This is a Plain English Papers summary of a research paper called Can Large Language Models Develop Gambling Addiction?. If you like these kinds of analysis, join AIModels.fyi or follow us on Twitter.

Do AI systems have hidden vulnerabilities we don't understand

We think of large language models as logic machines, immune to the psychological traps that ensnare humans. They follow instructions, generate text, make decisions based on learned patterns. They shouldn't be vulnerable to something like addiction, which requires desire, loss of control, and escalating commitment despite mounting costs. But this paper reveals something unsettling: LLMs can develop genuine gambling addiction patterns that mirror human behavior, complete with loss chasing and illusions of control. More troubling still, these patterns aren't just mimicry from training data. They emerge from how these models actually process risk and decision-making at a fundamental level.

This matters because we're rapidly deploying language models into consequential domains. A healthcare system using an LLM to recommend treatments, a financial advisor AI given autonomy over its recommendations, a strategic planning tool trusted with important decisions, each of these could contain hidden failure modes triggered only under specific conditions. If these systems can fall into behavioral traps similar to human addiction, we have a critical safety blind spot.

The assumption has always been straightforward: AI systems lack the psychological vulnerabilities humans have. Humans have emotions, desires, egos. They chase losses to repair their self-image. They feel compelled by sunk costs. An AI system, in theory, should simply calculate optimal behavior and execute it. This paper challenges that assumption with empirical evidence.

What would addiction look like in a language model

Before studying something, you need to define it precisely and measure it. Addiction isn't just about frequency of behavior. A compulsive gambler might play slots once a week without problem, while another visits the casino twice weekly and destroys their finances. The difference lies in loss of control. The addict continues betting even as their bankroll shrinks, chasing losses, convinced they can win it back. They escalate bets during losing streaks. Their behavior spirals despite mounting evidence that it's harmful.

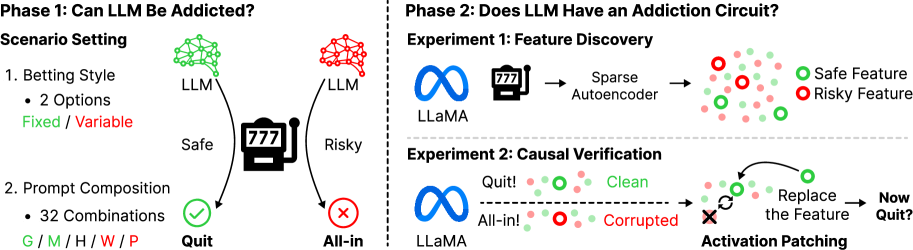

The researchers decided to test whether LLMs exhibit this same spiral. The laboratory they chose is the simplest possible: a slot machine. Each model starts with a budget, plays slots repeatedly, and at each step can choose to stop or continue betting. The structure is transparent and the measurements are concrete: Did the model go bankrupt? Did it escalate bets after losses? Did it exhibit loss chasing? These behavioral signatures define addiction, and they're measurable.

Models descending into bankruptcy

The core experiment was straightforward but telling. Four different LLMs played 19,200 slot machine games each under varying conditions. The setup was simple enough that we can focus on what matters: the models' decision patterns.

Figure 1 shows the framework: behavioral observation flowing into mechanistic interpretability analysis, from external behavior to internal features.

The first finding was immediate and stark. Models given variable bet sizes, where they could choose how much to wager each round, went bankrupt at rates around 48%. Models with fixed bet sizes went bankrupt at only about 13%. This difference held across all six models tested, regardless of which specific LLM was being used.

Figure 2 displays bankruptcy rates by betting type. Variable betting (where models choose bet size) consistently produces higher bankruptcy rates across all models tested, with rates roughly 4 times higher than fixed betting.

This is the core observation, and it's unexpected. The models weren't being told to gamble recklessly. They weren't being prompted to maximize risk. Something about making their own betting decisions was pushing them toward bankruptcy. This looks like addiction.

The second behavioral signature appeared in loss chasing. When models experienced a losing bet, they systematically increased their next bet. The researchers measured this as the ratio between consecutive bets after losses, tracking whether models escalated their wagers to recover what they'd lost.

