In a cellar deep inside Soviet-era Prague, hidden from the prying eyes of the secret police, the frantic clatter of typewriter keys suddenly stopped. The writer took the carbon copies of the book he had just finished transcribing and handed them to my father, who at the time was no older than I am as I write this.

My father’s task was to bind the pages into makeshift paperbacks and distribute them in secret—a dangerous undertaking that could result in imprisonment or worse. It was a laborious process: the typewriter was barely strong enough to punch through two carbon copies at a time, so each transcription produced at most three copies legible enough to distribute. What made my father and his accomplice’s efforts stand apart was not merely the considerable risk they took, but the surprising title they chose to champion. Instead of smuggling subversive political literature critical of the communist regime or banned religious texts, their clandestine efforts went toward spreading Pán Prstenů—Czech for The Lord of the Rings.

Much has changed since those times. Prague is no longer under communist rule, and my father no longer fears that his love of fantasy literature might land him in a political prison. However, the specter of censorship and the underlying motives that prompted authoritarian governments to ban even seemingly benign works of fiction remain as relevant today as they were then.

Indeed, modern digital technology has given censors unprecedented power over information flow, while simultaneously creating new, more sophisticated methods of content manipulation that make the heavy-handed bans of the past seem quaint by comparison.

Tolkien’s Unintended Geography

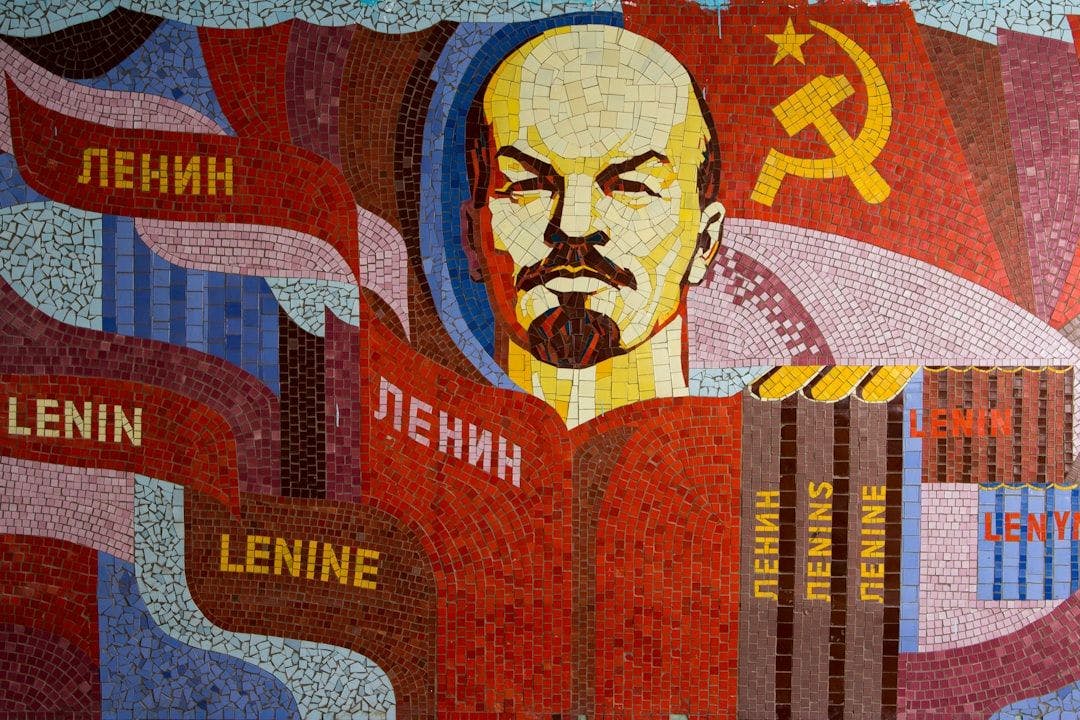

For a regime whose censorship apparatus was often characterized by its blunt, heavy-handed approach, the reasoning behind banning J.R.R. Tolkien’s celebrated trilogy was surprisingly nuanced. As one might expect from high fantasy literature, Tolkien weaves a grand narrative of conflict between the forces of good and evil, set in his meticulously crafted fictional world that became synonymous with the fantasy genre: Middle-earth.

