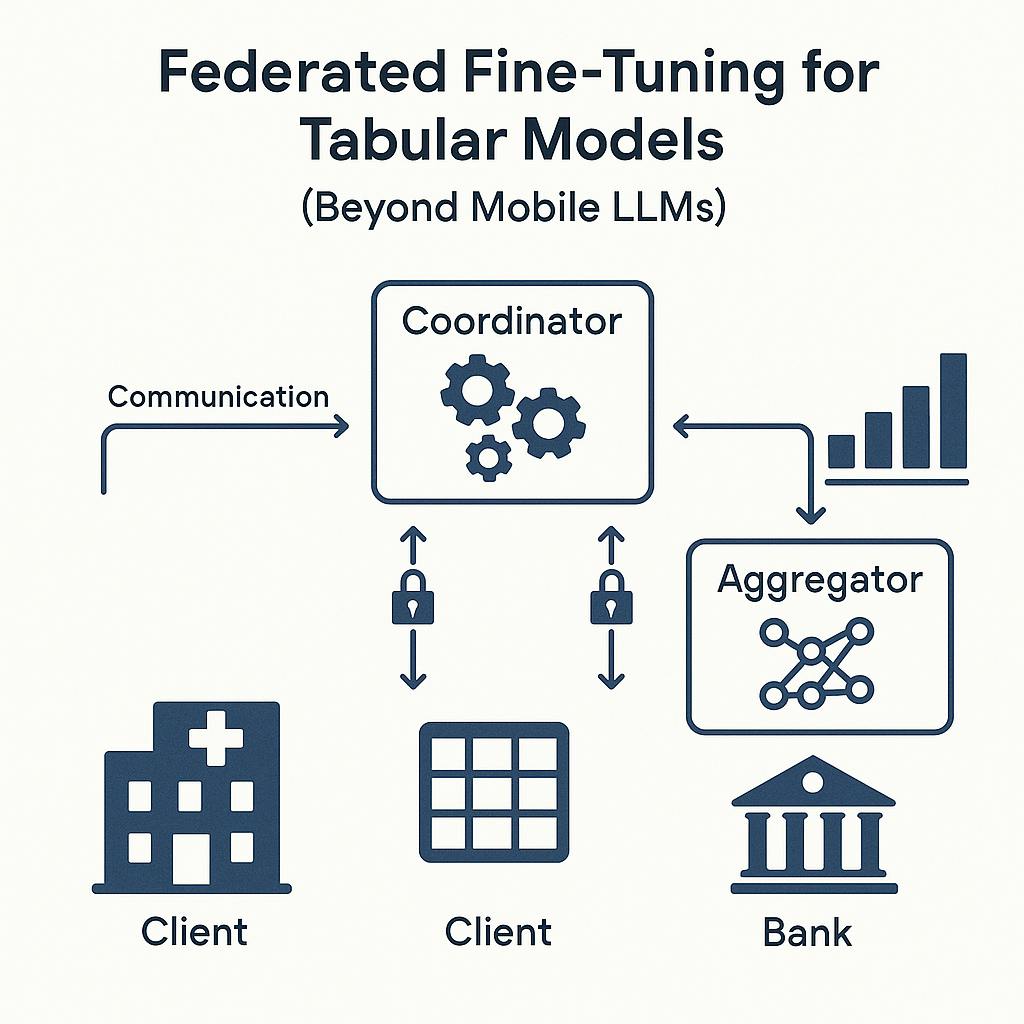

In regulated domains like healthcare and financial services, data cannot leave the institution, yet models must learn from distributed, highly skewed tabular datasets. A pragmatic federated setup has three moving parts: a coordinator (orchestrates rounds, tracks metadata, enforces policy), many clients (hospitals, banks, branches, labs) that compute updates locally, and an aggregator (often co-located with the coordinator) that produces the global model. Communication proceeds in synchronous rounds: the coordinator selects a client subset, ships the current model snapshot, clients fine-tune on local tables, and send updates for aggregation. All communication must be mutually authenticated (mTLS), signed (to prevent replay), and rate-limited. Key management belongs to the platform, not the application: rotate transport and encryption keys independently; tie model-update keys to enrollment of each client.

