Federated learning is often presented as the answer to privacy-preserving AI: train collaboratively without sharing data. The idea is elegant, and in many cases, correct.

But federated systems quietly depend on something far more fragile—synthetic data. If that data is low-quality, poorly governed, or subtly leaking private information, the entire architecture fails, regardless of how carefully models are distributed.

The real risk in privacy-preserving AI isn’t where models run. It’s how synthetic data is generated, monitored, and controlled.

1. The Architect’s Dilemma: Privacy Without Garbage Data

The industry is rightly excited about privacy-preserving techniques like federated learning. The promise is compelling: build shared business capabilities—such as fraud detection in payments—without ever exchanging sensitive customer data.

But there’s an uncomfortable dependency hiding beneath this vision.

Most federated or privacy-first systems assume the existence of high-quality synthetic data—either for local model training or for controlled sharing. If that synthetic data is low-quality, stale, or poorly governed, the entire system collapses.

This becomes a classic garbage-in, garbage-out problem—with a privacy twist:

- Bad synthetic data → ineffective business models (e.g., fraud detection models or auto-repair models for higher straight-through processing)

- Overly realistic synthetic data → PII leakage

The engine that produces this data is usually a GAN—and it is both the most important and the most dangerous component in the stack.

2. Why GANs Matter (and Why Simple Masking Fails)

Not all “fake data” is valid.

GANs work because they don’t simply scramble or anonymize records. They learn the underlying statistical distribution of real data.

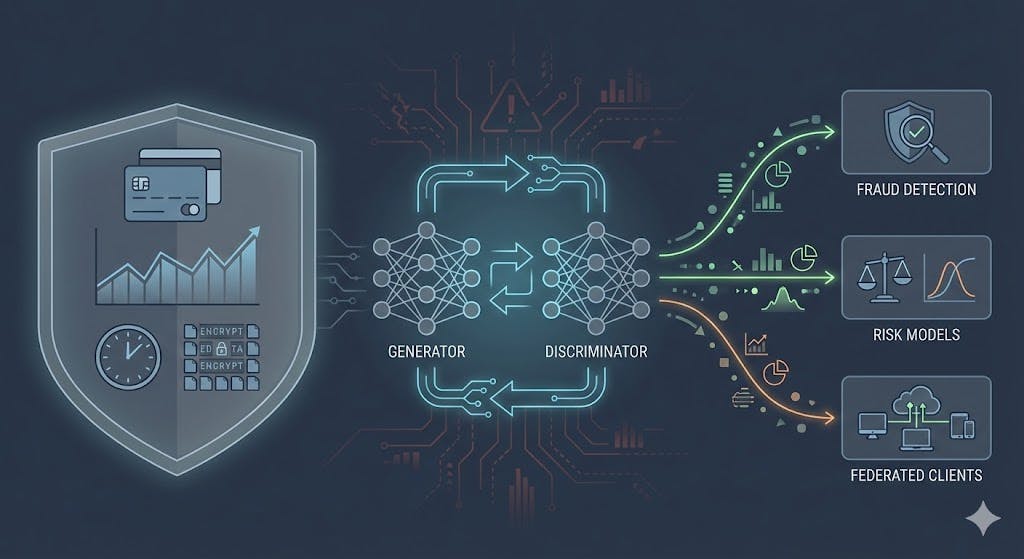

A GAN consists of two competing models:

- A Generator that produces synthetic samples

- A Discriminator that tries to distinguish real data from fake

Through this adversarial process, the generator learns to produce data that is statistically indistinguishable from real transactions.

For fraud detection, this distinction is critical. A good GAN doesn’t just create a fake $100 transaction—it establishes:

- Realistic transaction sequences

- Time-of-day effects

- Merchant category correlations

- Behavioral fraud patterns

This is what makes synthetic data mathematically sound, not merely privacy-safe.

3. The Hidden Problem: Privacy vs Utili

Synthetic data lives on a knife-edge:

- Too fake → models miss real fraud

- Too real → the GAN memorizes training data

And this balance is never static:

- Transaction behavior shifts daily

- Fraud patterns evolve continuously

- Models degrade silently over time

This turns synthetic data into an ongoing MLOps problem rather than a one-time preprocessing step.

On the utility side, GANs suffer from a well-known failure mode called mode collapse. This occurs when the generator discovers a small set of outputs that reliably fool the discriminator—and keeps producing only those—while ignoring the full diversity of the real data.

In fraud detection, this is especially dangerous. Rare but critical fraud patterns are often the first “modes” to disappear, leading to models that perform well in testing but fail in production.

4. The “GAN Factory” Mental Model

To reason about this correctly, it helps to think of synthetic data generation as a factory—not a script.

