TL;DR

The familiar dichotomy between agile approaches that prioritise shipping software to elicit real requirements and waterfall approaches that prioritise upfront requirements engineering is overly simplistic. In between these poles, there’s an intermediate approach for developing requirements that is easy enough to implement and better at delivering value to users and stakeholders. Features and benefits of this approach include:

- Defining a process for requirements development that is iterative, produces standard and agreed upon outputs, and integrates with a broader agile delivery approach

- Leveraging cheap experiments (e.g. rapid prototyping) to get going quickly in an evidence-based way without shipping fully working software

- Using a hierarchy (usually associated with requirements engineering) to provide useful context for users and stakeholders at appropriate levels of abstraction

- Selectively populating the hierarchy (not necessarily top-down) so that the development team and others have the context they need to align and make better decisions.

Vision Coach

Vision Coach is the real-world project I’ll use as a way into this topic. It’s a platform my team built in partnership with Bayer Healthcare for patients living with, and doctors treating, an eye disease called

diabetic macular edema (DME/DMO). DME affects c.21 million people with diabetes globally and is the leading cause of blindness in adults of working age.

Bayer Healthcare provides a therapy that is one of a class of therapies that eye doctors use to improve the vision of people with retinal diseases like DME. Despite being a sight-threatening condition, patient adherence to therapy is poor, meaning vision outcomes are often suboptimal. Addressing this problem formed the focus of the project.

For ease, I've stuck with traditional terms throughout - e.g. “requirements, elicitation, specification”. Though not perfect (isn't calling hypotheses "requirements" weird?), they have the advantage of being familiar.

Requirements approach

Debates about how to do requirements often centre on two antithetical approaches that I’ll call Analysis paralysis and Iteration worship. Analysis paralysis says you must elicit and specify requirements upfront before any coding can start, they must have a perfect set of attributes (consistency, lack of ambiguity, completeness etc), and if this takes weeks or even months of effort, so be it.

Iteration worship says the opposite - the best way to elicit requirements is to build something and test it out with users. Users don’t know what they want, or at least can’t always articulate it, and it’s not until they’re presented with working software that their true requirements emerge. Upfront specification is therefore a waste of time.

Very broadly, this describes waterfall and agile approaches to requirements development. The two are opposites, and it’s usually assumed you’re on one side or the other. So which side are you on?

Well, obviously you’re not on the side of Analysis paralysis. Spending lots of time eliciting requirements from stakeholders, making them consistent, complete, testable (and all the rest) before you start coding is futile in the face of uncertainty and change, and all it does successfully is raise the cost of failure and learning.

Which is no good if you need to fail and learn a lot, like most teams. Oh, and the fact it doesn’t work is well evidenced - the

Standish Group’s Chaos survey is one source frequently wheeled out as proof.

So that means you’re on the Iteration worship side, right? Well no, at least not as it’s been characterised (or caricatured?) here. This approach has problems too. First, it’s simply not true that you can’t say anything valuable about requirements without first shipping software to users - rapid prototyping using wireframing tools is one technique capable of eliciting useful evidence for requirements before coding starts.

Second, iterations aren’t actually that cheap - sure, they’re cheaper than delivering software waterfall-style, but they’re still expensive vs. techniques like rapid prototyping.

Third, if you genuinely spend no time defining your requirements, what you build is likely to be further away from your target, necessitating more iterations to get there.

Our approach fell somewhere in between the two - some specification up front combined with shipping working software early to elicit further requirements from users in higher fidelity experiments.

Process and hierarchy

In Part 1, I identified some key properties of a requirements development process and its outputs - e.g. it needs to be collaborative, iterative, and its outputs need to be tailored to different audiences. Going beyond this, it’s helpful to define a process and identify techniques for optimising outputs.

