Every programming language starts with a grand vision.

Or at least, that’s what I told myself.

Well mine started with Redis.

More specifically, it started with a message that sounded so harmless I didn’t even bother writing notes:

We need to clean Redis programmatically.

No compiler theory.

No syntax design.

No intention of creating anything remotely reusable.

Just a cache cleanup.

At the time, Redis was being used as a high-performance cache for business-critical data. Over time it became mission critical in a high volume data environment and consequently as a result - it had accumulated stale, obsolete, and partially invalid records — the kind that don’t break the system immediately, but quietly rot until they do. At some point our team identified more than 80 million records that could be safely deleted from Redis. And so a tech debt Jira ticket was born.

The task was simple:

-

identify which records should be removed

-

mark others as logically deleted using a TOMBSTONE flag

-

run the cleaning job every night

-

do it safely, without breaking downstream consumers

What I didn’t realize was that this was the first step toward accidentally building a programming language.

1. The Innocent Requirement

Redis was being used as a hot cache for business-domain entities I’ll call LedgerRecords.

A LedgerRecord wasn’t a simple cache entry. It represented real business state and contained nested data and references to other entities. A simplified version looked something like this:

{

"id": "LR-983712",

"status": "SETTLED",

"amount": 1250.50,

"currency": "USD",

"createdAt": "2023-09-14T12:32:11Z",

"account": {

"id": "ACC-441",

"country": "US",

"riskLevel": "LOW"

},

"childrenIds": ["LR-983712-1", "LR-983712-2"]

"tombstone": false

}

In other words, Redis was caching entire domain objects, not just computed values.

Keep an eye out for “childrenIds”they will be important later on in the story.

Over time, the cache accumulated records that were no longer valid from a business perspective. Some could be safely deleted. Others still needed to exist because downstream systems referenced them — but only in a logically deleted form, marked by setting tombstone = true.

2. Turning Business Rules into Code

From the start, I knew hard-coding business rules would not age well.

The rules were owned by the business, changed frequently, and had a habit of growing new clauses every time someone said “just one more condition”. I didn’t want a cleanup job held together by dozens of nested if statements.

So instead of writing rigid logic, I made the rules configurable — but intentionally limited. Just simple comparisons and an if / else decision.

{

"if": {

"field": "createdAt",

"operator": "<=",

"value": "now-90d"

},

"then": "TOMBSTONE"

}

Nothing fancy. At this point over-engineering was a concern of mine and thus the goal was clarity, not power.

The first version of the evaluator was deliberately boring:

Action evaluate(Rule rule, LedgerRecord record) {

Object fieldValue = resolveField(rule.field(), record);

boolean result = switch (rule.operator()) {

case "==" -> fieldValue.toString().equals(rule.value());

case "<=" -> compareAsInstant(fieldValue, rule.value()) <= 0;

case ">=" -> compareAsInstant(fieldValue, rule.value()) >= 0;

};

return result ? rule.thenAction() : rule.elseAction();

}

At this stage, the system could handle basic equality checks and timestamp comparisons — and nothing more.

Which, at the time, felt like the right level of restraint.

It turned out to be just enough structure to invite the next request.

3. “Just One More Condition”

The PO loved the idea of config-driven rules.

Not because it was “architecturally elegant” — but because it was readable. They could look at a JSON file and say: “Yes, this matches what we want.”

No redeploy just to tweak a threshold. No code review for changing a rule from 60 to 90 days.

And then came the message that always arrives right after version one “works”:

Can we support AND / OR as well?

The first example was perfectly reasonable:

- delete if status == INACTIVE OR createdAt is older than 90 days

In JSON, that sounded like:

{

"if": {

"or": [

{ "field": "status", "operator": "==", "value": "INACTIVE" },

{ "field": "createdAt", "operator": "<=", "value": "now-90d" }

]

},

"then": "DELETE",

"else": "KEEP"

}

Still harmless… right?

But this request changed the shape of the system. Because now “a condition” was no longer a single comparison. A condition could be:

- a simple comparison,

- a logical OR of multiple conditions, or

- a logical AND of multiple conditions.

Which meant the evaluator had to become recursive.

