1. Why bother combining Prompts and Pandas?

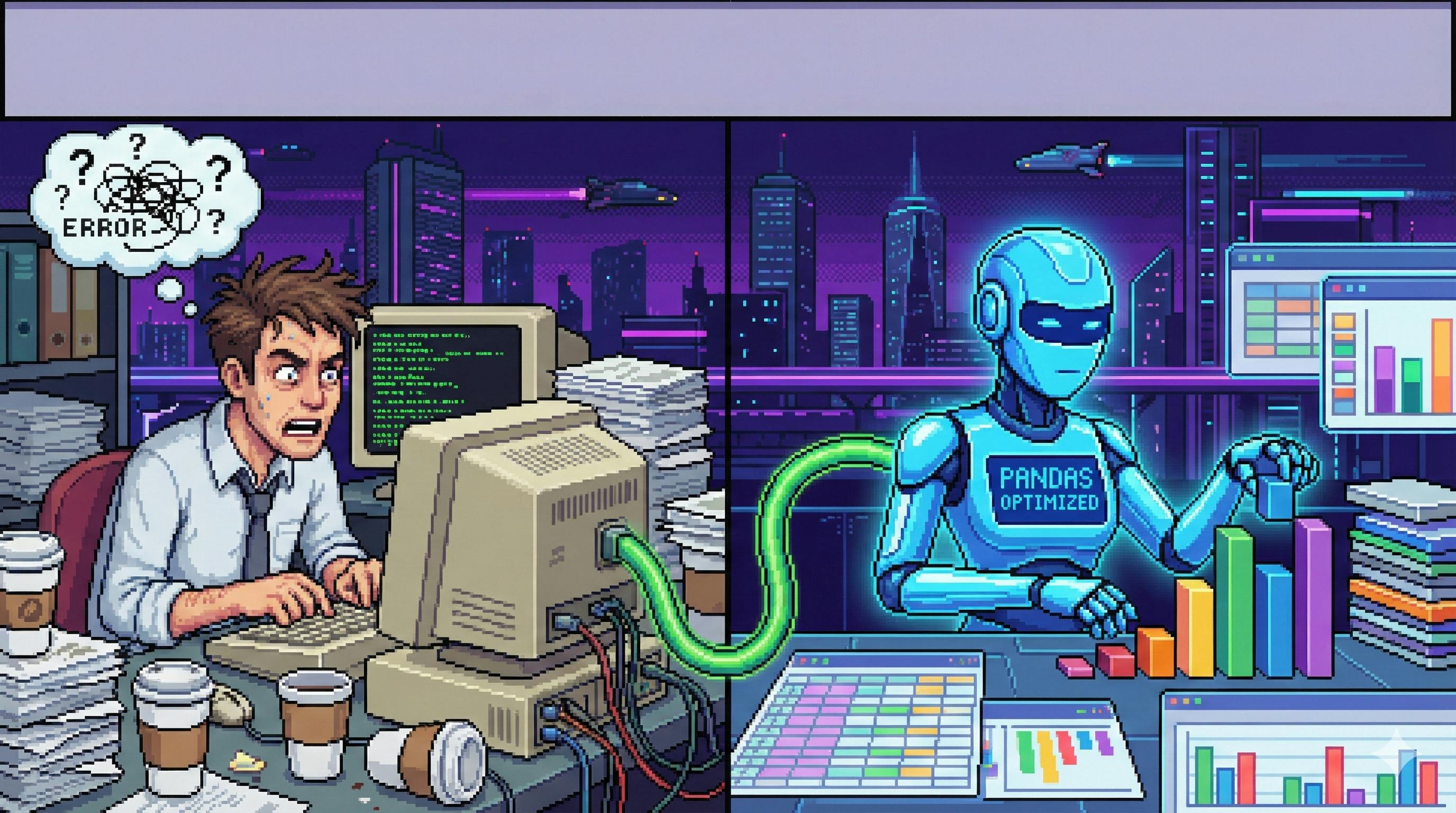

Pandas is powerful, but the developer experience is… let’s say “1990s Linux energy”:

- You remember half the API, mis‑remember the other half.

.groupby(),.merge(),.agg()work differently than you think.- Every non‑trivial task ends in a tab explosion: docs, blogs, old notebooks, Slack messages from That One Data Person.

Meanwhile, modern LLMs like GPT‑5.1 Thinking, Claude 3.5, Gemini 3, etc. are very, very good at:

- remembering weird API details,

- generating boilerplate,

- explaining errors,

- and turning fuzzy business asks into specific steps.