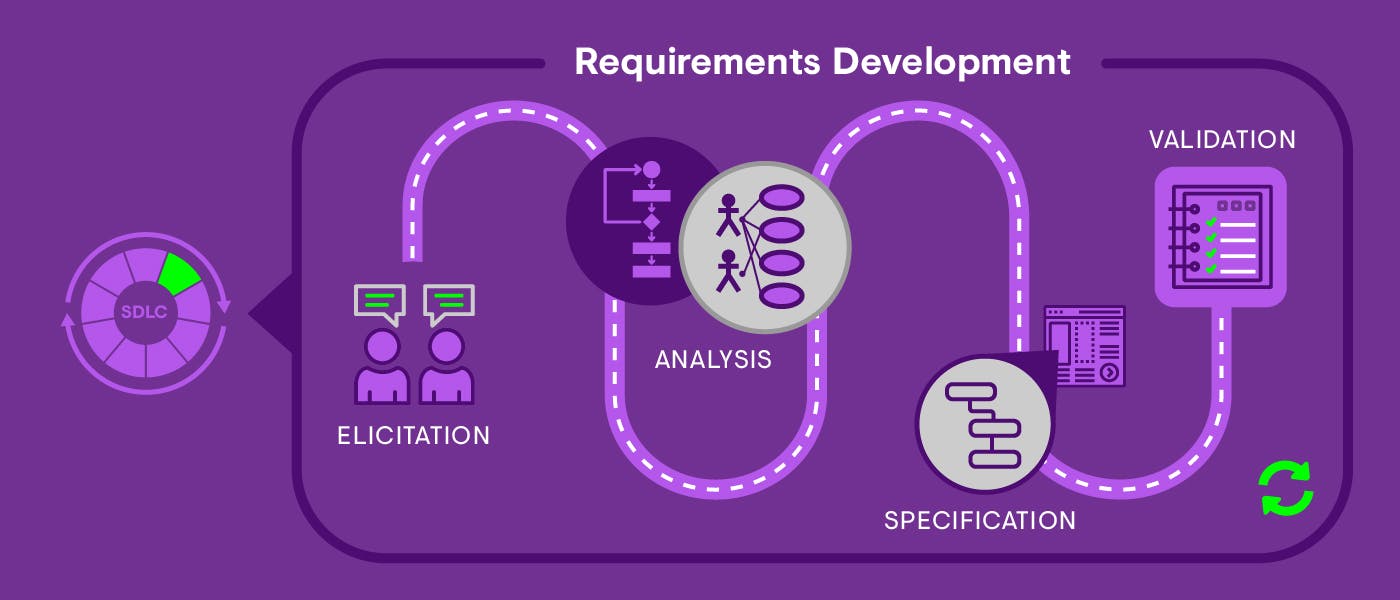

Figure 1 shows the process we followed. It consisted of four activities:

- Elicitation - Drawing requirements out of users and stakeholders using a variety of techniques

- Analysis - Understanding the underlying problems to be solved, refining user and stakeholder requirements, and combining this with system requirements

- Specification - Formulating requirements using a hierarchy and agreed templates, and documenting them

- Validation - Verifying requirements are as accurate as they can be given the evidence, and can be verified as being done once implemented.

Figure 1. Requirements development process (adapted from Wiegers & Beatty, Software Requirements, 3rd Edition).

The process was iterative and involved moving back and forth between different activities, often in the same session, meaning faster feedback loops and better outputs. It also involved a review and approval decision point for client stakeholders, which was required before any coding could start. Beyond this, it was integrated into the broader Scrum process we used to deliver the project, which consisted of 2-week sprints, daily standups, client showcases and retrospectives at the end of the sprint, and planning at the start of the next.

Additionally, we defined a hierarchy that consisted of the levels shown in Figure 2.

Why define a hierarchy? Different people need different information captured at different levels of abstraction. On Vision Coach, client stakeholders spent time reviewing the vision, scope, user stories and high-level features, but weren’t interested in technical designs or tasks.

A delivery team also needs context for decisions, which a sensible hierarchy can provide.

Figure 2. The requirements hierarchy.

Defining the hierarchy was the easy part. Populating it was more time consuming, but given we weren’t in the analysis paralysis game and had a small team, we populated only as much as we needed to upfront to get going. Initially this involved more work at the vision & scope levels to get the project greenlit, and then at the lower levels.

Importantly, we didn’t always populate the hierarchy top-down, a good example being a scope change, where we might document only a user story and tasks if it fitted with existing features and non-functional requirements and wasn’t sufficiently contentious or complex to call for technical designs.

Which is to say, we used the hierarchy more as a guide than an enforceable schema - it helped us structure requirements when we needed to produce them at the appropriate level(s) of abstraction.