On the surface, none of this should have troubled Soviet cultural bureaucrats—after all, the story contains no explicit political commentary, no critique of socialism, and no references to contemporary geopolitics.

The problem lay in geography. The land of Mordor—stronghold of the dark forces under the command of Sauron—was situated to the east, mirroring the geographic position of the Soviet bloc relative to Western Europe. Meanwhile, the realms inhabited by humans, elves, and dwarves (the heroic forces of good) were located to the west, just as the Soviet Union’s ideological nemesis, the United States and its NATO allies, lay westward from the communist sphere of influence. This unflattering geographical symbolism, whether intentional or coincidental, was sufficient to render The Lord of the Rings trilogy ban-worthy in the eyes of Soviet censors (Loseff, 2001).

The irony, of course, is that Tolkien began writing The Lord of the Rings in the 1930s, well before the Cold War’s ideological battle lines were clearly drawn. His placement of evil in the east likely drew more from classical Western literary traditions and Biblical symbolism than from any prescient political commentary (Shippey, 2005). Yet, this coincidence of geography proved potent enough to transform a work of fantasy into a potential instrument of Western propaganda in the paranoid calculus of totalitarian censorship.

We can debate whether banning a work of fiction whose resemblance to Cold War dynamics was likely only incidental constituted an overreaction, or whether it represented a rational necessity for an oppressive government determined to maintain power through ideological control. However, the Soviet approach raises an intriguing question: if only a minor aspect of a work proves objectionable, why not employ a more surgical approach to censorship?

Theoretically, the Soviet Union could have mandated that publishers relocate Mordor and all references to it westward, thereby inverting the troublesome symbolism and transforming Tolkien’s narrative into an inadvertent endorsement of communist geography. Such editorial manipulation would have turned the West into the source of evil while positioning the East as humanity’s salvation.

Banning the book outright was a missed opportunity to conscript comrade Gandalf into the Soviet propaganda machine. Over half a century later, the Chinese Communist Party would not pass up on a similar opportunity.

Digital Age Censorship

Contemporary audiences might express surprise at finding the 1999 cult classic Fight Club available on mainstream Chinese streaming platforms. David Fincher’s film glorifies everything that law-and-order regimes typically despise: rule-breaking, violence, anti-establishment sentiment, and anarchistic destruction of social institutions.

The movie’s unnamed protagonist, portrayed by Edward Norton, abandons his conventional yet spiritually hollow existence as an automobile recall specialist to pursue a path of deliberate violence—often self-inflicted—and uses his influence among like-minded dissidents to strike at the very foundations of capitalist society by orchestrating the destruction of major financial institutions.

The reason Fight Club gained approval for Chinese distribution has less to do with censorial leniency than with the sophistication of modern content manipulation techniques. Rather than implementing an outright ban—the blunt instrument favored by earlier authoritarian regimes—Chinese censors demonstrated remarkable creativity by surgically altering the film’s conclusion to align with state-approved messaging (Kokas, 2017).

The Fight Club that reaches Chinese audiences differs dramatically from the original in its final moments. Fincher’s version concludes with a series of spectacular explosions as skyscrapers housing major credit card companies collapse in perfect synchronization, marking the triumphant completion of Project Mayhem’s scheme to reset the global economy through calculated chaos. The protagonist and his love interest, Marla Singer, watch hand-in-hand as the urban landscape transforms before their eyes, suggesting that destructive rebellion can lead to romantic fulfillment and societal renewal.

In the Chinese version, however, this climactic sequence vanishes entirely. Instead, viewers encounter a text overlay informing them that law enforcement authorities successfully foiled the terrorist plot and that the protagonist was promptly apprehended and subjected to legal consequences. The film’s original defiant conclusion—one that celebrated the power of individual rebellion against systemic oppression—becomes transformed into a cautionary tale that reinforces state authority and warns potential dissidents that sophisticated criminal enterprises inevitably face detection and punishment (Zhang, 2022).

This editorial intervention represents a paradigmatic shift in censorship methodology. Where earlier authoritarian systems relied primarily on prohibition and suppression, contemporary digital censorship increasingly employs content modification to transform potentially subversive material into propaganda that serves state interests.

