This is a Plain English Papers summary of a research paper called OpenVision 3: A Family of Unified Visual Encoder for Both Understanding and Generation.

Overview

- OpenVision 3 is a family of visual encoder models that handle both understanding and generation tasks with a single architecture

- The system uses a unified tokenizer approach that converts images into a common representation

- Multiple model sizes are available, allowing deployment across different computational requirements

- The architecture builds on previous OpenVision work to improve efficiency and capability

- Training combines vision-language pretraining with generative objectives

Plain English Explanation

Most AI vision systems today fall into two camps. One group is designed to understand images—looking at a photo and describing what's in it. Another group generates images from descriptions. OpenVision 3 takes a different approach: it builds a single encoder that does both jobs well.

Think of it like a universal translator. Instead of having separate translators for English-to-French and French-to-English, you have one system that understands both languages and can work in either direction. The key innovation here is how the system converts images into a standardized format called tokens.

The unified tokenizer is crucial. Rather than having different ways to represent images for understanding versus generation, OpenVision 3 uses the same token system for everything. This means the encoder learns representations that are genuinely useful across multiple tasks, not just optimized for one specific job. It's like learning a skill that makes you better at related activities without needing separate training for each one.

The research demonstrates that you don't need separate specialized models. A single well-designed encoder can achieve strong results on both understanding tasks (like image captioning or visual question answering) and generation tasks (like creating images from text descriptions). This has practical benefits: fewer models to maintain, easier to update, and faster to deploy.

Key Findings

- OpenVision 3 achieves competitive performance on vision-language understanding benchmarks while also supporting image generation capabilities

- The unified tokenizer approach reduces redundancy compared to maintaining separate understanding and generation models

- Multiple model sizes in the family show that the approach scales effectively from smaller to larger models

- Performance on downstream tasks demonstrates that the shared representation learned during pretraining transfers well to both understanding and generation applications

Technical Explanation

OpenVision 3's architecture centers on a visual encoder that processes images into token representations. These tokens serve as an intermediate language that any downstream model can work with, whether that model is designed for understanding or generation tasks.