Elicitation

Healthcare is complicated. There are lots of stakeholders, usually related in complex ways. These include patients, doctors, clinics, hospitals, payers, regulators… the list is extensive. Direct engagement with all of them is impractical, so you create representative proxies, which was our approach here.

Requirements and constraints (conditions placed on requirements) came from a large number of stakeholder groups. Here are the main ones (there were others!):

Users

- Patients. Patients were generally of working age (55 or older), had been living with diabetes for a number of years, and had started to develop complications like DME as their disease progressed. Direct interaction with this group was governed by strict regulations (more on this later), which made user testing more difficult than usual.

- Doctors. The doctors were ophthalmologists (specialist eye doctors) who worked with teams of other doctors, technicians and administrators in stand-alone clinics or clinics within hospitals in a mix of public and private settings.

- Clinics and hospitals. The organisation in which doctors treated patients. The larger organisations had well-developed corporate functions like IT, Clinical Governance and Information Governance, all of which had requirements.

Client functions

- Marketing. The global ophthalmology marketing team commissioned and managed the project. They had requirements related to business priorities and the use of evidence (qualitative and quantitative studies) to guide our work.

- IT. Business rules documented in policies and procedures mandated ways of working and, on occasion, use of specific technologies. Requirements covered things like design guidelines, cookies, user consent, web analytics and certificate management.

- Security. The system stores identifiable patient data, which is subject to stringent controls. Security requirements were distilled into a vendor security assessment. Separately, we received requirements for external pen testing, distributed denial of service (DDoS) protection using named suppliers and certification against the ISO27001 standard for information security.

- Compliance. Vision Coach had to go through legal, medical and regulatory (LMR) compliance review before it could be used by patients and doctors. This involved global and local review against requirements in these different domains. Reviews would usually elicit new requirements.

Client suppliers

- Translation agency. The agency translating the global english copy into 12 translated and localised versions had requirements and constraints around the technology and process used.

Us

- Delivery team. We were a small team with a number of roles: Developers, Testers, DevOps, a Technical Architect, Product Owner (PO), Project Manager, User Experience (UX), UI Design and clinical domain expert. The PO and UX leads elicited requirements.

For the client, we created a core team at the global level to represent key client functions across the business. We elicited requirements from this group, and if we needed to speak with other stakeholders (e.g. specialists in fields like medical device regulation or data privacy) this was facilitated by this team.

For patients and doctors, elicitation was more complicated, as pharma companies (and their suppliers) are bound by strict regulations and internal processes for communicating with them, meaning user testing isn’t easy, quick or cheap.

Luckily, in the first instance, we had access to clinical expertise internally, and were able to rely on extensive market research and user testing with patients of a previous similar(ish) prototype. On an ongoing basis, we elicited requirements using a mixture of observation, interviews, workshops, testing with prototypes (built to differing levels of fidelity) and ad-hoc follow up.

Analysis, specification & validation

Elicitation outputs were documented by the PO and UX lead, usually as unstructured notes in the first instance, which were played back to client stakeholders for review and approval. These were then collated by the PO and turned into user stories (Level 2 in our hierarchy) and documented in a Jira ticket using an agreed template that included:

- An agile user story in the form “As a [type of user], I want [some goal], so that [some reason]”

- Background/rationale explaining why the requirement was important

- Acceptance criteria using Gherkin’s steps syntax covering primary and alternate goals

- Links to wireframes, UI designs and other relevant artifacts.

Discussion with the internal delivery team started in backlog refinement sessions, the goal of which was to refine stories, nail down acceptance criteria, and augment them with features, non-functional requirements, technical designs and tasks (Levels 3-5).

Discussion was finished off in planning, where we compiled a sprint backlog of requirements that met our Definition of Ready. Disagreements about technical designs, often due to complexity, were the cue for further design work, which we did in design sessions during sprints.

In all these sessions the PO, with support from appropriate domain experts, represented users and client stakeholders to the developers, helping to answer their questions and guide their decisions.

This is how we specified artifacts at Levels 3-5 in our hierarchy:

- Features and non-functional requirements (NFRs; Level 3) were captured at a high-level in Jira epics, accompanied by a brief description and links to wireframes, designs etc, and were used to group related user stories. We documented NFRs as separate docs using the same approach as technical designs (see next bullet), and used acceptance criteria in our user stories to help surface them early on.