Fight Club exemplifies a broader trend in digital-age content control, but it is far from unique in receiving such treatment. Chinese streaming platforms routinely alter foreign films and television series to conform to government guidelines, often in ways that fundamentally transform their thematic content (Xu, 2021).

Bohemian Rhapsody, the biographical film about Queen frontman Freddie Mercury, saw all references to Mercury’s homosexuality excised from its Chinese release, effectively erasing a central element of both the character’s identity and the film’s narrative arc (Reuters, 2019).

These examples illustrate how modern censorship has evolved beyond simple prohibition toward sophisticated content manipulation that maintains the veneer of cultural engagement while fundamentally altering meaning. This approach offers several advantages over traditional banning: it avoids the international criticism that typically accompanies high-profile censorship decisions, maintains economic relationships with foreign content producers, and provides domestic audiences with modified versions of popular international media that subtly reinforce rather than challenge state ideology.

Where earlier authoritarian systems relied primarily on prohibition and suppression, contemporary digital censorship increasingly employs content modification to transform potentially subversive material into propaganda that serves state interests.

When Reality Becomes Malleable

The digital revolution has not merely changed the methods of censorship; it has expanded its scope and effectiveness. Where Soviet censors required armies of bureaucrats to monitor typewriters and printing presses, contemporary authoritarian systems employ artificial intelligence and automated content filtering to surveil and control information flows at an unprecedented scale (Roberts, 2018).

China’s “Great Firewall” represents perhaps the most sophisticated example of technological censorship infrastructure ever constructed. This system combines traditional content blocking with real-time content modification, keyword filtering, and predictive algorithms that can identify and suppress potentially problematic material before it gains widespread circulation (King, Pan, & Roberts, 2013).

The system’s effectiveness extends beyond mere prohibition to encompass what scholars term “manufactured consent”—the creation of artificial online environments that give users the illusion of free discourse while carefully constraining the boundaries of acceptable opinion (Tufekci, 2017).

Social media platforms, originally heralded as democratizing technologies that would undermine authoritarian control, have instead become powerful instruments of state influence. Governments worldwide have learned to weaponize these platforms’ own content moderation systems, using coordinated reporting campaigns, bot networks, and algorithmic manipulation to suppress dissenting voices while amplifying preferred narratives (Bradshaw & Howard, 2019).

The concept of “post-truth” politics—wherein emotional appeal and personal belief assume greater importance than objective facts—has created new opportunities for sophisticated censorship and propaganda (d’Ancona, 2017). In this environment, the line between information and disinformation becomes increasingly blurred, allowing authoritarian actors to exploit uncertainty and confusion rather than simply suppressing inconvenient truths.

This phenomenon extends beyond traditional authoritarian states to encompass democratic societies where polarization and media fragmentation have created echo chambers that function as de facto censorship systems. When individuals primarily consume information that confirms their existing beliefs, external censorship becomes less necessary—citizens effectively censor themselves by avoiding challenging perspectives (Pariser, 2011).

The result is a landscape where multiple, contradictory versions of reality can coexist within the same society, each supported by its own information ecosystem and resistant to external contradiction.

The influence of sophisticated censorship techniques extends far beyond the borders of authoritarian states. When Chinese authorities demand content modifications as a condition of market access, international entertainment companies face a choice between artistic integrity and economic opportunity. Increasingly, studios opt for self-censorship during the production process, creating films designed from inception to satisfy Chinese regulatory requirements (Kokas, 2017).

This dynamic creates what scholars term “censorship contagion”—the spread of restrictive content standards from authoritarian markets to global media production (Rosen, 2010). When major studios alter their creative processes to accommodate Chinese censorship requirements, audiences worldwide receive entertainment products shaped by authoritarian preferences, even if they live in societies with strong free speech protections.

Similar dynamics operate in the technology sector, where platforms seeking access to restricted markets often implement censorship capabilities that can subsequently be deployed more broadly. The infrastructure of digital control, once established, proves remarkably adaptable to new contexts and applications (Zuboff, 2019).

Resistance and Adaptation

Despite technological advances that favor censorship, resistance continues to evolve alongside oppression. Where my father relied on carbon paper and manual distribution networks, contemporary dissidents employ encrypted messaging applications, blockchain-based publishing platforms, and decentralized communication networks that prove increasingly difficult for authorities to control (Thornton, 2021).

