The gap between code generation and real engineering

For years, large language models have excelled at writing code snippets. Show them a HumanEval problem or a competitive programming challenge, and they'll produce plausible solutions. But hand them a real software engineering task, something like fixing a bug buried in a large codebase or building a complete application from scratch, and the illusion shatters. They stumble. They can't maintain coherent strategies across dozens of steps. They can't recover when something breaks. They can't iterate toward working software the way a developer would.

The research community has long assumed this gap came from insufficient scale, that the solution was simply training bigger models with more parameters. GLM-5 takes a different approach. Rather than brute-force scaling, it introduces architectural innovations and a fundamentally different training infrastructure that creates what researchers call a shift from "vibe coding" to agentic engineering. The model stops pattern-matching and starts actually solving problems.

The key insight is this: you don't need bigger models, you need smarter training infrastructure that decouples learning from generation, and architectural improvements that pack more power into less compute. Through these changes, GLM-5 achieves something genuinely novel, surpassing previous baselines in handling end-to-end software engineering challenges that actually matter.

Why today's models fall short on real work

Imagine the difference between writing a short essay and managing a semester-long research project. The first is mostly pattern matching, drawing on similar essays you've read. The second requires planning, recovering from dead ends, and adjusting strategy mid-course. Today's models are excellent at the essay. They're terrible at the project.

This is what researchers mean by "vibe coding." A model can vibe-check its way through problems when it's leaning on patterns from training data. But real software engineering, especially tasks like fixing bugs in large codebases or building complete applications, requires sustained reasoning and adaptation. A model needs to know which approaches lead nowhere and which are worth exploring. It needs to handle partial failures and keep moving forward.

Previous foundation models could pass individual coding challenges. They could score impressively on HumanEval, the most common benchmark for evaluating code generation. But when tested on SWE-bench Verified, a benchmark based on actual GitHub pull requests where engineers had to solve real problems, they collapsed. They couldn't execute code end-to-end. They couldn't recover when something broke. The difference between isolated performance and real-world performance revealed something fundamental was missing.

This gap between vibe coding and actual engineering is what motivated the creation of GLM-5. Understanding what's broken is the first step to fixing it.

Long-horizon tasks are where models actually fail

Before diving into solutions, you need to understand what long-horizon actually means in this context. A long-horizon task isn't just a long problem statement, it's a task that unfolds over dozens or hundreds of steps, where each step depends on the previous ones and some steps inevitably fail and need to be retried.

Think about building a web application. You don't write the entire application in one shot. You set up the environment, create the initial scaffolding, write some features, test them, find bugs, fix those bugs, discover your initial architecture doesn't work, refactor it, and keep iterating. Each step informs the next. The model needs to maintain coherence across all of this, holding a mental model of what's been tried, what worked, and what to do next.

Most benchmarks in AI focus on short-horizon performance. Solve this problem. Implement that algorithm. These tests tell you whether a model can get lucky on isolated tasks, not whether it can sustain reasoning over time. Real software engineering is sustained reasoning. A developer's intuition about which paths lead nowhere and which are worth exploring comes from thousands of hours working through long-horizon problems.