- Technical designs (Level 4) consisted of a mixture of prose and diagrams and were documented in reStructuredText and PlantUML, stored in a git repo and rendered to static html using Sphinx and the Read the Docs theme, with links to the hosted docs created in our Jira project. These days we’ve changed our docs stack pretty significantly, but the docs as code approach is still something we like a lot.

- Tasks (Level 5) were documented as subtasks of the user story parent ticket in Jira and generally took the form of lists of work in, and out of, scope. This added granularity to a story’s acceptance criteria and allowed us to verify that a story had been done (part of the validation step in our process).

Example requirements

Let’s look at a thin vertical slice of our hierarchy from onboarding for the patient mobile app to see how the outputs turned out. It includes a mix of content that applies to the platform globally as well as to patient app onboarding only.

Vision and scope (Level 1)

We used this

neat template (originally from Geoffrey Moore's

Crossing the Chasm) to capture the vision and scope succinctly:

- For patients with diabetic eye disease (target user)

- Who typically adhere poorly to therapy (statement of need or opportunity)

- The Vision Coach service (product name)

- Is a mobile app (product category)

- That provides access to key health data, help understanding it and tools to take action to improve adherence, vision outcomes and general health (key benefits)

- Unlike other apps for people with diabetes (primary competitive alternative)

- Our product addresses diabetic eye disease in addition to the underlying diabetes (statement of primary differentiation)

User stories (Level 2)

The onboarding epic collected together all the user stories for onboarding, which consisted of two separate flows - sign up and login. Figure 3 shows a screenshot of a story in both flows - SMS-based one-time password (OTP) verification. It uses the template described above, and has acceptance criteria covering both primary and alternate goals.

Figure 3. Example user story for account verification during onboarding

Features and non-functional requirements (Level 3)

Features

The onboarding feature was captured in a Jira epic as lists for the separate sign up and login flows.

Sign up:

- Confirm region and language

- Consent to terms and conditions

- Enter phone number

- Verify SMS one-time password (OTP)

- Enter user name

- Confirm treatment plan

Login:

- Enter phone number

- Verify SMS OTP

It was supplemented by the quasi activity diagram shown in Figure 4, and linked to related user stories.

Figure 4. Patient mobile app onboarding flow.

Non-functional requirements (NFRs)

- Security was important as the system stores patient data, a sensitive class of personal data as defined by GDPR. More broadly, we were required to comply with and certify against ISO27001, an industry standard for information security, part of which covers controls for user authentication. This required a lot of effort, and impacted our technical designs and implementations, as well as our processes, people and locations more broadly. Ongoing annual audits by a mutually agreed auditor also meant it wasn’t a one off.

- Internationalisation (i18n) and localisation (l10n) was important since the app was initially designed for use in 10 countries with 12 local copy sets. There was also a project requirement for all translation work to be carried out by an approved translation agency. This ended up impact process more than product.

- Legal was extremely important given the compliance requirements around patient data originating from laws, regulations, standards and contracts. Data sovereignty (the country in which data is stored) is important when dealing with patient data (both for real and perceived reasons). For Vision Coach, patient data needed to live in a number of different global regions. Consent for optional analytics data sharing captured in onboarding also needed to be stored and renewed at least annually (in line with EU law).

- Accessibility was relevant given some users were visually impaired (ranging from mild to severe). A constraint on this was the rich accessibility tooling provided natively by iOS and Android, and some evidence (admittedly in a much broader population) that these tools were frequently used by users with visual impairment (e.g. screen readers, as in the acceptance criteria in Figure 3).

- Performance & scalability were important as the system needed to respond within a minimum amount of time for it to be usable, so the way we deployed the infrastructure needed to be able to support a best case estimate of user numbers, especially where it was heavily loaded.

Technical designs (Level 4)

- Authentication. Figure 5 shows a UML sequence diagram for the broad authentication flow, including phone number verification using an SMS-based OTP. We didn't produce many sequence diagrams for the app, but the authentication flow was one area where we did, in this instance because there was disagreement on the technical design. Disagreement and complexity were normally our triggers for doing more work in technical design sessions, as mentioned, and sequence and other diagrams were occasionally outputs of these, when deemed useful for analysing requirements and improving team alignment.

