Table Of Links

4 RQ2: How do developers present their inquiries to ChatGPT in multi-turn conversations?

5 RQ3: What are the characteristics of the sharing behavior?

RQ3: What Are The Characteristics Of The Sharing Behavior?

Motivation: In RQ1 and RQ2, we focus on the content in shared conversations. In RQ3, we shift our attention to how and why developers share those conversations in GitHub pull requests and issues. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the characteristics associated with these sharing behaviors within the GitHub ecosystem, we propose three sub-RQs as follows:

– RQ 3.1 Rationale: What are the rationale behind the sharing of conversations? This question aims to uncover the underlying reasons for developers to share their conversations within GitHub PRs or issues.

– RQ 3.2 Location: Where are the links to these shared conversations located? This question examines where the links to shared conversations are posted in GitHub PRs and issues. GitHub PRs and issues contain different components, e.g., description, comment, and code review.

– RQ 3.3 Person: Who shared the conversations? This question investigates the involved developers, i.e., the roles and responsibilities of these developers within collaborative development environments like GitHub. Answering the above sub-RQs will reveal how developers leverage these shared conversations to enhance their collaboration work within Github. This insight will, in turn, indicate areas where ChatGPT can offer more targeted support to developers in these unique contexts. By understanding these dynamics, we can identify opportunities for ChatGPT and other FM-powered software development supporting tools, to contribute to enhanced productivity and foster stronger collaboration within open-source projects.

5.1 Approach

To answer the three sub-RQs, we determine the distribution of PRs and Issues on the combined PR and Issues datasets that are result of the data processing step. Out of 580 total shared conversations, 36.2% are from the PRs dataset and 63.8% are from Issues dataset. To achieve a statistically significant sample at a 95% confidence level and a margin of error of 5%, we employed stratified random sampling across the PR and Issue categories, selecting a subset of 250 conversations, i.e., 90 from PRs and 160 from Issues.

Subsequently, we applied stratified sampling to each of those subsetsj, using the criteria outlined in Table 1. This approach ensured the distribution of software task labels in our samples remained consistent with the findings from RQ1. Then we use the “MentionedURL” field in the conversation profile to collect a set of URLs pointing to the PRs and issues containing the selected conversations.

This process resulted in the 90 PRs and 160 issues we used for RQ3. For RQ3.1, similar to RQ2, we use open coding to manually label the rationale behind sharing by checking the usage of the shared conversations within the context of the PRs or issues containing them over three rounds:

– In the first round, three co-authors independently labeled 30 cases each from selected PRs and issues (in total 60). Through a follow-up discussion, the annotators developed a coding book containing six distinct labels.

– In the second round, two annotators independently labeled another 20 cases from GitHub PR and GitHub Issues, a total of 40 comments, based on the coding book established in the first round. The two annotators achieved an inter-rater agreement score of 0.78. They then discussed and resolved disagreements and refined the coding book.

– In the third round, the two annotators who participated in the second round continued and equally labeled the remaining cases based on the coding book.

For RQ3.2, we manually identified the location of links to shared conversations based on the types of provided content in a PR and issue. Specifically, for PRs, we assess whether the link is present in the PR title, description, comments, or code review comments. For issues, we determine if the link is included in the issue title, description, or comments. For RQ3.3, we manually identified the role of the developer who shared the conversation.

Specifically, we consider PR authors and code reviewers for PRs, and issue assignees, authors, and collaborators for issues. When we labeled the collected 90 PRs and 160 issues for RQ3.1, we found cases (those labeled as Others in Table 5.2.1) that could not be utilized in RQ3.2 and RQ3.3. Thus, we ended up with 85 PRs and 154 issues for RQ3.2 and RQ3.3.

5.2 Results

In the following paragraphs, we first summarize the distribution of categories for each sub-RQ in Section 5.2.1 and Section 5.2.2, and then present the findings of our cross sub-RQ analysis for RQ3 in Section 5.2.4.

5.2.1 RQ3.1 What are the rationale behind the sharing of conversations?

Table 5 details a taxonomy of the derived rationale from analyzing 184 shared conversations and their corresponding PRs and issues. It identifies the top three rationales for sharing conversations in both contexts: (P1) citing the conversation as a potential solution, (P2) referring to the conversation as a source of solution, and (P3) leveraging the conversation to bolster a claim. These rationales collectively represent the majority of sharing instances, accounting for 94% in selected DevGPT-PRs and 91% in DevGPT-Issues, respectively. Among the 250 analyzed cases, five in DevGPT-PRs and six in DevGPTIssues were categorized as Others due to challenges in identifying their specific purpose.

These challenges arose from several issues: 1) the removal of the link to the shared conversation, 2) the deletion of the linked pull request or issue, or 3) the content within the pull request or issue is in a language other than English. These factors contributed to the difficulty in discerning the intended use or contribution of the shared conversation in these instances. In one PR and 15 issues, developers only provided the URLs to the shared conversations without any explanation, forming the “Direct link” category. Below, we describe each category in more detail. We use “LINKTOCHAT” to refer to the omitted links to the actual shared conversation.

(P1) Reference to a source of solution: Developers reference shared conversations as the source of solutions in 37% of the cases within selected pull requests (with clear purpose), significantly more prevalent than in issues, where it accounts for 22%. This purpose often occurs when developers initiate aGitHub PR or issue following guidance or solutions suggested by ChatGPT. For instance, “Current solution is based on LINKTOCHAT. Now it seems work”. This observation indicates that ChatGPT has supported developers with their contributions to open-source projects. Furthermore, it reveals that developers are inclined to include additional context and details about their contributions by referencing their interactions with ChatGPT, which will enrich the collaborative development process by providing transparent insight into the reasoning and evolution of their contributions.

