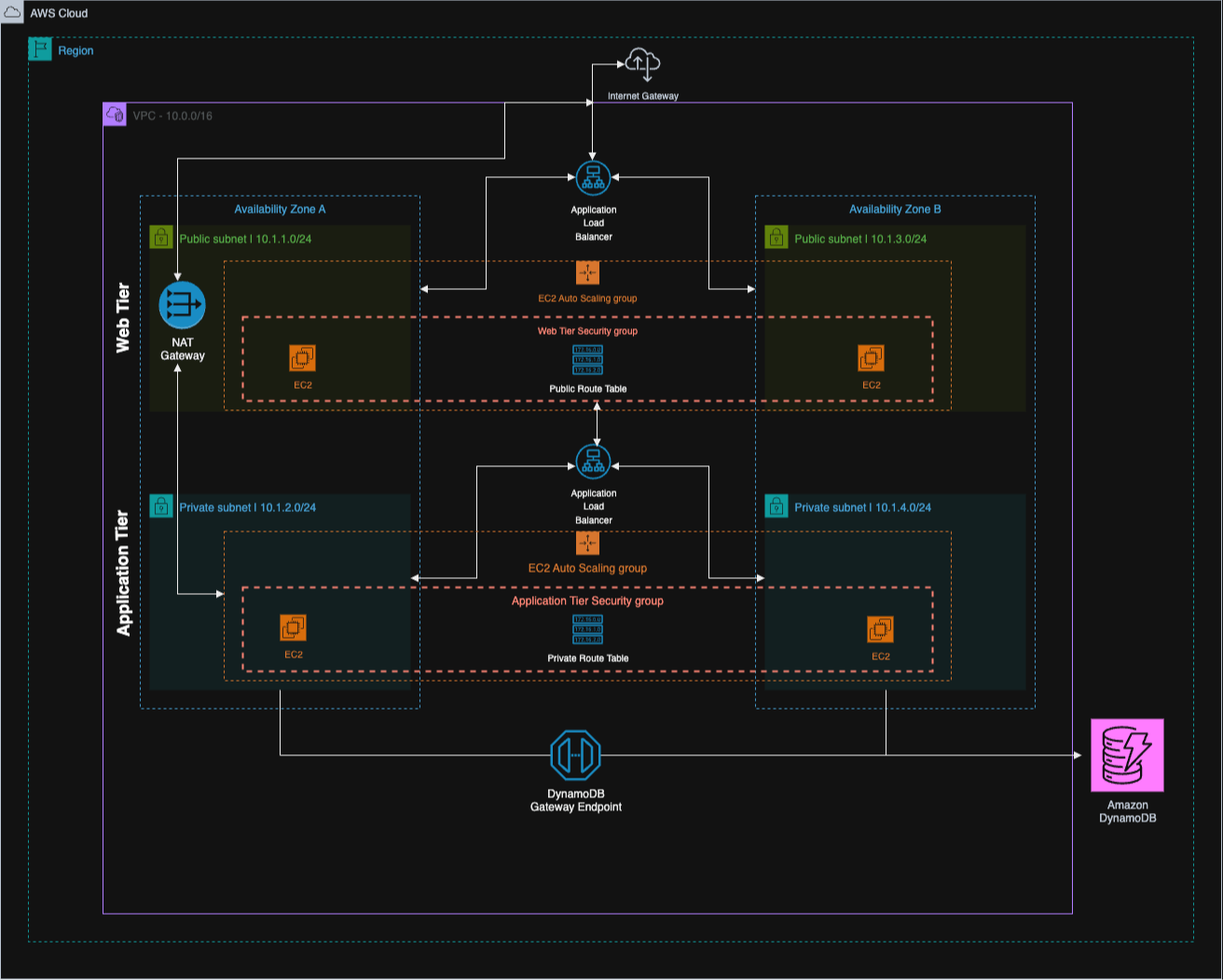

Two public subnets, two private subnets, load balancers in front of both tiers, and security groups referencing each other. I spent many hours in draw.io making the architecture diagram appear as if I had hired a consulting firm and paid thousands of dollars for it to be created. Ridiculous for an application that stores telephone numbers? Yes, absolutely. That was the point.

Tutorials will tell you what to build. Tutorials will not teach you what happens when your monthly invoice arrives with a line item that you do not recognize. Tutorials will omit the 45 minutes you will spend determining why traffic will not flow between subnets. Also, the practice environment provided by Coursera will not provide you with that anxious moment when you realize that a NAT Gateway has been running for 14 days.

Who Am I Writing This For?

Myself 6 months ago. That is whom I kept thinking about while I wrote this.

