This is a Plain English Papers summary of the research paper, Harder Is Better: Boosting Mathematical Reasoning via Difficulty-Aware GRPO and Multi-Aspect Question Reformulation.

The hidden imbalance in how AI learns math

Most AI training for math treats all problems the same way. A simple arithmetic problem gets the same learning signal as a complex multi-step proof. This turns out to be a critical oversight.

The standard approach uses reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards (RLVR). The AI solves problems, gets feedback on whether it's correct, and adjusts its reasoning based on that signal. This works reasonably well. But there's a subtle architectural flaw in the most popular method for this kind of training: Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO).

When GRPO learns from a batch of problems, it pools information across all of them to compute how much to update the model's policy. For hard problems, the outcomes are naturally messier and more varied. Sometimes the model gets lucky and solves it anyway, sometimes it fails for different reasons. This variance doesn't disappear when you pool the data. Instead, it dilutes the learning signal from hard problems relative to easy ones. The algorithm ends up taking smaller steps in the direction of "get better at hard problems," even though those are the problems that matter most for genuine mathematical reasoning.

This is consequential. A model trained on a mix of easy and hard problems will naturally become expert at the easy ones. It's not that the algorithm refuses to learn from hard problems, it's that the learning signal is systematically weaker, buried in noise. You could have 20% hard problems in your training set, but you're learning from them at perhaps 10% the rate you should be.

Why equal treatment fails

Here's what happens in practice. Imagine a student learning chess with a fixed-size feedback mechanism. A simple tactical error gets a clear signal: "you missed this fork." A complex positional mistake buried in a 30-move sequence gets the same sized correction, but that correction is now lost in the complexity. The feedback doesn't match the problem's importance.

Scale this across thousands of training examples. The algorithm's "pen" for marking mistakes has a fixed size. On simple problems, that mark is proportional and clear. On complex problems, it's proportional and gets diluted. The result is that a model becomes unreliably good at harder reasoning tasks. It might handle 90% of easy problems but only 40% of hard ones, when ideally the gap would be much smaller.

This matters because hard problems in mathematics are where real understanding lives. If a model can do basic algebra but struggles with multi-step reasoning, it hasn't learned to think mathematically at all, it's memorized patterns. The current training approach doesn't just struggle with this, it's structurally biased against improving it.

Two improvements that need each other

The paper proposes fixing this from two angles simultaneously. You can improve the algorithm so it learns better from hard problems, but if you're still feeding it the same easy problems, you're still learning mostly about easy problems. Conversely, you could make all problems harder, but if the algorithm hasn't learned to extract insight from that difficulty, you're just creating noise.

The solution is a framework called MathForge. It has two parts that form a feedback loop. On the data side, a technique called Multi-Aspect Question Reformulation (MQR) creates harder versions of existing problems. On the algorithm side, Difficulty-Aware Group Relative Policy Optimization (DGPO) ensures the model actually learns effectively from those harder problems. The two strengthen each other: harder problems give more signal to learn from, and a smarter learning algorithm extracts that signal more effectively, which justifies creating even harder problems.

Making problems harder without changing the answer

Let's say you have a straightforward question: "What is 25% of 80?" The answer is 20. You can't just change it to "What is 17% of 143?" because that breaks the entire system. The answer key no longer works.

Instead, you reformulate it while keeping the core intact. "A store is having a 25% off sale on an $80 jacket. You also have a coupon for an additional 10% off the sale price. What is the final price?" The original question is still there, but now it requires multiple reasoning steps, holds more intermediate values in working memory, and demands better problem decomposition. The correct answer is still 20, but getting there requires deeper thinking.

MQR expands problems across multiple dimensions. It doesn't just add steps, it adds irrelevant information that needs filtering, introduces constraints that require rethinking, or presents the problem in an unusual format. Think of it as remixing a problem in different arrangements while preserving what makes it correct.

This matters because data augmentation already exists in the field. Most methods rephrase questions to add variety: same problem, different wording. But variety and difficulty aren't the same thing. A rephrased but simple problem teaches the model to recognize and regurgitate easy patterns faster, not to think harder. MQR specifically targets intrinsic difficulty, which is what actually builds reasoning capability.

Teaching the algorithm to weight hard problems correctly

Better data is useless if the algorithm doesn't prioritize it. DGPO fixes the algorithm itself in two ways.

First, it rebalances how the algorithm pools information from different problems. Instead of treating all problems equally when computing the learning signal, DGPO identifies which problems are hard (using metrics like success rates across training iterations) and upweights them in the group statistics. This prevents hard problems from getting diluted in the average.