(P2) Reference to a potential solution: Beyond referencing solutions for already implemented code (P1), developers also refer to shared conversations as potential solutions. In pull requests, 33% of cases fall into this category, but it is significantly more prevalent in issues, accounting for 53%. The higher occurrence in issues is potentially due to their nature as places for exploring and debating prospective solutions aimed at issue resolution. In pull requests, we still find P2 a common category because shared conversations are leveraged to propose potential solutions for addressing code reviews, as exemplified in Figure 1.

(P3) Support a claim: Developers shared conversations to support their claims, arguments, or suggestions in 24% of PRs and 17% of identified issues with a clear purpose. For instance, “I have doubts about the utility of soft delete ... i consulted the chatgpt oracle, and it seems to not like soft deletion too: LINKTOCHAT”. Such instances demonstrate the strategic use of ChatGPT as an authoritative source or “oracle” to lend weight to a developer’s perspective or to resolve debates within the development process.

(P4) Answer a question: In 4% and 3% of the cases in PRs and issues, developers use the shared conversation as an answer to a question raised in the previous comment. For instance, a code reviewer in a pull request asked “This may need to be changed in transifex?...”. The pull request author answered: “I think it does sync. LINKTOCHAT ”.

(P5) Illustrate an example: In a few cases, one for PR and eight for the issue, developers use the shared conversation as an example to demonstrate a concrete example of their mentioned concepts. For instance, “We want a full exhaustive hierarchical enumeration of all the tasks a person might do on a computer. Similar to LINKTOCHAT but more exhaustive”.

5.2.2 RQ3.2 Where are the links to these shared conversations located? Table 6 shows the distribution of locations of links to shared conversations in Table 6 shows the distribution of locations of links to shared conversations in 85 pull requests and 154 issues.

5.2.3 RQ3.3 Who shared the conversations?

Table 7 shows the distribution of locations of links to shared conversations in 85 pull requests and 154 issues

and 154 issues.

5.2.4 Cross Sub-RQ Findings.

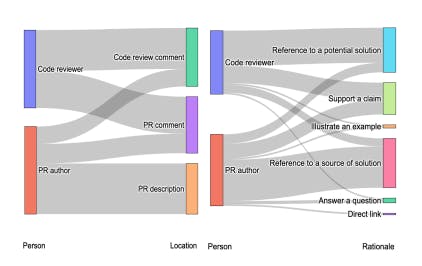

To further understand the sharing behaviors of developers, we conducted an in-depth analysis to investigate the relationships between three considered aspects, i.e., rationale, location, and person. Figure 6 shows two Sankey plots (“Person-Location” and “Person-Rationale” indicating the behavior patterns (where they share and why they share) of developers based on their roles in the pull requests. The width of the lines connecting these sets corresponds to the frequency of co-occurrence between the connected variables.

In the Person-Location plot, we observe that reviewers share conversations in code review comments and pull request comments with almost equal probability, 53%, and 47%, respectively. Authors usually share their conversations in the pull request description (58%) and in the pull request comment and code review comment with similar probability, 22% and 20%, respectively. In the Person-Rationale plot, we observed that reviewers usually share their conversations as a reference to a potential solution (P2) (55%), then to support a claim (P3) (28%), and last as a reference to a source of solution (P1) (13%).

Authors show a different sharing behavior; they mostly use shared conversations as a source of solution (P1) (58%), then support a claim (P3) (20%), and as a potential solution (P2) (13%). Figure 7 provides a detailed analysis of shared conversations within issues, employing a Person-Location and a Person-Rationale perspective. The Person-Location analysis reveals that collaborators and assignees exclusively share conversations in issue comments. Issue authors (reporters) predominantly share conversations in issue comments and descriptions, with a nearly even split of 49% for comments and 51% for descriptions. One issue author

even includes the link directly in the issue title. The Person-Rationale plot further dissects the motivations behind sharing conversations for different types of developers in issues. Issue authors primarily use shared conversations to highlight them as potential solutions (P2), counting for 41% of their shares.

This is followed by references to conversations as sources of solutions (P1) and support for claims (P3), which are shared with similar probabilities of 24% and 13%, respectively. Collaborators, on the other hand, are more inclined to share conversations as a potential solution (P2) in 69% of cases and, to a lesser extent, to support a claim (P3) at 21%. Assignees prefer sharing conversations as potential solutions (P2) in 50% of instances, with the remaining equally referencing other rationales (P1, P3 and P4) at 17% respectively.

The observed patterns of developers’ sharing behaviors reflect the distinct dynamics within pull requests and issues. In pull requests, authors are responsible for crafting comprehensive descriptions, whereas reviewers engage primarily through code review and pull request comments. This distinction is mirrored in their motivations for sharing links to conversations: authors often share to cite the origin of their implemented solution, while reviewers tend to share to introduce or suggest alternative solutions to the author.

In issues, the behavior diverges; authors actively contribute to the issue’s initial description and subsequent comments. Collaborators and assignees, in contrast, limit their contributions to comments. This dynamic sees authors using shared conversations as evidence supporting their proposed solutions and substantiating

their claims. Collaborators, on the other hand, frequently share conversations to present potential solutions or to bolster a claim. Our observations underscore the role of shared conversations in facilitating collaborative problem-solving, with each participant leveraging these exchanges according to their role and the unique collaborative needs of pull requests and issues.

Authors

- Huizi Hao

- Kazi Amit Hasan

- Hong Qin

- Marcos Macedo

- Yuan Tian

- Steven H. H. Ding

- Ahmed E. Hassan

This paper is