Solo developers attempting to find their way on AWS alone. Small startup teams where "the team" is you and someone else in a Slack channel. Anyone that has read a dozen Medium posts explaining the pros and cons of EC2 vs Lambda and still left confused.

This likely is not for you if you are working for a company with platform engineers and on call rotations. You have people whose primary function is figuring this stuff out.

My experience was much different. I am pretty sure this application receives almost no traffic. Most days, I am the only user. I do not have an on-call rotation because I do not have anyone to rotate with. I cannot predict when users will arrive. This uncertainty has influenced my decisions more than I initially thought.

The Application

Contact Keeper. Log in, add people, and search for them later. Basic CRUD. I have probably built some variation of this a dozen times while learning new frameworks/stacks.

Vue 3 with Nuxt.js on the frontend. I had been wanting to try Nuxt.js, and this seemed like the perfect opportunity to experiment with it. Node & Express on the backend. A stack I have used extensively in production systems.

Database selection was somewhat interesting. I ended up choosing DynamoDB primarily because I did not want to pay $15 per month for an RDS instance sitting idle while I tested. I wrote schemas using Dynamoose, which ultimately proved to be a good decision. Years of struggling with Mongoose on MongoDB projects made the patterns feel very familiar. One less thing to figure out.

Additionally, I chose to implement cursor-based pagination from the beginning. I learned this the hard way on a Laravel project. We implemented offset-based pagination (like just about everyone), and it performed perfectly well until we hit approximately 50k records. Then suddenly every page load took forever. Users complained. Database performance suffered. We removed it and replaced it with cursor-based pagination. I was determined to avoid making the same mistake again.

The application performed fine locally. Getting it onto AWS is where things got expensive.

How I Put Everything Together

Building the architecture diagram took significantly longer than expected. In three rounds of draw.io, deleting stuff, second-guessing myself, and moving boxes around. I finally figured things out. It felt tedious at the time; however, it ultimately helped me connect some dots that I could have otherwise messed up on.

First hit the internet-facing stuff. That's my web tier, living in two public subnets (10.1.1.0/24 in one availability zone, 10.1.3.0/24 in the other). Traffic hits an Internet Gateway, then gets distributed via an Application Load Balancer, and then lands on EC2 instances running the Nuxt app. There's an Auto Scaling Group wrapped around them. I used two AZs because most tutorials recommend it as standard practice.

Behind that wall is the application tier. Private subnets this time: 10.1.2.0/24 and 10.1.4.0/24. Another load balancer here, but internal. This one only communicates with the web tier; nothing from the outside world can reach it. The Express API runs on its own EC2 instances back here. When those boxes need to call their home, pull npm packages, or hit external APIs, they hit the NAT Gateway.

DynamoDB is at the back, accessible via a VPC Gateway Endpoint. This prevents traffic from going to the public internet.

This is where I wasted the most time. I had originally implemented Network ACLs on top of my security groups as another layer of security. The textbook approach; correct? However, my traffic continued to die silently. No errors. Nothing coming through.

Spent considerable time verifying and reverifying rules. Ultimately tore out the NACLs. Security Groups handle this just fine. They're stateful, so they keep track of connections appropriately, and when something fails, you can actually figure out why. NACLs are stateless, and debugging is horrible. Maybe they make sense with a dedicated network team. I don't have that.

Was DynamoDB a Good Choice?

Every access pattern in this app is a single operation. Get user by email. Get user by ID. Get contacts for a user. Get one contact by ID. Search within a user's contacts.

All single partition stuff. No joins. No aggregation across users. DynamoDB does this easily.

The pricing worked in my favor. On demand means I only pay for what I'm using. When nobody is using the app, I'm basically paying nearly nothing. An RDS instance would've cost me $12 to $15 a month just to exist.

VPC Gateway Endpoint

Free. Keeps DynamoDB traffic local to AWS rather than routing through the NAT Gateway. As the NAT Gateway charges per GB processed. Every contact list load, every search, and every save remains local. Create it and forget about it.

Two Availability Zones

No extra charge. If one data center has issues, the other will continue to run. The ALB will automatically handle failover.

Single AZ would've sufficed for my Contact App, but I wanted to understand multi AZ.

Two Load Balancers Seemed Like Overkill

Internet-facing ALB for the web tier. Internal ALB for the app tier. The backend is never directly exposed to the public internet.

Sounds good on paper. Then I looked at cost.

Each ALB costs about $16/month baseline. Two of them just sitting there? That's $32/month before a single user shows up. For my Contact App that may be able to handle a few dozen requests per day; spending thirty two dollars a month seems like a waste.