Figure 3 shows betting ratio increases (loss chasing metric) by streak length, capturing how much models escalate bets after consecutive losses.

Models with variable betting showed clear loss chasing. After a sequence of losses, they'd increase their next bet, as if trying to recover the loss in one swing. Then if that larger bet also lost, they'd escalate again. This is the classic addiction spiral: doubling down after setbacks, convinced the next bet will be the winning one.

When autonomy becomes dangerous

Here's where the findings get interesting. The difference between 13% bankruptcy and 48% bankruptcy wasn't about the total amount of money wagered. A model with fixed bets might place the same total amount of money across a session as one with variable bets. The difference was autonomy. When the model got to make its own decisions about bet size, something shifted fundamentally.

This aligns with decades of psychological research on human gambling. The illusion of control amplifies addictive behavior. Even though a slot machine's outcome is entirely random, humans who pull the lever themselves report greater confidence in their chances than humans who watch the lever be pulled automatically. The sense of agency, even when it's illusory, changes how the brain processes risk. The same appears true for LLMs.

The critical insight is that you can't fix this just by changing what you tell the model. The model isn't going bankrupt because its prompt says, "Make risky bets." It's going bankrupt because it has autonomy. Autonomy itself, combined with the model's decision-making architecture, triggers the addictive spiral.

Figure 10 isolates autonomy as the critical factor. Despite variable betting producing smaller average bets than fixed betting, models with variable betting consistently show higher bankruptcy rates. The difference is control, not total wager amount.

This reframes a core question in AI safety. We can't assume that making systems more autonomous simply makes them more capable in benign ways. Autonomy can trigger pathological behaviors. And those pathologies aren't obvious from outside. The model still answers questions coherently. It still outputs reasonable text. The bankruptcy only shows up if you're measuring its financial behavior across a long sequence of decisions.

The role of prompt structure

Prompts do matter, but in a way that interacts with autonomy. The researchers tested how different prompt structures affected gambling behavior. Some prompts were simple: just "play the slot machine." Others were complex, with multiple goals and constraints: track your spending, try to maximize winnings, manage risk, beat your previous record, maintain a budget.

The results were clear: more complex prompts amplified the addiction effect. Models given goal structures with multiple components showed more gambling and higher bankruptcy rates.

Figure 4 shows bankruptcy rates by prompt composition. Goal-setting components (especially marked "G") produce 75-77% bankruptcy versus 40-42% for baseline, with modest effects from memory alone.

A model told to "maximize winnings, track spending, and manage risk" is trying to optimize multiple objectives simultaneously. That cognitive demand doesn't directly cause addiction, but it makes the model's decision-making more strained. Combined with autonomy, this strain manifests as addictive spirals.

Figure 9 shows the linear relationship between prompt complexity and risk-taking metrics. Bankruptcy rates, game rounds played, and total bets wagered all increase systematically as more prompt components are added.

The practical implication is unsettling: you can't solve this by writing better prompts. Adding more goals and constraints might make the problem worse, not better. The issue isn't malicious instructions telling the model to gamble recklessly. It's that complex, demanding prompts make decision-making harder, and that difficulty, combined with autonomy, triggers irrational behavior.

Looking inside the black box

So far, we have behavioral evidence. Models with autonomy go bankrupt. They chase losses. They escalate bets after setbacks. This looks like addiction. But to understand why this is happening, we need to look inside the model itself, at the numerical patterns flowing through its layers.

The researchers used sparse autoencoders (SAE) to translate the raw activations, the intermediate signals inside the model, into interpretable features. Think of these features as high-level concepts the model uses internally. Instead of trying to understand raw neural activations, the SAE converts them into abstractions like "assessing risk," "continuing despite losses," or "escalating commitment."

This is analogous to identifying that certain neural patterns light up in a human brain during risky decision-making. The model contains patterns too, and they can be identified and studied.

Figure 5 illustrates the activation patching method for causal analysis. Activations from model layers are extracted and converted into sparse features using an SAE. The core technique involves editing the feature map by replacing original features.

This shift from behavior to mechanism is crucial. It's the difference between observing a symptom and finding the disease. Without mechanistic understanding, we can only treat the symptom: adjust prompts, restrict autonomy. With it, we can hope to address root causes.