The threat model should be explicit before a line of code ships. Most hospital/fintech deployments assume an honest-but-curious aggregator: the server follows the protocol but may try to infer client data from updates. Some partners might be Byzantine (malicious) and send crafted updates to poison the model or leak others’ data through gradient surgery. External adversaries can attempt membership inference or reconstruction from released models. On the client side, data provenance varies—coding systems (ICD, CPT), event timestamps, missingness patterns—and these heterogeneities become side channels if not normalized. Policy decisions flow from the model: if the aggregator is trusted only to coordinate but not to view individual updates, you will need secure aggregation; if insider threats are plausible at clients, you will need attestation (TPM/TEE) and signed data pipelines; if model publishing is required, you should budget for differential privacy to bound inference attacks on the final weights. Define what is logged (e.g., participation, schema fingerprint, update norms) and what is never logged (raw features, row counts per label) to keep auditability without leakage.

Federated Pipelines for XGBoost and TabNet

Tree ensembles and neural tabular models federate differently, but both can be made practical with the right abstractions.

For XGBoost, the core questions are data partitioning and how to hide split statistics. In horizontal federation (each client owns different rows with the same feature schema), clients compute gradient/hessian histograms locally for their shards; the aggregator sums histograms and chooses splits globally. In vertical federation (each client holds different features for the same individuals), parties jointly compute split gains via privacy-preserving protocols keyed on a shared entity index—more complex and often requiring secure enclaves or cryptographic primitives. To federate fine-tuning, start from a pre-trained ensemble (e.g., trained in one compliant sandbox or on synthetic data). In each round, allow clients to add a small number of trees or adjust leaf weights using local gradients. Constrain depth, learning rate, and number of added trees per round to prevent overfitting to any site and to cap communication size. When class imbalance differs by site, use per-client instance weighting and share only normalized histogram buckets; this keeps the global split decisions representative while preserving privacy.

For TabNet (or similar neural tabular architectures), classical FedAvg works: distribute weights, train locally for a few epochs with early stopping, then average. TabNet’s sequential attention and sparsity regularizer are sensitive to learning-rate schedules; use a lower client LR than centralized baselines, apply server-side optimizers (FedAdam or FedYogi) to stabilize across heterogeneous sites, and freeze embeddings for high-cardinality categorical features during the first rounds to minimize drift. Mixed precision is safe if all clients use deterministic kernels; otherwise, floating-point nondeterminism introduces variance in the averaged model. For schema drift—new categorical levels at a client—reserve “unknown” buckets and enforce a registry of categorical vocabularies so that embeddings align across sites. When clients have wildly different dataset sizes, sample clients with probability proportional to the square root of their rows to balance variance and fairness, and cap local epoch counts so that small sites don’t get drowned out.

Two system choices improve practicality. First, add proximal regularization at clients (FedProx) to discourage local steps from straying too far from the global weights; this reduces the damage from non-IID feature distributions. Second, ship selector masks or feature-importance summaries from the global model back to clients to prune useless columns locally, cutting I/O and attack surface. In both pipelines, unit-test the serialization of model state and optimizer moments so that upgrades don’t invalidate resuming a paused federation.

Federated Averaging vs. Secure Aggregation vs. Differential Privacy

Federated averaging (FedAvg) alone protects data locality but does not hide individual updates. If your aggregator is honest-but-curious, secure aggregation is the baseline: clients mask their updates with pairwise one-time pads (or via additively homomorphic encryption), so the server only learns the sum of updates when a threshold of clients participates. This prevents the coordinator from inspecting any one hospital’s gradient histogram or weight delta. The trade-offs are engineering and liveness: you need dropout-resilient protocols, late-client handling, and mask-recovery procedures; rounds may stall if too many clients fail, so implement adaptive thresholds and partial unmasking only when it cannot deanonymize any participant. For XGBoost histograms, secure aggregation composes well because addition is the main operation; for TabNet, the same masking applies to weight tensors but increases compute and memory overhead modestly.

