What web browsers do when a user requests a page is quite a remarkable journey. My goodness, the process behind the curtains reflects a diligent effort by the folks who build browsers. So far, I’ve found it very interesting to navigate through the steps taken to draw pixels on the screen. I’ll admit it—this is a surprisingly deep and fascinating area. As developers, we tend to focus heavily on performance, especially when building at scale.

If we want to have a strong grasp of browser rendering performance metrics and how to improve bottlenecks, I feel we’d be better off continuing down this route, equipping ourselves with the right combination of knowledge, experience, and tooling. Otherwise, long load times for fully interactive pages—or slow responses to user interactions—can easily ruin a good user experience. After all, the only thing that truly matters in software is the user experience.

So today, I want to lay out some of the insights I’ve picked up from writing code, reading articles, and watching various conference talks about the absolutely critical, need-to-know aspects of page rendering on the web. Let’s put in the work.

It all starts when a request is entered into the address bar. That submission initiates a DNS lookup if the website is being requested for the first time, though caching may help speed things up. The DNS lookup returns an IP address, which points to the server where the requested file is stored. Once the browser has the IP, it establishes a connection so the two can communicate effectively—this is known as the TCP handshake. But efficiency isn’t the only goal. The connection also needs to be secure, ensuring no third party can read the data being exchanged. To achieve this, another handshake takes place, known as TLS negotiation.

All the back-and-forth messages are done via the HTTP protocol. Once the connection part is done, the browser then sends a GET request for the HTML file, and the server starts to send the raw data in batches, as the server can send the response in chunks, especially for larger responses, since that’s the core part of web infrastructure.

I like the analogy that I found in the MDN docs. It states like this: If we imagine that the internet is a road. At one end of the road is the client, which is like our house. On the other end of the road is the server, which is like a shop we want to buy something from.

Then the internet connection is basically like the street between our house and the shop. DNS is like looking up the address of the shop before we visit it. TCP is like a car or a bike (or however else we might travel along the road), and HTTP is like the language we use to order our goods.

Once the handshake and connection are done, the browser starts to assemble them into something meaningful that the user wants to see.