Figure 5. UML sequence diagram showing the end-to-end authentication flow

- I18n and l10n. Since translation work was done by an external agency, translated content needed to be in a form that was easy to move back and forth during the process. We decided to use a common framework for the various apps that made up Vision Coach. All of the content was stored in yaml files, which were factored out of any individual application and loaded at runtime. For the patient app, on start up the app loads content from a translation API.

- User consent. Users are asked for consent to track application usage as part of the terms of service consent. We needed to record the consent event and send it to a third-party API specified by IT stakeholders at the client. Consent information then needed to be made available to multiple applications and devices, which was was done through data stored in the authenticated API in the case of the patient app.

- SMS services. We chose to use Amazon Web Service’s (AWS) Simple Notification Service (SNS) for sending transactional SMS messages. This was a decision of convenience, given the application was hosted on AWS.

- Regional deployment. Due to the requirement of keeping patient data within certain regions, we needed to deploy the platform to multiple AWS regions. This gave the added advantage of improving latency for global customers. Only one version of the patient app was needed and we used a single global endpoint well known to allow it to discover regional resources such as APIs and authentication services. Figure 6 shows the regional deployment. It includes one primary region (EU) that hosts static services, and separate regions that host API services (backed by AWS Relational Database Service (RDS) and a clinical data repository based on the HL7 FHIR standard) and authentication services. The mobile app gets its configuration data about where the appropriate region is located (based on the phone’s locale ID) from the config service in the primary EU environment, and thereafter its data from the appropriate regional environment

Figure 6. Vision Coach regional deployment

- High availability deployment. Application usage levels were difficult to predict in advance, which was part of the reason we deployed on AWS’s Elastic Container Service (ECS), as it enabled us to scale the application easily if required, as well as keep costs under control despite the multi-region set up.

Tasks (Level 5)

Implementation work was documented in sub-tasks attached to the parent ticket in Jira. Generally we took an incremental approach to implementation, starting with a minimum viable product (MVP), and layering up functionality from there. Staying with the phone number verification story, front- and back-end (FE & BE) tasks included:

- Basic OTP input box (FE)

- API call to validate OTP verification completion (FE)

- UI control to navigate to previous screen (FE)

- Additional integration work once real API was available (FE)

- Implement mock API endpoint for front-end developers to work against early on (BE)

- Implement real API endpoint to validate OTP against value stored in the database (BE)

Increments beyond MVP included the following tasks (FE & BE):

- Automatic submission of OTP on entry of last digit in verification code

- Automatic routing to next screen in onboarding on OTP validation

- Resending OTP where delivery fails

Challenges and solutions

We encountered a number of challenges developing and managing requirements using the approach sketched out here. These were the main ones and some of our solutions:

- Latent needs. Users and client stakeholders often don’t know what they want, think they know what they want (but don’t really), want things they assume others will just know... and it’s your job to elicit these requirements then build stuff that satisfies them. The best way to do this is to ship working software to a representative sample of users in a real-world setting, but since iterations with a full cross-functional teams are expensive, where we could we used rapid prototyping techniques to get useful (though admittedly weaker) feedback early on at a lower cost.

- Compliance and user input. All interaction with patients and doctors had to be planned, documented, reviewed and approved by compliance (legal, medical and regulatory), so was neither quick nor easy. Whenever we wanted user feedback, we had to produce a discussion guide complete with PDFs of all screens to be shown for review by the relevant local compliance team. This made user interaction during development less frequent than we would have liked, but not impossible. We dealt with this by creating recyclable templates for discussion guides, and building PDF generation into our automated end-to-end test suites, so that production of the assets needed for review was easier on an ongoing basis. This helped accelerate timelines for getting our software in front of users.

- Enterprise is slow. Everything in enterprise happens slowly. This meant iterative development could be slow, and requirements were often in different states of readiness. A few things helped: (i) an implementation plan sequenced to allow for clarification and validation in areas that needed more time, (ii) working on features that had better developed requirements first; (iii) ensuring we bore no risk for parts of the process we didn’t control.

- Enterprise isn’t agile. Enterprises aren’t usually agile, and healthcare enterprises certainly aren’t. Our project lead, however, was attracted to new ways of working, so we embedded client review and feedback at a global level into the showcases at the end of every sprint (more frequent interaction/decision making was unrealistic). This worked well to elicit additional client requirements throughout the project. The main challenge was going through compliance reviews before launch, which was a local process done on a (near) final asset and not set up to work iteratively, which meant interaction, and must-have requirements, came late in the cycle. This process was unchangeable, so really the only solution available to us was building contingency into the delivery schedule. This contingency turned out to be insufficient, though we were able to trigger a contractual extension that allowed us to minimise financial downside for us, at least.