Differential privacy (DP) addresses a different risk: what an attacker can infer from the published global model. In central DP, you add calibrated noise to the aggregated update at the server (post–secure aggregation), and track a privacy budget ((\varepsilon, \delta)) across rounds using a moments accountant. In local DP, each client perturbs its own update before secure aggregation; this is stronger but typically harms utility more on tabular tasks. For hospital/fintech use, central DP with clipping (per-client update norm bound) plus secure aggregation is the sweet spot: the server never sees raw updates, and the public model carries a quantifiable privacy guarantee. Expect to tune three dials together—clip norm, noise multiplier, and client fraction per round—to keep convergence stable. For XGBoost, DP can be applied to histogram counts (adding noise to bucket sums and gains) and to leaf-weight updates; small trees and shallower depth compensate for DP noise. For TabNet, DP-SGD with per-sample clipping is standard but costly; a practical compromise is per-batch clipping at clients with conservative accounting, accepting a slightly looser bound for substantial speedups.

In short: FedAvg is necessary for locality, secure aggregation is necessary for update confidentiality, and DP is necessary for release-time guarantees. Many regulated deployments use all three: FedAvg for orchestration, secure aggregation for transport-time privacy, and central DP for model-level privacy.

What to Monitor: Drift, Participation Bias, and Audit Trails

Monitoring makes the difference between a compliant demo and a safe, useful system. Begin with data and concept drift. On the client side, compute lightweight, privacy-preserving sketches—feature means and variances, categorical frequency hashes, PSI/Wasserstein approximations over calibrated summary stats—and report only aggregated or DP-noised summaries to the coordinator. On the server, track global validation metrics on a held-out, policy-approved dataset; split metrics by synthetic cohorts that reflect known heterogeneity (age groups, risk bands, device types) without exposing real client distributions. For TabNet, watch sparsity loss and mask entropy; sudden changes imply the model has relearned which features to attend to, often due to schema shifts. For XGBoost, track tree-additions per round and leaf-weight drift; spikes can indicate local overfitting or poisoned histograms.

Participation bias is the silent model killer in federated tabular settings. If only large urban hospitals or high-asset branches come online consistently, the global model will overfit to those populations. Log, at the coordinator, the distribution of active clients per round, weighted by estimated sample sizes, and maintain fairness dashboards with per-client (or per-region) contribution ratios. Apply corrective sampling in future rounds—oversample persistently underrepresented clients—and, when feasible, reweight updates by estimated data volume under secure aggregation (share volume buckets rather than exact counts). For highly skewed tasks, maintain multiple regional or cluster-specific models and a lightweight router; this can outperform a single global model while staying within compliance.

Audit trails must be first-class. Every round should produce a signed record that includes model version, client selection set (pseudonymous IDs), protocol version, secure-aggregation parameters, DP accountant state ((\varepsilon, \delta)), clipping thresholds, and aggregated monitoring sketches. Store hashes of model checkpoints and link them to the round metadata so that you can reconstruct the exact training path. Retain a tamper-evident log (append-only or externally notarized) for regulator review. For incident response, implement automatic halts when invariants break: sample-ratio mismatch in client selection, unexpected schema fingerprints, norm-clipping saturation (too many updates hitting the clip), or drift beyond control limits. When a halt triggers, the system should freeze the global model, page the on-call, and expose the round metadata needed for forensics without revealing any client’s raw statistics.

Finally, make model updates safe by default. Enforce differential release channels: internal models can skip DP noise if they never leave the enclave, while externally shared models require DP accounting. Require human approval for schema changes and feature additions; in tabular domains, a “just one more column” habit is how privacy leaks creep in. Provide clients with a dry-run mode that validates schemas, computes sketches, and estimates compute cost without contributing updates—this reduces failed rounds and guards against silent data issues. And document the threat model, privacy budgets, and monitoring policies alongside the model card so downstream users understand both capabilities and limits.

Takeaway

For tabular data in hospitals and fintech, practicality comes from layering defenses. Use federated averaging to keep rows in place, secure aggregation to hide any one site’s contribution, and differential privacy to bound what the final model can leak. Wrap those choices in pipelines that respect tabular peculiarities—histogram sharing for XGBoost, stabilizers for TabNet—and watch the system like a hawk for drift and skew. Do this, and you can fine-tune models across institutions without the data ever crossing the wire, while still delivering accuracy and an audit story that stands up to regulators.