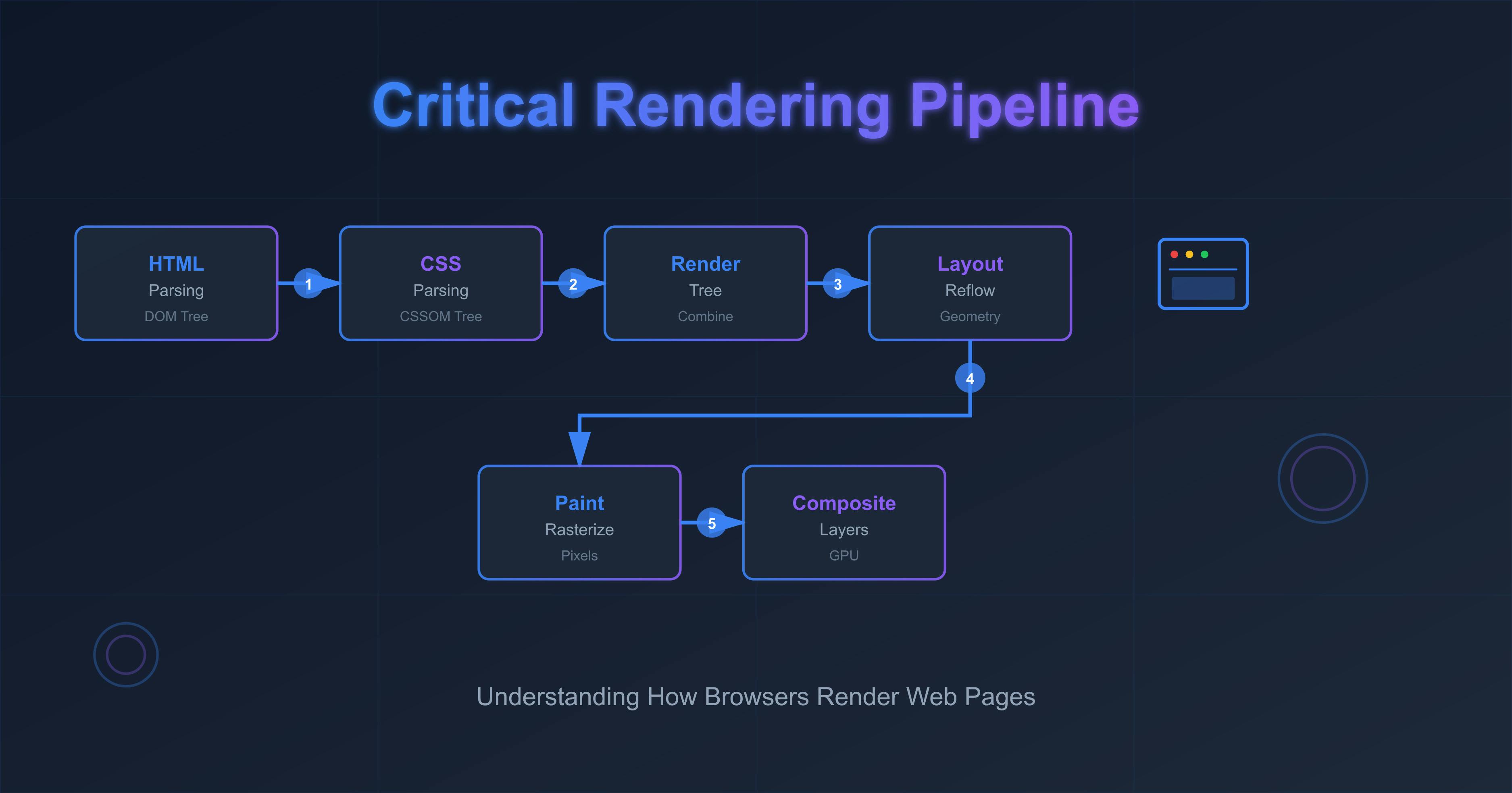

To achieve that, it has a couple of pipelines to go through to convert the bytes to visual pixels on the screen.

As soon as the browser gets the first chunk of raw bytes, it needs to build a structure it can work with. And for that, it converts the raw bytes to tokens, which are like vocabularies of a language. From tokens, it generates nodes, which contain all the information necessary about a certain HTML element, and all the nodes are modeled into a tree data structure, which functions as a relationship model between things. This internal representation of the HTML file is known as the DOM tree. It can be manipulated by various DOM methods and properties in JavaScript.

While parsing the HTML, the parser may find stylesheets, which can’t modify the DOM, so the building of the DOM tree process continues along with downloading and parsing CSS to build the CSSOM tree. Parsing the CSS involves resolving conflicting CSS declarations, as CSS can come from different sources, i.e., user agent, author declarations, etc.

The browser needs to build both trees independently because the next step, which is render tree creation, can't be done unless the DOM and CSSOM are ready. Had it done only the DOM tree, then we’d have experienced an un-styled page for a moment, and after some time, proper rearrangement would get placed because of styling, which would feel broken.

Speaking of external resources such as images, stylesheets, scripts, and fonts, optimization happens alongside parsing HTML through the preload scanner, which starts downloading the CSS, font, and script files that are high priority. The browser has internal rules of which files get prioritized, but we can also control this behavior by <link rel="preload"> tag.

<link rel="preload" href="very_important.js" as="script">

This optimization was invented because, back in the old days, when a script tag was found, that would pause the HTML parsing because JS can manipulate the DOM. Instead, that script was first fetched, parsed, and executed before starting to resume the parsing. This way would delay the discovery of other files and bring waterfalls. Like this:

To prevent this waterfall, resources are downloaded in parallel so that when the HTML parser finds resources, those might already be in flight or have been downloaded.

JS can also manipulate styles. So before JS execution, all the CSS files have to be downloaded and parsed and the CSSOM must be ready.

For instance, if we place the script tag in the head and before that script we put a link tag with a stylesheet, then when the HTML parser encounters the script, it stops parsing, but at the same time, JS also can’t be executed if CSSOM is not ready. As we can see, the consequences of delaying building the CSSOM and code structure can drag down both the JS and HTML parsing. That’s why the preload scanner’s main goal is to download the CSS files as quickly as possible so that CSSOM can be available in record time.

CSS needs to be downloaded and parsed completely before JS can be parsed and executed. Even though browsers have preload scanners, we should place the script tag at the very end and the styles at the top for that reason.

But nowadays we have better alternatives. If we place the script in the head and don’t want to pause the HTML parsing, we can mark the defer attribute on the script tag, and that will fetch the script in the background and start execution after the HTML has been fully parsed.

Coming back to the pipelines, since the DOM and CSSOM are ready, the browser starts to traverse the DOM tree, and for each node, it makes sure it has all the information for that element, plus it calculates the computed values from the CSSOM tree, figures out which styles apply to which elements, and forms a render tree. This tree excludes invisible elements like the head tag and its descendants, and CSS declarations with display: none.

Now that the browser has the render tree in place nicely, it starts to traverse the render tree to calculate what dimensions each node should have and exactly where on the screen the node will sit based on a couple of factors. Some of these are: device viewport size, CSS box model, CSS layout modes (flex layout mode, grid layout, positioned layout, flow layout etc.). This process is referred to as layout calculation; if this is running for the first time, but on subsequent reruns, it’s called reflow.