- Lots and lots (and lots) of stakeholders. Eliciting requirements from lots of stakeholders spread over the globe was impractical for a small team with limited resources. We solved this by creating a core team at a global level whose job it was to represent the requirements of stakeholders across the business and facilitate contact with them, where necessary. We who had scheduled touch points with our team and process. This worked pretty well in many areas, but of course wasn’t perfect, the main area requiring additional work being compliance, which was quite different across localities.

- User stories or use cases? User stories provided us with a concise way of describing a user need, and could be understood by stakeholders. They also have disadvantages, many of which are highlighted by Alistair Cockburn in a great piece on the limitations of user stories vs. use cases, namely lack of (i) context for designers, (ii) completeness for dev teams and (iii) granularity for planning/research. Whilst use cases can fill these gaps, they are also harder to write and more difficult for stakeholders to understand. We decided to combine elements from each - user stories with acceptance criteria formed the core, supplemented with acceptance criteria for alternate goals (like extension points) and UML diagrams (e.g. using PlantUML’s human-readable syntax rather than XML) to provide context for technical design and granularity for timely assessment.

- Scope creep. This happens on all projects. Naturally we built contingency buffers in for this, which provided some leeway for scope increases within budget. On this particular project, a lot of the scope creep came from local compliance teams, particularly in countries with more onerous requirements e.g. the UK and Canada. Since these requirements were often handed to us in the form of solutions — which frequently conflicted with what had been implemented to satisfy patients or doctors — we first spent time identifying the underlying requirements, then worked out how to satisfy them in a way that was consistent with other user requirements. Sometimes this was possible, other times it was not, and compliance won the day.

Summing up

Though much of what you read online about requirements development suggests approaches are polarised between Analysis paralysis and Iteration worship – and most people are aligned to the latter – there are intermediate approaches that can yield real benefits quickly.

For my money, the most material benefits of an intermediate approach like the one described here are improved velocity, cash burn and team morale as a result of improved decision making due to better context. From personal experience, I have watched our team’s velocity improve by ~40% as a result of spending time thinking about and defining requirements properly.

This "objective" measure comes with some caveats - it it is calculated crudely by measuring the difference between average story points completed per sprint for a defined period pre and post introduction of better requirements development, and it fails to control for other confounding variables (e.g. personnel changes).

But directionally it’s interesting, and the fact it was also accompanied by a dramatic improvement in subjective measures - team morale and satisfaction with progress made during sprints - provides some additional evidence.

In summary, the ROI on that initial investment of time and effort is material and the payback period can be as short as a single sprint, so it is definitely worth doing.

What would I do differently next time? Short of coming up with a magic way of making compliance functions totally agile and fully integrated with the development cycle, the top things I would do are:

- Come up with acceptable ways of involving local compliance teams earlier in the development cycle e.g. by involving more of them with prototype review to flush out relevant requirements earlier

- Figure out how to capture non-functional requirements in a more consistent and measurable way, looking at formalisms like Planguage for inspiration

- Use a different toolchain to manage requirements - using a combo of Jira and static sites for docs had a number of problems that I’ll cover in my next post.

What’s next

Part 3 focuses on tools for managing requirements. It includes an analysis and evaluation of tools we’ve used in the past, and that other modern software teams tend to know about and consider when deciding how to manage their requirements.

Bibliography

- A. Cockburn, Writing Effective Use Cases, Addison-Wesley Professional, 2000

- A. Cockburn, Why I Still Use Use Cases, 2008

- D. Gause & G. Weinberg, Exploring Requirements: Quality Before Design, Dorset House Publishing Company, Incorporated, 1989

- D. Leffingwell, Agile Software Requirements, Addison Wesley, 2010

- G. Moore, Crossing the Chasm, 3rd Edition, Harper Business, 2014

- K. Wiegers & J. Beatty, Software Requirements, 3rd Edition, Microsoft Press, 2013

A special thanks to Karl Wiegers for his helpful review comments!