A secure GAN pipeline has three distinct layers:

- Secure training (where real data exists)

- Controlled inference (where synthetic data is generated)

- Continuous monitoring (where risk is managed)

Each layer has different threat models and responsibilities.

5. Layer 1: Training the GAN in a Clean Room

There’s no escaping this rule:

GANs must be trained on real, PII-laden data.

That training must happen inside a hardened environment:

- No public internet access

- Strict network boundaries

- Encrypted storage and compute

- Minimal export permissions

The key architectural idea is this:

The only artifact allowed to leave the clean room is the trained generator model—not the data.

That generator is an abstraction. It encodes statistical behavior, not individual records. However, statistical abstraction alone is not a formal privacy guarantee.

In practice, standard GANs can overfit—effectively memorizing rare or unique transactions—making them vulnerable to Membership Inference Attacks.

To mathematically cap information leakage, the training process itself must be privacy-aware. This is where Differential Privacy (DP) comes in. By introducing calibrated noise during training (for example, via DP-SGD), we can place an explicit upper bound on how much information about any single transaction the model can learn—or leak.

Synthetic data is only meaningfully private when the generator is trained with formal privacy guarantees, not just good intentions.

6. Layer 2: Synthetic Data as an API

Once trained, the generator becomes infrastructure.

Instead of sharing datasets, organizations expose a synthetic data service:

- “Generate N synthetic transactions.”

- “Simulate last week’s behavioral patterns.”

- “Produce fraud-heavy samples for training.”

Producing targeted samples—such as fraud-heavy or merchant-specific data—requires more than a vanilla GAN. In practice, this is achieved using a Conditional GAN (cGAN), where class labels or control variables (e.g., fraud = true) are fed into both the generator and discriminator.

This allows the API to control what kind of synthetic data is produced, not just how much, while preserving the same privacy and isolation guarantees.

The result is a clean decoupling of data access from data usage. Downstream systems never touch real PII—only model-generated abstractions of it.

You don’t share data. You share the ability to generate data.

7. Layer 3: Monitoring the Privacy–Utility Trade-Off

This is the hardest part—and the one most systems ignore.

Utility Drift

Synthetic data slowly stops matching real behavior:

- Transaction distributions shift

- Temporal patterns break

- Fraud recall drops silently

This requires continuous statistical monitoring and automated retraining triggers.

Privacy Leakage

The GAN becomes too good:

- Memorizes rare transactions

- Reproduces near-duplicates

- Enables membership inference attacks

This is a catastrophic failure mode—and it often goes undetected without deliberate testing.

8. Measuring “Good” Synthetic Data

Three questions determine whether synthetic data is truly safe and sound.

Does it preserve task performance?

The gold-standard evaluation is TSTR (Train on Synthetic, Test on Real). A fraud model is trained entirely on GAN-generated data and then evaluated on real transaction data. If it still detects fraud with high recall and precision, the GAN has captured a meaningful signal—not just surface-level statistics.

Does it resist privacy attacks?

Synthetic data must be evaluated for resistance to adversarial inference. A common risk is membership inference, in which an attacker attempts to determine whether a specific real transaction was included in the training set. Success indicates memorization rather than abstraction.

Another essential check is sample uniqueness analysis, which measures how closely synthetic outputs resemble real records. Near-duplicates signal potential leakage and should trigger retraining or stronger privacy controls.

Can privacy be proven, not assumed?

Privacy should not rely solely on heuristics. Differentially private GANs introduce calibrated noise during training to mathematically bound how much any individual record can influence the model.

This enforces an explicit privacy–utility trade-off, allowing institutions to tune privacy budgets based on acceptable risk. The shift is from assuming privacy to provably enforcing it.

Synthetic data is not inherently safe. It must be governed.

9. The Uncomfortable Cost Question

There’s one question that rarely comes up in architectural conversations:

What does it cost to train and maintain high-fidelity GANs at every institution?

High-quality GANs are expensive:

- GPU-heavy

- Data-hungry

- Operationally complex

This raises deeper questions about:

- Shared privacy infrastructure

- Trusted synthetic data utilities

- Centralized engines vs decentralized ownership

10. Final Takeaway: The GAN Is the Real Trust Boundary

Federated learning gets the spotlight—but the GAN is the linchpin.

A poorly designed synthetic data pipeline doesn’t just create bad data. It creates real risk:

- Fraud blind spots

- Hidden compliance violations

- Systemic trust failures

If we want truly collaborative, privacy-preserving AI in finance, GAN MLOps must be treated with the same seriousness as payment rails, encryption, and identity systems.

The future of trust isn’t just about where models run. Federated learning may define where computation happens, but Differentially Private GANs define what data is safe to learn from.

Ultimately, trust in AI systems will be determined by how synthetic reality is manufactured, monitored, and controlled.