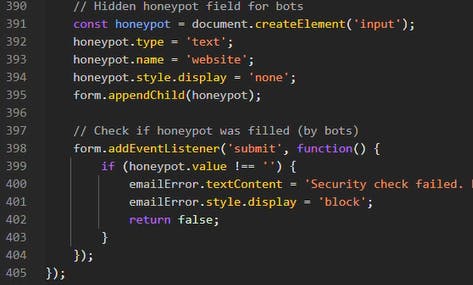

I was analyzing a phishing kit last week when I noticed something in the HTML that shouldn't have been there: a hidden form field with no visible counterpart. Other parts of the code tracked mouse movements, keyboard presses, and clicks to verify human behavior. But buried at the bottom was a hidden input field programmatically added to the form, invisible to users, with the field name "website":

// Hidden honeypot field for bots

const honeypot = document.createElement('input');

honeypot.type = 'text';

honeypot.name = 'website';

honeypot.style.display = 'none';

form.appendChild(honeypot);

// Check if honeypot was filled (by bots)

form.addEventListener('submit', function() {

if (honeypot.value !== '') {

emailError.textContent = 'Security check failed.';

emailError.style.display = 'block';

return false;

}

}

It wasn't part of the UI. The victim would never see it. So, why was it there? Because it wasn't designed to catch victims. It was designed to catch us.

The Invisible Tripwire

As a Cyber Threat Hunter, I analyze dozens of phishing sites per month. Most are either sloppy cut-and-paste jobs or subscription Phishing-as-a-Service kits. But this campaign was a little different. The landing page looked boring enough: a clean, corporate-styled prompt asking the user to "Verify your email address" before proceeding:

As expected, the contents of this field were sent on to the Adversary-in-the-Middle kit, in order to pre-file the email field on the credential request. But when I inspected the DOM, I found a discrepancy between what was rendered and what existed in the code.

Okay, this honeypot field technique isn’t actually new, and in fact, it has a legitimate pedigree. Web developers have used honeypot fields since the early 2000s to protect contact forms and registration pages. The logic is elegant: humans can't see the hidden field, so they leave it empty. Spam bots parse the HTML, see an input called “website”, and dutifully fill it with a URL. Any submission with data in the honeypot gets silently discarded.

It's a brilliant, passive defense. No CAPTCHA friction or user annoyance, just a quiet trap to catch automated abuse. And we see here how phishing operators have copied it, line for line, to catch us.

Here's how it works in their context: Rudimentary security scanners parse raw HTML. When they encounter an input field, their programming compels them to fill it to test for vulnerabilities or trigger a submit action:

- Hidden field empty? Likely human, proceed to AitM proxy kit

- Hidden field has data? Likely bot, display an error message

The Engine Under the Hood: Traffic Cloaking

The honeypot is just one of the entry-level filters. Behind it sits a massive backend industry called Traffic Cloaking. Originally developed to both stop as well as perpetrate ad fraud, now weaponized for phishing. The sophisticated services cost $1000 per month and fingerprint every visitor in milliseconds. That's not script kiddie money; that's infrastructure investment. They're checking:

Behavioral biometrics: Mouse activity, typing rhythm. Humans are messy; bots are linear and instant.

Device fingerprinting: Does navigator.webdriver return true? Does the WebGL renderer identify as "Google SwiftShader" (headless Chrome) instead of actual hardware?

IP reputation: Residential ISP or a security vendor's datacenter?

Poisoning the Well

Here's where it gets devious. When phishing kits detect bots, scanners, and researchers, they don't just block you. They serve a "Safe Page":

Why? To poison threat intelligence feeds.

When a security vendor's crawler lands on that blog, it categorizes the domain as, for example, “Retail” or "Technology/Benign." That classification propagates to firewalls, URL filters, and blocklists, so the domain gets whitelisted. By the time a real victim clicks the link and sees the actual phishing page, the security tools have already stamped it safe.

I've watched domains stay active for weeks or even months using this technique. Without cloaking, most phishing sites get burned promptly.

The Mirror World: Defense Becomes Offense

It always makes me grin when I see that attackers often aren't inventing new techniques, but they're just copying ours.

Legitimate sites use honeypots to keep spam out of their databases, while phishing sites use honeypots to keep scanners out of their infrastructure. Same code, flipped context.

This pattern repeats everywhere:

CAPTCHA, originally designed to defend websites, now appears on at least 90% of phishing sites I analyze. Dual purpose:

Technical: Stops automated crawlers from reaching the phishing content.

Psychological: Builds trust. When victims see a Cloudflare Turnstile or Google reCAPTCHA, they think, "This site has security checks. It must be legitimate."

What's Behind the Curtain

Why work so hard to hide? Because what's protected is valuable: real-time Adversary-in-the-Middle attacks that steal session cookies, not passwords. The kit acts as a live proxy, relaying credentials and 2FA codes to the actual service. When the real site issues a session cookie, the attacker snaps it up. No password needed, no 2FA bypass required. Just grab the token from the cookie, and you're in. Search the inbox for monetizable content, like an invoice to replicate, and then burn it by sending out the next wave of phishing emails. That's worth protecting with counter-intelligence.

How to Fight Back

1. Scan Like a Victim, Not a Server

Cloaking systems blacklist datacenter IPs instantly. In our hunt program, we route analysis traffic through residential and mobile proxies and mimic real hardware/software fingerprints, so we see what targets see. Be aware, though, that sometimes that means the page gets blocked by an ISP security appliance or DNS filtering.

2. Hunt for Negative Space

The honeypot I found was invisible to the eye but obvious as soon as I looked at the code (although, to be fair, this is because this landing page didn’t use any obfuscation). If feasible, update your detection rules to flag hidden form inputs on login pages.

3. Stop Teaching Users That CAPTCHAs Mean Safety

We spent years training users that a padlock icon and a CAPTCHA are good signs, and attackers know this. By now, attackers use CAPTCHA and SSL more than legitimate sites do.

Update your security awareness programs: A CAPTCHA on an unexpected link is not a safety feature. At best, it's a gate designed to keep automated defenses out, and at worst it’s a ClickFix-style attack. If you have to solve a puzzle just to view a "shared internal document," you're walking into a trap.

The Arms Race Continues

Front-end honeypots on phishing sites are just one facet of a broader shift I’ve watched play out over the last few years: attackers treating their campaigns like legitimate SaaS products: optimizing uptime, managing bot traffic, A/B testing landing pages.

We're up against engineering teams with product roadmaps and customer support channels. The fix isn’t another poster about “hover over the link” or a longer PowerPoint about misspellings. It’s a mindset shift in which we stop treating phishing as a side quest. Attackers have already stolen our honeypots, our CAPTCHA, and our playbooks. The only real question now is whether we’re willing to steal something back from them: their discipline. If we can teach our defense teams to apply the science and art of analysis as effectively as attackers do, then the next time hidden code shows up in a phishing kit, it won’t be their tripwire. It’ll be ours.