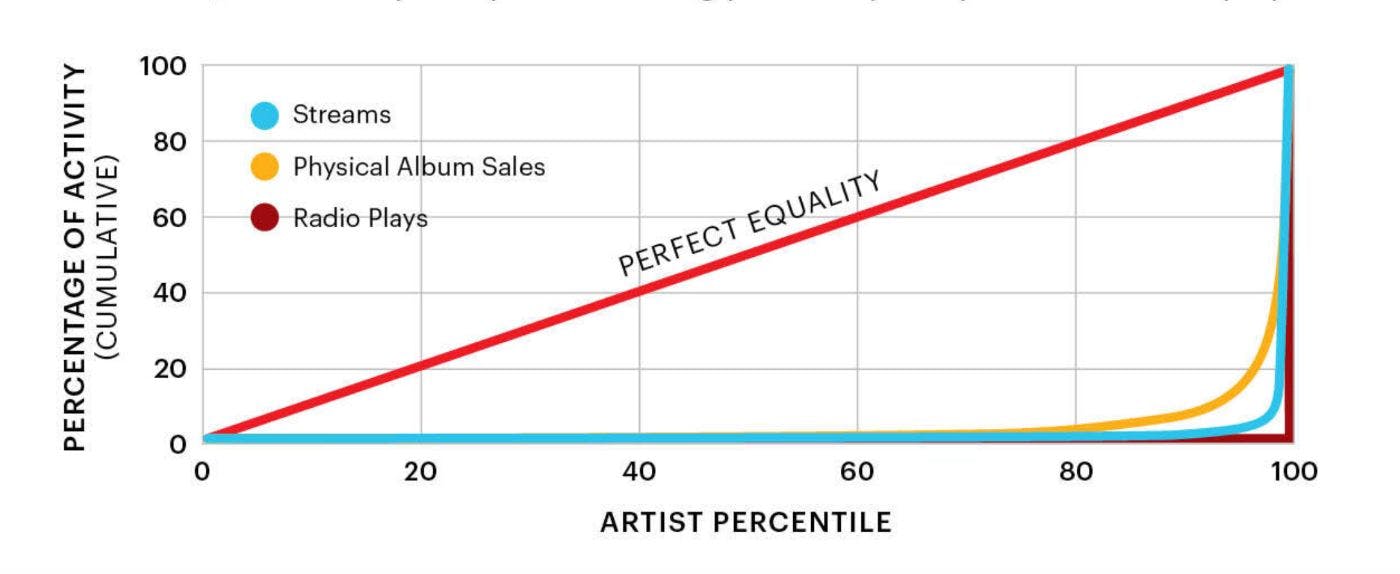

- Empirics: Participation is long-tailed. The old 90/10 baseline is collapsing toward 99/1.

- Mechanics: Cumulative advantage and social influence create self-reinforcing feedback loops and a stable equilibrium.

- Playbook: Map your power user curve, empower keystone contributors, and build growth loops and fair governance to optimize the head’s performance while thickening the tail.

The online worlds we spend our time in are shaped by a fraction of their inhabitants. 99.8% of Wikipedia’s users are lurkers, with just 0.2% of the site’s visitors ever having contributed an edit.

This trend holds true across all online media: artistic or social. 90% of music streams go to just

All these cases reflect a power-law or “heavy head” distribution of participation. A minuscule fraction of creators reaps outsized influence and audience. The long tail of casual contributors or niche creators, while large in number, accounts for only a small slice of the pie.

The Theory: Heavy Heads and Long Tails

While it may seem like we’re adrift in a brave new world of technological incoherence, none of this is exactly new. What we’re witnessing are old dynamics at internet scale. The 20th century music industry was already hit-driven, and streaming intensified that concentration.

In other words, once a signal gains momentum within a network of recursive feedback, it reinforces its own dominance until the system settles into a stable, heavy-headed equilibrium. Those who make it to the top consolidate their position.