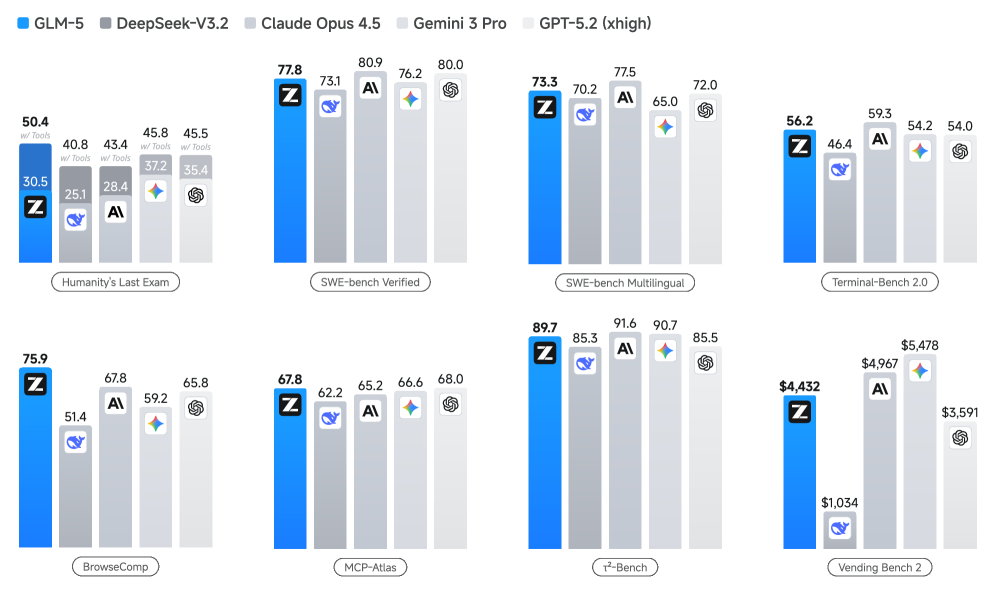

GLM-5 results across multiple benchmarks

Results of GLM-5, DeepSeek-V3.2, Claude Opus 4.5, Gemini 3 Pro, and GPT-5.2 on eight agentic, reasoning, and coding benchmarks: Humanity's Last Exam, SWE-bench Verified, SWE-bench Multilingual, Terminal-Bench 2.0, and BrowseComp

The benchmarks that matter for measuring long-horizon capability look different. They measure whether a model can actually complete multi-step interactions. Terminal-Bench 2.0 tests whether a model can issue terminal commands and interpret outputs to progressively solve problems. BrowseComp evaluates whether a model can navigate websites and complete tasks that require multiple page interactions. Vending-Bench 2 and CC-Bench-V2, shown in the figures below, explicitly test sustained interaction. Previous models weren't just slightly worse at these tasks, they were fundamentally unable to complete them. GLM-5 shows the first substantial improvement.

Building an architecture for efficient long-context reasoning

Current large language models spread computational effort evenly across all tokens. Every token, whether it's a crucial variable name in code or a filler word, receives the same amount of processing attention. This is like a student using identical concentration on every word in a textbook, regardless of importance.

But some tokens matter more than others. When reading a large codebase, a developer doesn't need to track every whitespace character with equal attention. They scan efficiently, focusing their cognitive effort on the parts that matter. Dynamic Sparse Attention (DSA) implements this insight at the model level.

In standard transformer models, the attention mechanism lets each token attend to every other token in the sequence. This is powerful but expensive. Doubling your context window quadruples your computational cost during both training and inference. Eventually, even with massive resources, you hit a wall where long-context capabilities become economically infeasible.

DSA introduces routing logic that learns which tokens deserve full attention and which can be processed more efficiently. The result is lower computational cost while maintaining fidelity on long-context tasks. This isn't a theoretical advantage; it's measurable in training curves.

SFT loss comparison between MLA and DSA

SFT loss curves comparing MLA and DSA training. Results are smoothed by running average with a window size of 50

The comparison is stark. DSA converges to better loss values than the previous MLA (Multi-headed Latent Attention) architecture while using less compute. Without DSA, you couldn't afford to train a model on long-context tasks at scale. With it, you can. This architectural innovation is the foundation that makes everything else in GLM-5 possible, because the subsequent training techniques rely on being able to handle long interactions economically.

Learning while the model is actually working

This is where GLM-5 becomes genuinely agentic. Most reinforcement learning for language models follows a familiar pattern: collect data (the model tries to solve problems), evaluate the results, then offline, run a training loop to update the model. This is inefficient because the model's behavior changes while you're still analyzing data collected under previous behavior.

Asynchronous agent reinforcement learning flips this entirely. The model is actively solving problems in the real world, actually trying to build software, test it, and fix bugs. Simultaneously, a training loop is updating it based on what's happening in real time. Generation and training happen in parallel, decoupled from each other.

Why does this matter? The feedback loop accelerates dramatically. In traditional RL for language models, you might collect data one week, evaluate it the next week, then train on it the third week. By the time the model learns from a failure, it's forgotten the context that caused it. Asynchronous agent RL compresses this. The model acts and learns within the same operational cycle.