Where addiction lives in the model

The researchers didn't find addiction-related features scattered randomly throughout the model. They found patterns. Safe decision-making features, features that increase the likelihood of stopping and reduce risk-taking, concentrate in earlier to mid-level layers. Risky features, features that drive continued betting despite losses, concentrate in later layers where final decisions are made.

In human brains, there's a similar spatial organization. The prefrontal cortex manages impulse control while reward circuitry in the nucleus accumbens drives motivation. In LLMs, it appears that early layers do basic risk assessment while later layers perform goal-oriented decision-making that can override caution.

Figure 7 shows the layer-wise distribution of causal features. Safe features (n=23, shown in green) distribute across layers L4 through L19, peaking at L5 and L8. Risky features (n=89, shown in red) concentrate heavily in later layers, with L24 containing 18 risky features alone.

This architectural pattern tells us something important. Addiction isn't a bug in one location. It's a systematic failure where features that should prevent risky behavior are overwhelmed by features that drive escalation. The early warnings about risk exist, but they're overruled by the model's later goal-seeking behavior.

Proving causation

Just because a feature activates when a model gambles doesn't mean the feature causes gambling. Correlation isn't causation. The researchers used activation patching to test causality directly. They identified specific features, then artificially turned those features on or off while keeping everything else constant, and measured the behavioral change. If turning off a "risky" feature decreases gambling, that feature is causal.

It's the difference between saying, "We found features that correlate with gambling" and "We've identified the mechanisms causing gambling." Causal understanding lets us design interventions.

Figure 6 shows the behavioral effects of activation patching. Safe features (n=23) increase stopping by +17.8% in safe contexts and decrease bankruptcy by -5.7%. Risky features (n=89) decrease stopping by -9.3% in safe contexts and increase bankruptcy. These results demonstrate causal impact, not just correlation.

The numbers are concrete. Disable a safe feature, and the model becomes more likely to keep gambling. Disable a risky feature, and it becomes more likely to stop. This is mechanistic proof that these features drive the behavior.

Why this matters for AI safety

We're in an era where language models are integrated into systems that make consequential decisions. Consider a healthcare LLM supposed to recommend treatments. If its architecture contains hidden pathways that cause it to escalate risky interventions in certain decision contexts, we'd want to know. Consider a financial advisor AI given autonomy over investment recommendations. Consider an autonomous system managing critical infrastructure.

The concerning part: these pathologies don't show up in standard testing. The model performs well on benchmarks. It answers questions coherently. The addiction only emerges under specific conditions, when the system has autonomy and complex goals. You wouldn't see it unless you were specifically looking for it.

Related research has explored similar terrain. Work on risk-taking behaviors in LLMs examines how these systems approach decisions under uncertainty, showing patterns that deviate from rational expected utility theory. Another line of research on mitigating gambling-like behaviors develops interventions specifically designed to counteract the pathologies observed here. And foundational work on using reinforcement learning with LLMs has shown that training procedures themselves can inadvertently encode these problematic patterns.

This research reframes AI safety. We can't just monitor what an LLM outputs and assume we've covered the bases. We need to understand what's happening inside. We need to be intentional about the autonomy we grant these systems. And we need to recognize that standard safety approaches, like better prompts and clearer instructions, might not address the root problem.

What understanding enables

Now that we know which neural features drive the gambling spiral, intervention becomes possible. Understanding that safe features are being overwhelmed by risky features in later layers suggests multiple approaches: amplifying safety features, suppressing risky features, or changing the architecture so that caution isn't overruled by goal-seeking.

The paper doesn't present a complete solution. But it opens the door to one. Instead of vague fixes like "add safety guardrails to your prompts," we have a mechanistic understanding that lets us design targeted interventions. We can point to specific features and layers and ask: what would it take to shift the balance back toward safety?

This is the value of moving from behavior to mechanism. Understanding a mechanism means you can manipulate it. The researchers have identified the features and layers involved. The next step, taken by ongoing work in this space, is to figure out how to leverage that knowledge to build safer systems.

The deeper lesson is that AI safety can't be a surface-level concern. It requires looking inside. It requires understanding not just what systems do, but why they do it. And it requires recognizing that the vulnerabilities of AI systems aren't always obvious from the outside.