So instead of:

“How do I do a multi‑index groupby across three tables and then calculate a 7‑day rolling churn rate? Let me google that for an hour…”

…you can do:

“Here’s my schema, here’s my definition of churn, here’s roughly what I want. Give me Pandas code, explain the logic, and make sure it scales to 5M rows.”

The point is not “let the AI do all the work”. The point is “I keep my brain for the domain logic; the model does the annoying Pandas ceremony.”

This article walks through how to prompt in a way that produces code you can actually run, tweak, and trust.

2. Six places where “Prompt + Pandas” is a cheat code

You don’t need an LLM for df.head(). You do need it when your brain is melting.

Here are 6 high‑leverage scenarios:

|

Scenario |

What you have |

What you want from the model |

Who it especially helps |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Code generation |

Clear data requirement, fuzzy API memory |

Runnable Pandas code from raw data to final output |

Beginners, domain experts who “sort of” code |

|

Code explanation |

A mysterious script from a colleague |

Plain‑English explanation, parameter hints, data flow |

New joiners, code reviewers |

|

Code optimisation |

Working but slow code |

Vectorised / groupby‑based version, less loops |

Anyone with 1M+ rows |

|

Error debugging |

Stack traces, half‑broken notebook |

Root cause + patch + sanity checks |

Everyone at 2 a.m. |

|

Requirement translation |

Vague business ask |

Concrete analysis plan → Pandas steps → code |

Data/BI folks embedded in business teams |

|

Batch automation |

Repetitive monthly/weekly tasks |

Parameterised, loop‑able pipelines, maybe functions |

People cranking reports on a schedule |

The rest of the article is about designing prompts that land you in the right‑hand column instead of generating broken pseudocode.

3. Five principles of high‑signal Pandas prompts

Think of your prompt as a super‑compressed spec. GPT‑5 can interpolate missing bits, but if you leave too much out, you’ll get fragile or wrong code.

My practical mental model:

The model can’t see your data. All it sees is your description.

So give it just enough to be useful, not so much that it becomes a novel.

Principle 1: Describe the data, not just the wish

Bad:

“Write Pandas to compute each user’s average spend.”

The model doesn’t know:

- what the file is called,

- what the columns are,

- which one is “user”, which one is “money”.

Good:

I have a CSV at ./data/transactions_2024.csv with these columns:

- customer_id: string, unique user identifier

- txn_timestamp: string, e.g. "2024-05-01 09:30:00"

- gross_amount: float, transaction value in GBP

- region: string, like "England", "Scotland", "Wales"

Write Pandas code to:

1. Read the CSV.

2. Compute each customer's average gross_amount (call it avg_spend).

3. Sort by avg_spend descending.

4. Save to ./output/customer_avg_spend.csv.

You didn’t drown the model in detail, but you told it:

- real column names,

- types,

- file locations,

- and the output path.

That’s enough for GPT‑5 to produce drop‑in code instead of “replace_this_with_your_column_name” nonsense.

Principle 2: Nail the goal and the output format

Models are surprisingly good at filling in gaps, but they’ll often stop at 80%:

“Here’s your groupby; writing to CSV is left as an exercise :)”

Be explicit about both:

- the operation (“filter between dates, group by region, derive 3 metrics”), and

- the form you want at the end (“DataFrame with X columns” and “save as Excel/CSV/Parquet, path = …”).

Example prompt:

I have a DataFrame called df with columns:

- event_date: datetime, e.g. "2024-03-15"

- region: string, e.g. "North", "South"

- revenue: int

Write Pandas code to:

1. Filter rows where event_date is in March 2024.

2. Group by region and calculate:

- total_revenue (sum of revenue)

- event_count (number of rows)

3. Add a column avg_revenue_per_event = total_revenue / event_count

with 2 decimal places.

4. Produce a new DataFrame with columns:

region, total_revenue, event_count, avg_revenue_per_event

5. Save it to ./reports/region_revenue_202403.xlsx, sheet name "region_stats".

This is where GPT‑5 shines: you give it a bullet‑point storyboard, it gives you consistent code plus often some nice extras (e.g. validation prints).

Principle 3: Inject the business rules, not just schema

The model understands Pandas. It does not understand “active customer”, “churned user”, or “suspicious transaction” unless you explain it.

Example (good):

I work on a subscription product. DataFrame: events_df

Columns:

- user_id: string

- event_time: datetime

- event_type: "signup", "renewal", "cancel"

- plan_price: float

Business rules:

1. An "active user" is someone who has at least one "signup" or "renewal"

event in the last 90 days and has NOT had a "cancel" event after that.