So far, the browser has the render tree consisting of nodes and has done all the calculations of where they need to be painted. Coming to the actual drawing work, this is where the browser figures out which colors to assign to every visual element in the render tree (“rasterization”) and fills it in.

To ensure repainting can be done faster, drawing the page split up into distinct layers, sometimes depending on the styles we are using, so that it can re-paint only the part that needs to be changed, and after repainting, the browser then offloads layers to the compositing phase so that it can merge all the layers together into one final image. Similar to design mockups in Figma and others. With this method, the painting process can reuse the work it has done in the previous paint and only change what hadn’t been done previously.

Styles calculation, layout, and paint phases happen in the main thread in the CPU. The Compositing phase happens on a different thread, which is inside the GPU, where the expensive calculations are done much faster than on the CPU.

When the browser breaks up the paint process into layers, after the painting process, those layers consist of painted pixels (A.K.A. textures or flat images). Earlier, I mentioned that, depending on the styles, browsers create separate layers, and those are transform, opacity, will-change, filters, and a couple more. And if we animate these properties, they don’t trigger layout or paint phases. Instead, they can be animated with compositing alone and a little bit of style re-calculation. The layout and paint phases won't rerun in this case, which reduces the work greatly. Otherwise, we would have done those expensive measurements many times a second. Leveraging this leads to a smoother motion.

Make use of any of these properties to treat our element like a single image on a separate layer and then does the texture-based transformation, which is essentially to move, scale, rotate or fade the already painted pixels and then merge that layer with other layers to form a single bitmap, which can be shown on the UI. Since these happen on the GPU, it makes the animation very slick and performant. This is known as hardware acceleration.

Sometimes it brings one problem though: when the CPU hands it to the GPU to animate the transform property, there's a slight glitch that can appear in text when animating because of a slight difference in the method they use to render things. To remove that, we can use the following CSS:

.btn { will-change: transform; }

This now will be managed by the GPU all the time, with no handing off. You can try this exercise by yourself. Try creating a button, and then on hover translate it a little bit up or down. You will notice that the text shifts slightly or the characters’ thickness grows or shrinks a bit.

Compositing can also be very useful with smooth scrolling. For example, in the early days of the web, when user scrolled, the entire page had to be re-painted again which felt laggy and kind of redundant.

So to skip the paint process, the browser now transforms the page's content up or down when the user scrolls. So by sliding up and down, it speeds up the frame rate in lightning quick time, as it doesn’t have to do many calculations because that has already been done by the paint process. It just stacks up the layers in correct orders, transform them up or down and combine them correctly into a single image.

Important to remember here is this layering work is done by the GPU instead of the CPU, which improves performance, but it does take up memory, so that’s the tradeoff we need to be aware of.

Which steps will re-run in the pixel pipeline depends on CSS properties. If an element width is changed from 200px to 300px on hover, then that will trigger the layout phase since an item growing might mean that its siblings move to fill the space. And then the re-paint and compositing. That’s the reason it’s best to avoid changing layout properties like width, height, margin etc., especially when animating, because that’s how we can skip a bunch of operations. Libraries like framer motion achieve animating layout properties with various techniques like FLIP.

But elements that have been taken out of the normal flow (i.e., absolute), changing width or height don’t affect the other elements. So cases like this, layout calculation, repaint usually happen much faster.

A quick plug: all the pipeline work that I mentioned (render tree construction, layout, painting, and compositing) is constrained with a tight time of ~16ms to make the UI motion feel fluid and believable. And the steps are blocking and sequential, as we’ve witnessed, done by one thread, which is the main thread. However main thread must also perform other tasks, such as responding to user input and executing JavaScript to keep the UI responsive also. And it is considered a bad and sluggish experience if a response to the user interactions and rendering steps both take greater than ~50ms.

To maintain optimal performance, it is also important to make sure JS execution doesn’t take that long.

Like I said earlier, this stuff is really deep. There are obviously many more nuances and intricacies that you can get into at each step and I'll attach some helpful resources for you to dig even deeper. Not sure if I did a decent job of explaining things. Let me know how that turns out for you. I find it quite hard to keep this all straight in my head. But understanding this helps developers to build a pleasurable experience for the end-users.

Hopefully this write-up helped to add some light to your understanding, and you are eager to learn more about it. Thank you so much for the ride.

Resources:

- https://medium.com/@addyosmani/how-modern-browsers-work-7e1cc7337fff

- https://hacks.mozilla.org/2017/09/building-the-dom-faster-speculative-parsing-async-defer-and-preload/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

P.S. If you wish to see how many layers a webpage has then the browser dev-tool has a "layer tab" in which we can visualize them.