There's a better way. Single ALB; path-based routing. Any requests hitting /api/* go to backend instances; anything else goes to the frontend. Yes, your API becomes routable to the public internet. However, you'll still be authenticating each and every request, you'll still have CORS configured, and you'll still have your security groups locked down.

I went with two ALBs because I wanted to see how the setup worked in practice. If I was going to be spending money long-term? One ALB; no question.

Costs Were Worse Than Expected

Here are costs for each component:

t3.micro (two) in web tier: ~$15/month

t3.micro (two) in app tier: ~$15/month

ALB for external use: ~$16/month

ALB for internal use: ~$16/month

NAT Gateway: ~$32/month (baseline), plus data transfer.

DynamoDB: probably less than a couple of dollars a month due to minimal traffic.

~$95 to $100/month. Over $1,000/year.

That's for a contact app that probably gets looked at by three users at best.

Reservations will lower costs. Reserve for 12 months; save 30% to 40%. Then you'll pay ~$70 to $80 a month. Still high cost for something only three people will look at.

Another problem is: Auto Scaling Groups have a floor. Auto Scaling Groups will never go down to zero instances. Therefore, at 4am, when it is likely no one in the world is concerned with contacting management, those four instances are running idle, and I am being charged for them.

What Surprised Me Along The Way

NAT Gateway is expensive and misleading. I know it bills based on hours and gigabytes transferred. What I did not take into consideration is how much traffic is generated to reach it. npm install during deployment? NAT Gateway. Making calls to third-party APIs? NAT Gateway. Anything reaching the public Internet from private subnets? NAT Gateway. The $32/month base price is simply for having it. Actual data transfer is layered above that.

Even security groups are frustrating to debug. While they are far better than NACLs, the symptoms of incorrect rules are still timeouts. There is rarely a helpful error message. Silence. I spent an inordinate amount of time figuring out why the app tier would not accept connections from the web tier. Eventually, I discovered I had put the web tier's CIDR block instead of the security group ID for the web tier in the security group. CIDR blocks do not work well with scaling instances and getting new IPs. Security group references do not have this problem.

Auto Scaling essentially means Auto Healing at Low Traffic. I had Auto Scaling configured to ensure a minimum count of 1 per tier per Availability Zone (AZ), which resulted in a total of four instances. How many times did the Auto Scaling Group ever scale up? Zero. Too little traffic. The Auto Scaling Group was essentially replacing instances whenever the health checks failed. Helpful, but not what the name implies.

When Three-Tier EC2 Is The Right Choice

I realize that I spent most of this article complaining. That is not because the design is bad. I simply selected the wrong tool for what I built.

There are plenty of situations in which a three-tier setup like the one I described makes complete sense:

Traffic is very heavy and constant, flipping the entire economics model. At some point, once you are receiving tens of thousands of requests per second 24/7, reserved EC2 instances are usually cheaper than Lambda's charge per request.

There are workloads that simply need to last longer than 15 minutes. Lambda has a hard cap of 15 minutes, whereas if you are transcoding video, training machine learning models, or performing batch jobs that continue for hours, you need to use compute that does not disappear mid-task.

WebSockets are another example. Multiplayer games, live chat applications, and collaborative document editors require processes that maintain persistent connections to clients. Lambda's request-response model does not function well in these cases.

In regulated industries, auditors may require physical servers that can be pointed at. Healthcare, finance, or government organizations may not have a choice.

If your organization already has a mature platform team, then the friction I discussed will be part of normal operations. Entirely different calculation.

Your contact app does not fit into any of those categories. Your application may be different.

Looking Back

Now that VPCs make sense to me in a way that they did not previously, I can understand why they are necessary. It is not exam question sense. More like "I finally understand why my packets are vanishing" sense. Route tables, security groups, how NAT Gateway pricing slowly builds up on you. The costs accumulating week after week made the cost model tangible.

The larger lesson is learning when to disregard common wisdom. Three-tier architectures using EC2 are valid, battle-tested, and have been used to build mission-critical systems. Banks rely on it. Enterprises rely on it. For what I built, it was massive overkill.

The key takeaway wasn't how to build a three-tier architecture, but how quickly architectural "best practices" become liabilities when traffic, cost, and team size don't justify them.

Was I able to determine this without the expense of the experiment? Probably not. Some things you have to experience before they become real.

Next project: tear down and build a serverless application. API Gateway in front, Lambda processing the requests, and the same DynamoDB backend. Time to see if it is cheaper.

There is no such thing as a perfect architecture. You find the one that fits within your constraints and accept the compromises. Architectural maturity is less about knowing patterns and more about knowing when those patterns stop serving your constraints.