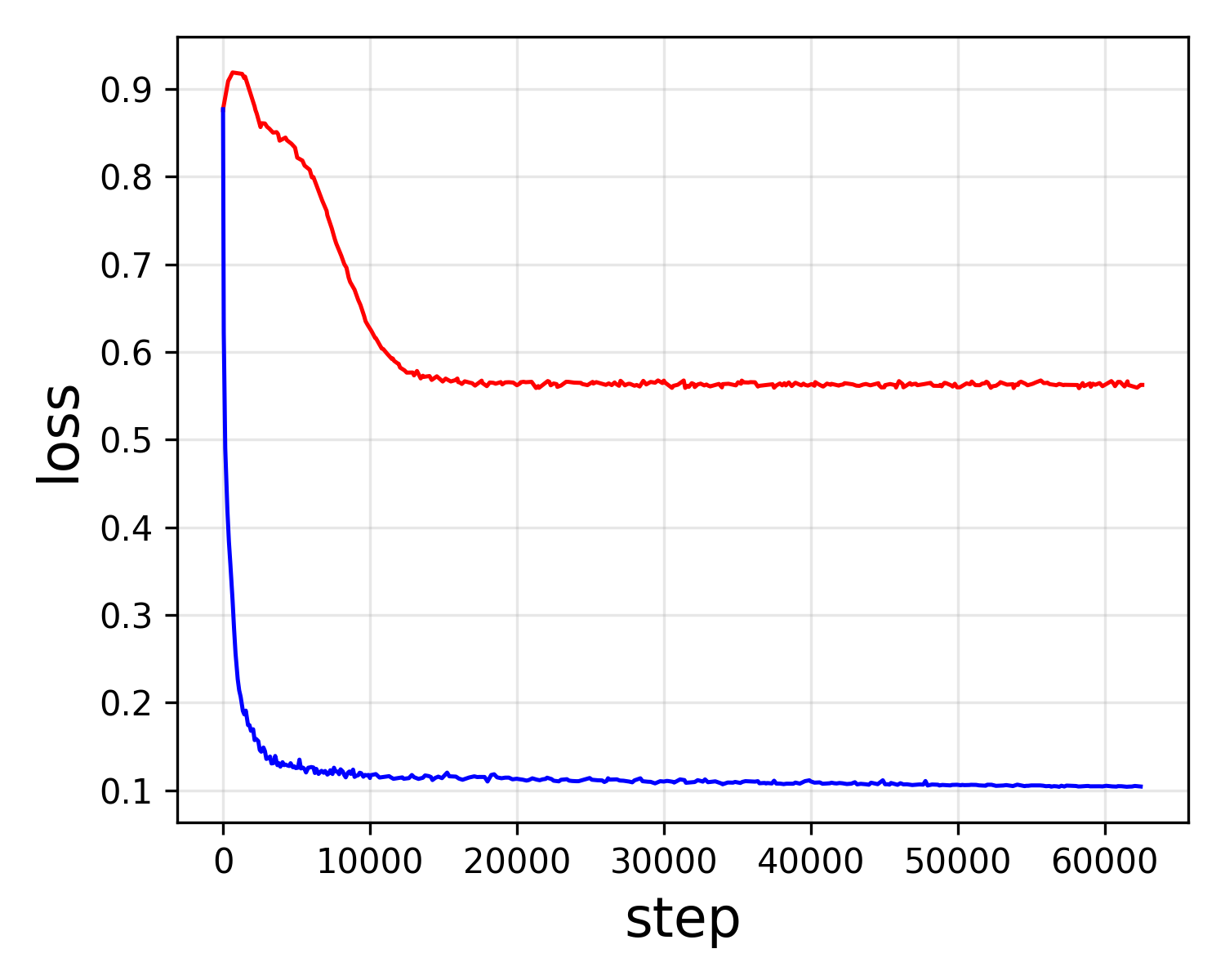

The training process combines vision-language pretraining with generative objectives. During vision-language pretraining, the model learns to align visual representations with text descriptions. This happens through contrastive learning or similar techniques that encourage the encoder to produce representations where images and their descriptions are close together in the learned space.

The generative component trains the encoder to produce tokens suitable for reconstruction tasks. This means the tokens must preserve enough visual detail to allow a decoder network to recreate the original image. This requirement forces the encoder to learn richer, more detailed representations than it would if only trained for understanding tasks.

The tokenizer design treats discrete tokens as a vocabulary—similar to how language models work with word tokens. Every image gets converted into a sequence of these tokens. The same vocabulary works for both understanding and generation pipelines. When understanding an image, downstream models read these tokens. When generating an image, decoder networks read the tokens and reconstruct visual content.

The research includes multiple model sizes within the OpenVision 3 family. Larger models provide better performance for complex tasks. Smaller models offer faster inference and lower computational requirements. This flexibility means organizations can choose the model size that matches their constraints and requirements.

Critical Analysis

The paper's HTML structure is incomplete, making it difficult to fully assess all experimental details and performance comparisons. The table of contents shows sections on related work and methodology, but the complete technical details and comprehensive benchmark results are not visible in the provided content.

A key question for this approach: does training a single encoder for both understanding and generation force meaningful compromises? The unified tokenizer might create bottlenecks where the representation format that works best for understanding differs from what generation tasks need. The paper should provide detailed ablation studies comparing this unified approach against optimized single-task encoders, though these details are not apparent in the available content.

The scalability claims across model sizes deserve scrutiny. It's one thing to show that a family of models maintains competitive performance; it's another to prove they're genuinely more efficient than training purpose-built models. The resource costs and training time comparisons would strengthen these claims.

The integration with existing vision-language pretraining approaches and whether OpenVision 3 truly advances beyond prior methods needs careful examination. The related work section indicates this builds on previous OpenVision generations, so the specific improvements and innovations over those systems matter for evaluating the contribution.

It would help to see performance breakdowns showing whether the unified approach trades off capability in either understanding or generation compared to specialized alternatives. The paper should address when this unified approach works well and when practitioners might prefer specialized models instead.

Conclusion

OpenVision 3 represents a pragmatic approach to visual AI: rather than maintaining separate systems for understanding and generation, use a single encoder architecture with a carefully designed unified tokenizer. This consolidation offers engineering benefits and suggests that images can be effectively represented in a way that serves multiple downstream tasks simultaneously.

The significance extends beyond just convenience. The finding that a single visual encoder can handle both understanding and generation indicates something useful about how images should be represented for AI systems. It suggests these tasks share more fundamental structure than treating them as completely separate problems would imply.

For practitioners, the family structure across different model sizes addresses a real need: matching model capability to computational constraints without having to train entirely new systems. This could accelerate adoption of multimodal capabilities in settings where specialized models seemed impractical.

The work connects to broader trends in unified video understanding and generation and the development of semantic encoders across visual domains. As AI systems become more capable, the ability to share representations across tasks becomes increasingly valuable. OpenVision 3 demonstrates this principle at scale for visual tasks, offering a template for how future multimodal systems might be structured.

If you like these kinds of analyses, join AIModels.fyi or follow us on Twitter.