That shouldn’t necessarily be seen as distortion, but rather the default of digital systems. On the positive side, unlike fixed-return industries,

And early advantages compound. A small lead (in users, data, or brand) becomes entrenched. Subsequent entrants find themselves fighting uphill against built-in inertia.

Finally, the explicitly social nature of modern feeds (TikTok, YouTube, Spotify, etc.) make popularity highly visible: view/listen counts, likes, trending lists, follow metrics.This visibility inflates variance. Apparent “merit” is magnified by algorithmic feedback: small view gaps get boosted, then compounded. This is why some creators break through while near-peers don’t: randomness + visibility + feedback.

So, that’s the theory. But what is there to do in practice? Are these all uncontrollable stochastic processes we have no hope of influencing? Is our only option to sit back and enjoy the ever-accelerating ride into a world of hyper-stratification?

Not quite.

Three concepts help community managers turn skews into strength.

The Practice: Smiles, Keystones, and Loops

Why do these skewed dynamics matter for creators and community builders? Because understanding and harnessing the power of the “vital few” is the key to growing a successful community.

Rather than viewing extreme inequality as purely a problem, savvy product teams should treat it as a reality to design around.

The Power User Curve

Instead of looking only at average engagement, it’s valuable to plot the distribution of user engagement – a histogram of how many days a user is active or how much content they create in a given period. This curve often has a “smile” shape or L-shape, revealing a small segment of extremely engaged users on the far right.

These are your power users. Tracking the power user curve over time helps determine whether your highly engaged cohort is growing and if more users are shifting rightward into higher activity levels.

It’s a diagnostic tool: a strong uptick on the right of daily active users often correlates with functioning network effects and effective retention, whereas a flat or left-heavy curve could signal that users aren’t finding enough value to stick around daily.

Keystone Contributors

In architecture, a keystone locks the arch. In communities, keystone users lock the culture: moderators, prolific posters, core maintainers.

Perhaps counterintuitively, the most important support in such structures is not at the bottom, but the top.

On a forum, this might be the handful of moderators and prolific posters who spark most discussions. On an open-source project, it’s the core maintainers and frequent committers.

If the top 1% drives the content, you cannot afford to lose them. Design tools and incentives for them: advanced creation workflows, revenue share, moderation privileges, public recognition (badges/leaderboards), and in Web3, governance or token stakes.

Many platforms have formal programs for super-users (Reddit’s moderator program, Stack Overflow’s reputation system, etc.), which acknowledge that these keystone contributors function as an extension of the product team. They create value that the platform never could alone.

Growth Loops and Network Effects

Build loops where creator output drives acquisition, responsiveness drives retention, and both expand distribution. Loops beat funnels because they compound.

Designing for these growth loops means building in sharing features, referral incentives, and community features that let power users broadcast their activity to others. A classic example is how LinkedIn’s power users (recruiters and prolific networkers) create a loop: they send out lots of connection requests and messages (driving others to log in and respond), and they post content or job listings that bring passive users back to engage.

The lesson for builders is to architect systems where your 1% can amplify the growth by virtue of their high activity, effectively turning them into force-multipliers for network expansion and content creation. Growth loops powered by top contributors often outcompete expensive marketing, because they are organic and compounding.

Design for creation and connection: lower friction for content creation, offer analytics or personalized feedback to creators, and give them ways to connect with their audience. When power users thrive, they create the content that improves the experience for everyone else.

Crown the Core, Raise the Floor

So, is the 90/10 rule dead? In the sense of a predictable baseline, yes – community managers should expect something more like 99/1 and plan accordingly. But its core insight is alive and well: a minority of creators drive the majority of outcomes. Rather than fighting this law of nature, work with it consciously. Embrace your power users and design your product and incentives around them, while lowering barriers so newcomers join their ranks.

That’s the pragmatic middle ground: optimize for the head while investing in the tail.

The result is a thriving ecosystem of creators and their communities, where the most engaged 1% act as catalysts for growth, and thoughtful design ensures their success lifts, rather than eclipses, the 99%.