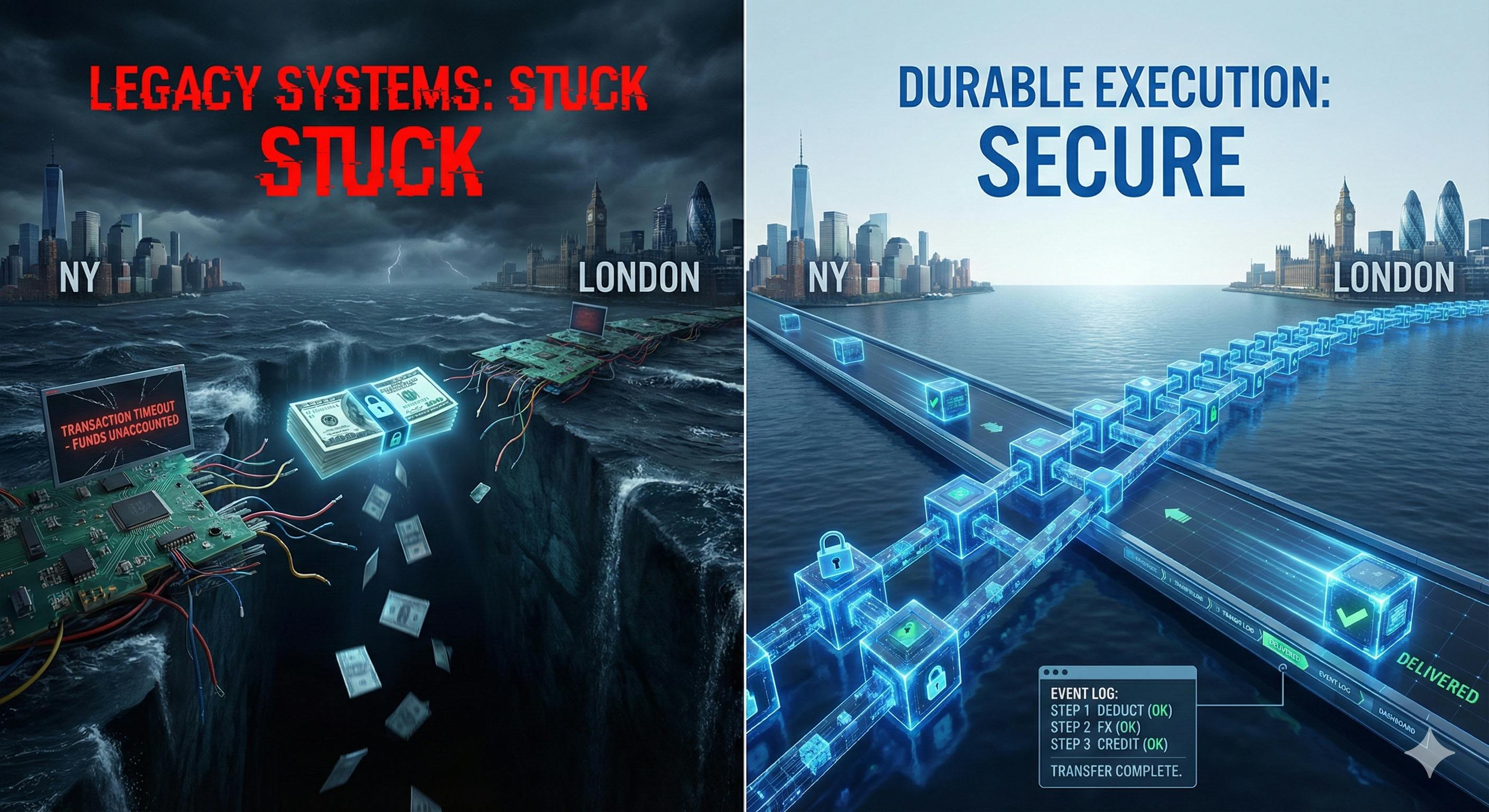

Picture yourself transferring $1,000 from New York to London. Your bank removes the funds from your account. A currency exchange service locks in the rate. The UK bank should receive the money.

The exchange service crashes after your money leaves but before it arrives. Your funds have left your account but haven't been credited elsewhere, so they are effectively stuck.

Modern payment systems settle in seconds, so this failure can make transactions irretrievable and force reconciliation teams to hunt for missing transfers. Manual reconciliation fails at a scale of one million transactions per hour. And lost money drains customer confidence

What we've used — and why some of those are not great

Building distributed payment systems has always meant picking between a few key design choices.

Two-Phase Commit (2PC)

Two-phase commit locks all databases until every participant completes, making it a blocking protocol that doesn't scale. If the UK bank's API times out, your US bank's database remains blocked until the timeout resolves. I've seen entire production systems come to a standstill because one service started taking 500ms slower than normal. The maintenance burden increases as the number of interdependent steps grows.

Manual Sagas

The most reliable approach requires writing code for every failure case. If step B fails, execute the compensation (rollback) for step A—safe but painfully slow, which means you must maintain compensation logic for every operation: change an API call and you must update its rollback; miss an edge case and you risk data inconsistencies and overwhelmed support.

If the UK bank's API times out, your US bank's database remains blocked until the timeout resolves. I have seen systems halt because a service ran 500 milliseconds slower than expected. Maintenance work increases with each added dependent step.

Durable execution

Durable execution maintains progress so tasks can continue without repeating work, and the platform handles state, retries, and recovery—reducing custom retry and error handling. This fixes the main problems with the other two approaches without sacrificing safety.