I replaced the “single comparison” model with a small expression tree. Still minimal, still intentionally constrained:

enum Operator {

EQ, LT, GT

}

enum Action {

DELETE, TOMBSTONE, KEEP

}

record Rule(String field, Operator operator, String value, Action thenAction, Action elseAction) {}

sealed interface Expr permits ComparisonExpr, AndExpr, OrExpr {}

record ComparisonExpr(String field, Operator operator, String value) implements Expr {}

record AndExpr(List<Expr> items) implements Expr {}

record OrExpr(List<Expr> items) implements Expr {}

And the evaluation turned into:

boolean eval(Expr expr, LedgerRecord record) {

return switch (expr) {

case ComparisonExpr c -> evalComparison(c, record);

case AndExpr a -> a.items().stream().allMatch(e -> eval(e, record));

case OrExpr o -> o.items().stream().anyMatch(e -> eval(e, record));

};

}

boolean evalComparison(ComparisonExpr c, LedgerRecord record) {

Object fieldValue = resolveField(c.field(), record);

return switch (c.operator()) {

case EQ -> fieldValue.toString().equals(c.value());

case LT -> compareAsInstant(fieldValue, c.value()) < 0;

case GT -> compareAsInstant(fieldValue, c.value()) > 0;

};

}

This still felt manageable. In fact, it felt nice:

-

AND naturally short-circuited with allMatch

-

OR short-circuited with anyMatch

-

comparisons stayed unchanged

And now that we had AND / OR, the next question became inevitable:

Can we nest them?

Because the moment you support OR, someone wants:

-

(A OR B) AND (C OR D)