Second, it applies an additional per-problem weight after computing advantages. A hard problem that the model got wrong gets a larger policy update than an easy problem that the model got wrong. This sounds simple, but it requires careful integration into the algorithm's core design. Standard policy optimization works because it's finely balanced. If you naively multiply weights without rethinking the whole mechanism, you can make learning unstable or biased. DGPO preserves the theoretical properties that make the learning work while ensuring hard problems get their due weight.

The result is that when the model fails on a hard problem, the algorithm takes a bigger step to fix that failure. When it succeeds on a hard problem, the success reshapes the model's thinking more significantly. Easy problems still get learned, but they're no longer the center of gravity.

The loop that amplifies everything

Here's where the two improvements multiply each other's effectiveness. MQR creates harder versions of problems with more diverse solution paths and subtler failure modes. DGPO, knowing which problems are hard, learns from these diverse failures more effectively. As the model improves on hard problems, MQR can identify which reformulations actually increased difficulty in meaningful ways, the ones where the model still struggles. DGPO then learns even more efficiently from the refined hard problems. Each cycle tightens the loop.

This is the difference between a method and a framework. A method optimizes one thing. A framework optimizes the interactions between things. MathForge is built as an intentional loop where each component makes the other more valuable.

Validation on real problems

Testing happened on actual mathematical reasoning benchmarks: problems from graduate-level entrance exams, competition mathematics, and reasoning tasks that are genuinely difficult. The core question is straightforward: Does a model trained with MathForge get better at these problems?

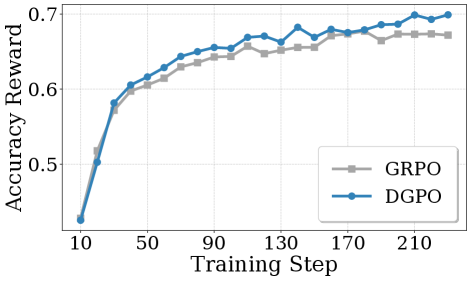

Accuracy rewards across difficulty levels, comparing MathForge to baseline GRPO, showing larger improvements on harder problems

MathForge (DGPO + MQR) shows significantly larger accuracy gains on harder problems compared to standard GRPO, with the gap widening as problem difficulty increases.

The pattern is clear. MathForge outperforms existing methods, and crucially, the improvement is largest on the hardest problems. Easy problems? The model was already competent there. Medium problems? Modest gains. Hard problems? Substantial gains. This is the exact profile you'd want to see. If the method was just adding noise or overfitting, you'd see different patterns.

Testing what happens when you remove pieces confirms the synergy story. Remove DGPO but keep MQR? The model improves, but not as much as it could. Remove MQR but keep DGPO? Again, improvement but suboptimal. Use both? Best results. This ablation proves the two parts really do need each other.

Comparison of output reasoning length between DGPO and baseline approaches. Harder problems naturally induce longer, more detailed reasoning. DGPO enables the model to sustain this longer reasoning without degradation.

Training curves showing DGPO learns faster on hard problems while maintaining performance on easy problems. Training efficiency: DGPO achieves faster convergence on difficult problems while preserving performance on the full distribution.

Evaluation results demonstrating the consistency of MathForge improvements across multiple mathematical reasoning benchmarks. Across multiple evaluation benchmarks, the improvements hold consistently, validating that MathForge addresses a fundamental limitation rather than dataset-specific quirks

Why this matters beyond math

MathForge reveals something important about how AI systems develop capability. When you optimize for easy wins, you build a system that's good at easy things. When you optimize for hard things, you become good at everything, including the easy parts (which are now trivial). The research suggests that AI training methods have been implicitly biased toward shallow patterns.

This connects to broader work on how optimization objectives shape learned representations. Research on group distributionally robust optimization in reinforcement learning has explored similar themes about which problems deserve more learning weight. MathForge applies this thinking directly to the problem of mathematical reasoning.

The framework also relates to recent work on accelerating GRPO-style training, which has separately explored how to make policy optimization more efficient. MathForge's contribution is showing that efficiency gains and capability improvements can be aligned when you target the right problems.

The principles might extend beyond mathematics. Anywhere there's a skill hierarchy from novice to expert, the same logic applies: training methods should emphasize the hard, not the easy. MathForge is specifically about mathematical reasoning, but it's a proof of concept for a broader principle about how to build systems with genuine capability rather than just pattern recognition.

If you like these kinds of analyses, join AIModels.fyi or follow us on Twitter.