How durable execution actually works

Durable execution records every function call, API response, and decision in an append-only event log before proceeding.

Event log structure

It records an event scheduling deduct_usd(account, 1000), runs the activity, and then records a completion event {id: "evt_002", type: "ActivityCompleted", result: "success"}.

If the server crashes, the system checks the logs when it restarts. Because deduct_usd already ran, the system skips re-running it, uses the stored result, and then continues at get_fx_rate.

Activities vs. workflows

Workflows are deterministic and replayable; activities are the side-effecting operations they call (sending emails, calling APIs, writing to a database). Since activities can fail or return different results, the framework records their outcomes and activities should be idempotent.

When you call an activity from a workflow, the framework executes the side effect and records the result. Activities must be idempotent. If deduct_usd is invoked twice, it must not deduct the same amount twice. The framework guarantees at least once execution, but your code has to handle duplicates.

Idempotency

Create a distinct identifier based on the workflow execution ID and activity sequence number when scheduling an activity. If the ID already exists, deliver the stored outcome; otherwise execute the activity and save the outcome under that ID.

State persistence and replay

When the workflow reaches await execute_activity(deduct_usd), the framework checks the log, sees this completed, and returns the stored result without a network call.

The workflow repeats but side effects occur only once. The workflow advances in chunks: it executes until the next activity, then saves its state, waits for the result, and repeats.

The determinism requirement

Do not call DateTime.now(), random(), or other non-deterministic functions within workflows.

The system cannot reconcile differences during replay because values differ and the workflow history will not match. Your workflow history says "at timestamp X, we did Y," but during replay at timestamp Z, the code takes a different path.

workflow.current_time() returns the timestamp recorded in the log, so replaying a workflow yields that logged time rather than the actual current time.

Versioning

What happens if you deploy new workflow code while existing workflows are still running?

Active workflows remain on the code version they started with (for example, v2), while new workflows run the updated version. You can also use a feature flag in the workflow logic: if workflow.version >= 2 then use_new_logic(). The workflow stores the version number to ensure consistent replay.

There are two main approaches, each with different trade-offs

Orchestrator model: Temporal/Cadence

The orchestrator keeps workflow history and state in Cassandra or PostgreSQL; each execution is recorded as a database row, while workers run business logic and send back results.

Workers poll: "Any work for me?" Orchestrator responds: "Execute this activity with these parameters." Worker executes, reports back. Orchestrator logs the result and determines the next step.

Scale to millions of concurrent workflows and the orchestrator becomes the bottleneck. You write multiple events per workflow execution. A three-step workflow means 6+ database writes. Temporal uses Cassandra and sharded PostgreSQL because both are easier to scale for writes.

Database-native model—DBOS/Postgres backend

More and more developers favor the database-native model because it writes directly to PostgreSQL and reduces orchestration.

A library wrapper saves each async function's state—including local variables and execution position—to a Postgres table after every await.

Your function gets transformed under the hood. Each await becomes a checkpoint. The library serializes your function's stack frame and stores it. On restart, it deserializes and resumes.

Simpler architecture, but you're loading your database with workflow state. For high-throughput systems, you need careful capacity planning. Your database handles both transactional data and workflow checkpoints.

Regardless of which approach you choose, there's one constraint that applies to all durable execution systems: determinism.

Code Example

Here's a cross-border transfer with Temporal's Python SDK:

from temporalio import workflow

@workflow.defn

class TransferWorkflow:

@workflow.run

async def run(self, transfer: TransferDetails) -> str:

# Step 1: Deduct funds from US account

await workflow.execute_activity(

deduct_usd,

transfer,

start_to_close_timeout=timedelta(seconds=30),

retry_policy=RetryPolicy(maximum_attempts=3)

)

# Step 2: Get current exchange rate

rate = await workflow.execute_activity(

get_fx_rate,

"USD_GBP",

start_to_close_timeout=timedelta(seconds=10)

)

# Step 3: Credit UK account with converted amount

await workflow.execute_activity(

credit_gbp,

CreditRequest(

account=transfer.recipient,

amount=transfer.amount * rate

),

start_to_close_timeout=timedelta(minutes=5),

retry_policy=RetryPolicy(

maximum_attempts=100,

initial_interval=timedelta(seconds=1),

maximum_interval=timedelta(hours=1)

)

)

return "Transfer complete"

Look at the retry policies. If credit_gbp fails, it retries with exponential backoff for up to 100 attempts over hours. Your workflow remains persisted while waiting; it does not hold threads or lock connections.

Picking your tools

Temporal (Go/Java) fits enterprises running millions of workflows—it requires dedicated platform teams and infrastructure investment to scale reliably. DBOS and Inngest are better for small teams that prioritize speed and low operational cost.

DBOS and Inngest are more practical for smaller teams and rapidly moving companies. These tools are compatible with Postgres, Node, and Python, so you can get started in days instead of weeks. You are on the hook for less operational overhead, which matters when you are still finding product-market fit.

Durable Functions is tightly integrated with Azure and stands out for Azure users, though it does lock you into Microsoft's ecosystem.

Conclusion

Choosing the right infrastructure matters more than complex error handling when constructing dependable distributed systems. Durable execution frameworks remove complete classes of problems—such as retry logic, state management, and partial failure recovery—by handling them at the infrastructure layer.

In many cases, the code you do not write can outweigh the value of the code you write. A platform that guarantees effectively exactly-once execution and automates recovery lets you focus on business logic instead of failure handling.