The same technologies that enable sophisticated censorship also create new possibilities for circumvention. Virtual private networks (VPNs) allow users to bypass geographic content restrictions, while peer-to-peer networks enable information sharing that requires no central authority to suppress. Cryptocurrency systems provide censorship-resistant methods for funding dissident activities, while advanced encryption makes surveillance increasingly difficult and expensive (Rogaway, 2015).

However, this technological arms race between censors and dissidents should not obscure the fundamental asymmetry in resources and capabilities. While individual activists may employ sophisticated tools to evade detection, state actors possess vastly superior resources for developing countermeasures and compelling platform cooperation.

The contrast between my father’s clandestine typewriter sessions and contemporary digital content manipulation reveals both the evolution and the persistence of censorship as a tool of social control. Where earlier authoritarian systems relied on prohibition and punishment, modern approaches increasingly emphasize modification and manipulation—transforming potentially subversive content into propaganda that serves state interests.

This shift from suppression to manipulation represents a fundamental change in the nature of censorship itself. The heavy-handed bans that made heroes of underground publishers and samizdat distributors have given way to subtler forms of control that maintain the appearance of cultural freedom while carefully constraining its substance.

Yet, the underlying dynamic remains unchanged: those in power seek to control information flows to maintain their position, while those who value intellectual freedom continue to develop methods of resistance and circumvention. The technologies change, but the fundamental tension between authority and liberty persists across generations and political systems.

The story of The Lord of the Rings in communist Prague and Fight Club in contemporary China illustrates this continuity while highlighting the increasing sophistication of censorship techniques. As we navigate an information landscape shaped by algorithmic filtering, deepfake technology, and artificial intelligence, the lessons learned in that Prague cellar become more relevant than ever: the price of intellectual freedom is eternal vigilance, and the tools of resistance must evolve as rapidly as the methods of oppression.

In our post-truth world, where reality itself becomes a contested concept, the stakes of this struggle extend beyond the preservation of individual works of art or literature to encompass the very possibility of shared factual understanding upon which a democratic society depends.

The typewriter keys that once echoed through my father’s Prague cellar may have fallen silent, but their message resonates more urgently than ever: the freedom to think, to read, and to share ideas remains humanity’s most precious and precarious achievement.

References

- Bradshaw, S., & Howard, P. N. (2019). The Global Disinformation Order: 2019 Global Inventory of Organised Social Media Manipulation. Oxford Internet Institute.

- Brzeski, P. (2021, November 8). China Reportedly Won't Release Marvel's 'Eternals' Over Director Chloe Zhao's Past Comments. The Hollywood Reporter.

- d'Ancona, M. (2017). Post-Truth: The New War on Truth and How to Fight Back. Ebury Press.

- King, G., Pan, J., & Roberts, M. E. (2013). How Censorship in China Allows Government Criticism but Silences Collective Expression. American Political Science Review, 107(2), 326-343.

- Kokas, A. (2017). Hollywood Made in China: How Chinese Money Is Reshaping the Film Industry in East and West. University of California Press.

- Loseff, L. (2001). On the Beneficence of Censorship: Aesopian Language in Modern Russian Literature. Translated by Jane Bobko. Slavica Publishers.

- Pariser, E. (2011). The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You. Penguin Press.

- Reuters. (2019, March 15). China Censors Gay Scenes from 'Bohemian Rhapsody' Screenings. Reuters.

- Roberts, M. E. (2018). Censored: Distraction and Diversion Inside China's Great Firewall. Princeton University Press.

- Rogaway, P. (2015). The Moral Character of Cryptographic Work. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2015/1162.

- Rosen, S. (2010). Chinese Cinema's International Market. In Art, Politics and Commerce in Chinese Cinema (pp. 17-41). Hong Kong University Press.

- Shippey, T. (2005). The Road to Middle-earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology. Revised Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Thornton, P. M. (2021). The Digital Disruption of China's Censorship Regime. Asian Survey, 61(4), 677-701.

- Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. Yale University Press.

- Xu, B. (2021). Learning Empire: Globalization and the Chinese Quest for World-Class Universities. Harvard University Press.

- Zhang, L. (2022). Censorship and Content Modification in Chinese Digital Media Markets. Journal of Contemporary China, 31(133), 89-105.

- Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. PublicAffairs.