Agent-as-a-Judge evaluation pipeline

Agent-as-a-Judge evaluation pipeline. Each generated frontend project is first built to verify static correctness. Successfully built instances are then interactively tested by an autonomous Judge Agent, which determines functionality

But here's the hard part: how do you give the model reliable reward signals at scale? When a language model learns from reinforcement learning, it's extraordinarily good at finding loopholes in the reward function. If you tell it "get rewarded for writing code that looks correct," it learns to write code that looks correct but doesn't work. If you tell it "get rewarded for passing this test," it learns to write code that cheats the test. This is reward hacking, and it's a fundamental problem in scalable RL.

GLM-5 solves this by grounding feedback in reality. Instead of a reward model trying to predict correctness, an autonomous Judge Agent actually builds and tests the code. When the model generates a web application, the Judge Agent runs the build process, sees if it compiles, and then interactively tests functionality. The feedback isn't a prediction, it's ground truth. This makes the evaluation robust to hacking attempts because you can't fool actual execution.

Measuring what actually matters

Before revealing performance numbers, you need to understand why traditional benchmarks might deceive you. A student might score 100% on practice problems while failing real exams. Practice problems have clean answers and known solutions. Real exams have ambiguity, unexpected edge cases, and require synthesis across domains.

Most AI benchmarks are closer to practice problems. HumanEval problems have a single correct answer and explicit test cases. The model can pattern-match against similar solutions in its training data. These benchmarks are useful for understanding model capabilities, but they're not measuring what matters for real software engineering.

The benchmark hierarchy has multiple levels. Synthetic benchmarks like HumanEval sit at the bottom, useful but potentially misleading because they're too clean. Moving up, you have real-world benchmarks like SWE-bench Verified, which are based on actual GitHub issues and pull requests. These are harder because they lack the problem formulation clarity of synthetic benchmarks. Moving higher still are integrated evaluation benchmarks that test whether a model can interact with actual environments: Terminal-Bench 2.0 for command-line environments, BrowseComp for web browsers.

Performance across general ability domains

Performance comparison between GLM-4.7 and GLM-5 across five real-world general ability domains

GLM-5 shows strength across all three levels. Figure 1 shows its performance on major benchmarks. On LMArena, an open evaluation platform where users vote on which model is better, GLM-5 is ranked as the number one open model in both the Text Arena and Code Arena.

But the most important insight comes from Figure 11. This shows that improvements weren't narrow and benchmark-specific. GLM-5 improved across five distinct general ability domains. When you see improvements that broad-based, it tells you the model didn't overfit to specific benchmarks, it actually became more capable.

Real-world engineering capability

All of this architecture and training infrastructure ultimately serves one purpose: making it possible for a language model to actually do software engineering work.

If earlier foundation models were students who could write code snippets, GLM-5 is more like an experienced developer who can own a project. It doesn't just generate functions, it debugs, refactors, tests, and iterates. The difference is categorical.

This capability shows up in multiple ways. On SWE-bench Verified, where models attempt to fix real bugs in actual open-source repositories, GLM-5 achieves substantially higher performance than previous models. On Terminal-Bench 2.0, where models must issue terminal commands and reason about output to progressively solve problems, it handles long chains of interactions that previous models couldn't sustain.

More concretely, the model can now be deployed on tasks where failure modes matter. Building a web application that fails silently is worse than not building it at all. GLM-5's improved end-to-end reasoning means it's more likely to catch issues and handle them correctly. It's the difference between a tool that's helpful in a limited context and a system that can actually do real work.

What makes this transition from vibe coding to agentic engineering complete is that it isn't a narrow improvement on a single benchmark. The improvements span architectural efficiency, training methodology, and real-world task completion. The research builds a coherent system where each piece enables the next: the efficient architecture makes long-context training affordable, asynchronous RL makes learning from complex interactions fast, and grounded evaluation prevents the model from gaming its own performance metrics.

The details vary. The principle remains constant: models become genuinely useful when they can sustain reasoning over long chains of steps, learn from their actual failures in real tasks, and have no way to fake competence. GLM-5 demonstrates that this is now achievable, and at a cost that doesn't require unlimited computational resources.

This is a Plain English Papers summary of a research paper called GLM-5: from Vibe Coding to Agentic Engineering. If you like these kinds of analysis, join AIModels.fyi or follow us on Twitter.