And once you support nesting…

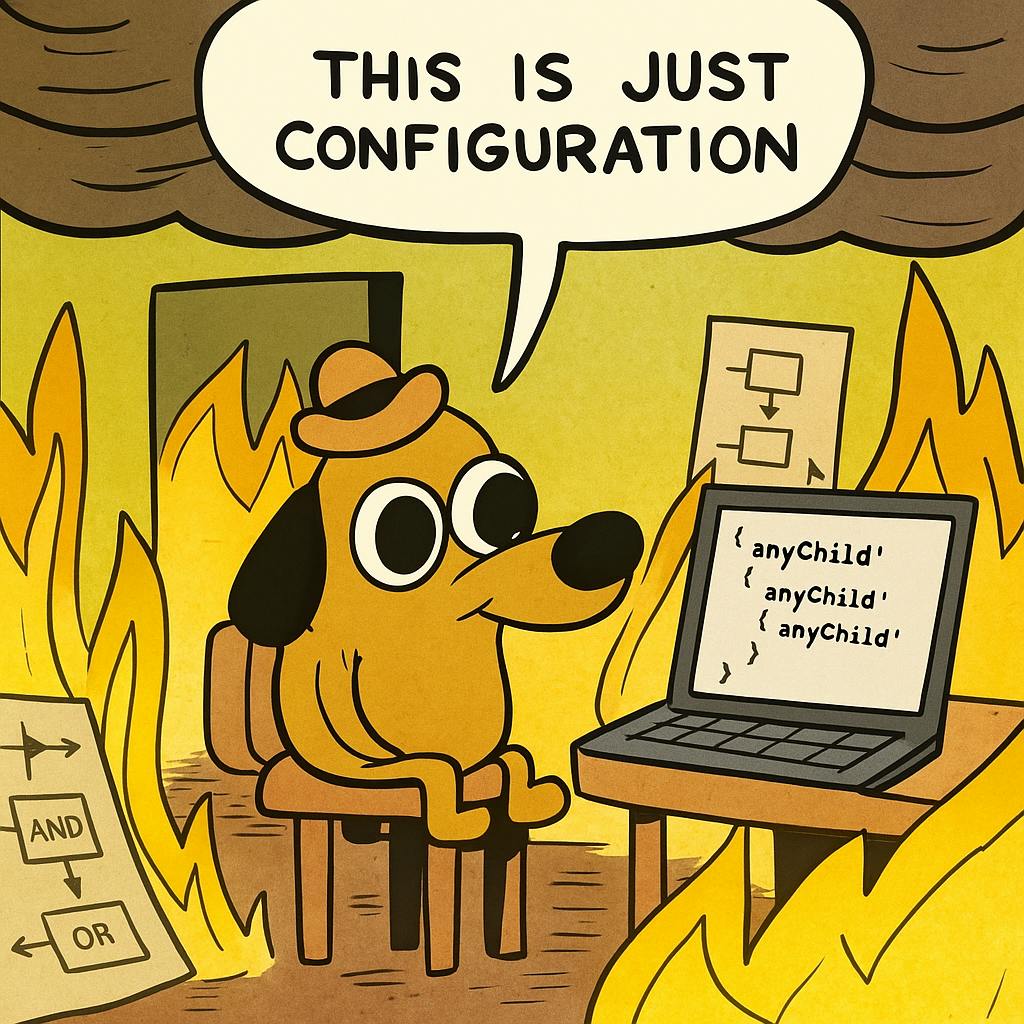

…it stops being “config”.

Well it starts being a pseudo-language.

4. “Can we check inside children?”

The PO, exited, wanted for the next iteration to add recursive children checking. Remember the “childrenIds” field? Some LedgerRecords acted as parents to other records, and special business rules applied to them. Naturally we had to give special consideration to these records during cache-cleaning as well.

These records had some complicated scenarios to support. To give you an example:

Delete a record if it has

- status == inactive

OR

- it has a childA that has

- createdAt older than 30 days

- AND

- childA has a subChild that in turn

- has status == inactive

In other words we had scenarios that had complex checks 3 or even more “hops” deep. Expressed in json it looked like

{

"if": {

"or": [

{

"field": "status",

"operator": "EQ",

"value": "INACTIVE"

},

{

"anyChild": {

"where": {

"and": [

{

"field": "createdAt",

"operator": "GT",

"value": "now-3d"

},

{

"anyChild": {

"where": {

"field": "status",

"operator": "EQ",

"value": "INACTIVE"

}

}

}

]

}

}

}

]

},

"then": "DELETE"

}

At this point, this wasn’t just evaluating conditions anymore.

I was:

- walking a graph

- managing execution depth

- switching evaluation context

- and interpreting a declarative rule over dynamic data

I still hadn’t intended to build a programming language.

But the system was starting to behave like one.

5. I Accidentally Made My PO a Programmer

By now, I had effectively turned my PO into a programmer. They were no longer just describing requirements — they were authoring executable logic. Logic that could traverse linked records, interpret timestamps, and delete data from Redis.

And I know one thing for a fact:

Programmers mess up.

Not because they’re careless — but because systems get complex, rules interact in unexpected ways, and production data always finds the one edge case you didn’t think about.

Once the rule configuration reached this level of power, mistakes stopped being theoretical. A single misconfigured condition could:

- wipe out large portions of the cache

- tombstone records that should have stayed alive

- cascade through linked records in ways that weren’t obvious from the JSON

At that point, “just fix the config and redeploy” was no longer a viable recovery strategy.

The safety net: cache restore

The solution was to make rule execution reversible. Before performing any destructive operation on Redis, the system began to serialize every step of execution to PostgreSQL.

For each evaluated record, I stored:

- the record ID

- the action taken (DELETE, TOMBSTONE)

- the original cached value

- the rule that triggered the action

- a timestamp and execution batch ID

Conceptually, each cleanup run became a transaction log.

Run #1842

├─ LR-983712 → DELETE

├─ LR-983712-1 → TOMBSTONE

└─ LR-983712-2 → DELETE

Redis was still fast and ephemeral but PostgreSQL became the system of record for “what did we change, and why?” If a rule turned out to be wrong, recovery was no longer a panic operation.

It was:

- identify the execution batch

- replay the serialized records

- restore Redis to its previous state

At this point, the cleanup job had quietly gained:persistence, execution history, rollback capability

Congratulations, You’ve Built a simple Rule Engine

I never sat down to design one. There was no RFC, no grand abstraction plan, no moment where I said “let’s build a language.” Each step felt reasonable in isolation — almost obvious. But taken together, the system had crossed a line.

The JSON wasn’t configuration anymore it was a rudimental executable logic. The PO wasn’t just defining requirements. They were writing programs.

The most ironic part is that the system worked.

It was readable.

It was flexible.

It was safe enough to run in production.

And if I were starting again, I’d probably build it the same way - even in spite my fears of shipping over-engineered solution.

Just with the honesty to call it what it really was.

Because sometimes, all you wanted to do

was clean a cache.

And instead, you built a programming language…… accidentally.