2. For active users, I want their 90‑day revenue:

sum of plan_price for "signup" and "renewal" in the last 90 days.

3. I need:

- total_active_users

- total_90d_revenue

- ARPU_90d = total_90d_revenue / total_active_users (2 decimals)

Write Pandas code that:

- Implements those rules step by step.

- Prints a summary line:

"Active users: X, 90‑day revenue: Y, 90‑day ARPU: Z".

Add inline comments explaining each step.

Without those rules, the model might invent a default definition of “active” that doesn’t match your business. And then all your dashboards lie.

Principle 4: Break scary problems into boring steps

“Do everything in one line” is a flex for conference talks, not for GPT‑5 prompts.

For anything involving multiple tables, custom rules, or time windows, give the model a recipe:

There are two DataFrames:

orders_df:

- order_id (string)

- user_id (string)

- ordered_at (datetime)

- sku (string)

- quantity (int)

- unit_price (float)

users_df:

- user_id (string)

- tier (string: "free", "plus", "pro")

- joined_at (datetime)

Goal: For Q1 2025, compute per tier:

- total_revenue

- order_count

- avg_order_value = total_revenue / order_count (2 decimals)

Steps to follow:

1. In orders_df, add total_price = quantity * unit_price.

2. Filter orders_df to Q1 2025 (2025‑01‑01 to 2025‑03‑31).

3. Inner join with users_df on user_id, keeping all columns.

4. Group by tier and compute:

- total_revenue = sum(total_price)

- order_count = number of orders

5. Compute avg_order_value.

6. Sort by total_revenue descending.

7. Save as ./reports/q1_2025_tier_revenue.csv.

Write Pandas code that follows these steps and adds comments.

You’re basically giving GPT‑5 a mini‑design doc. It rewards you with code that mirrors your mental model, which makes reviewing and debugging much easier.

Principle 5: For debugging, show code + traceback

If you just paste the error message, the model has to guess the context. If you paste the code without the error, it has to guess what went wrong.

Paste both.

Example prompt:

I'm getting an error when running this Pandas code.

Code:

-----------------

import pandas as pd

events_df = pd.read_csv("./data/events.csv")

events_df["event_time"] = pd.to_datetime(events_df["event_time"])

active = events_df[

(events_df["status"] == "active") &

(events_df["event_time"] >= "2024-01-01")

]

daily = active.groupby("event_date")["user_id"].nunique()

-----------------

Error:

-----------------

KeyError: 'event_date'

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "analysis.py", line 12, in <module>

daily = active.groupby("event_date")["user_id"].nunique()

...

-----------------

Please:

1. Explain the real root cause.

2. Show the fixed code.

3. Suggest a quick check to prevent this class of bug.

GPT‑5 can now:

- see that

event_datedoesn’t exist (probably you meantevent_time.dt.date), - patch the logic,

- and give you defensive patterns (“assert 'event_date' in active.columns before groupby”).

4. Case studies: real‑world Pandas + GPT‑5 workflows

Let’s walk through five scenarios you’ll actually hit at work.

Case 1: “Please clean this horrible CSV for me”

Background

You get a messy ecommerce dataset at ./data/raw_orders.csv with:

- mixed date formats,

- missing user IDs,

- NaN and insane values in the amount column.

You could write the cleaning pipeline by hand… or you can spec it and let GPT‑5 draft it.

Prompt sketch

I have a CSV at ./data/raw_orders.csv with columns:

- order_id: string, no missing values

- ordered_at: string, dates like "2024/5/1" and "2024-05-01"

- buyer_id: string, about 5% are NaN

- gross_amount: float, has NaN, negatives, and outliers > 200000

- pay_method: string, values "wechat", "alipay", "unionpay"

Write Pandas code to:

1. Read the CSV and print head(), info(), and describe().

2. Convert ordered_at to datetime, normalised to "YYYY-MM-DD".

3. Fill missing buyer_id with "UNKNOWN".

4. For gross_amount:

a. Fill NaN with the column median (2 decimals).

b. Drop rows where gross_amount < 0 or > 200000.

5. Print info() and describe() after cleaning.

6. Save cleaned data to ./data/clean_orders.csv without index.

Add clear comments and keep all thresholds dynamic (no hard‑coded median).

Typical GPT‑5 output (simplified & slightly tweaked)

import pandas as pd

# 1. Load and inspect raw data

orders_df = pd.read_csv("./data/raw_orders.csv")

print("=== Raw head ===")

print(orders_df.head())

print("\n=== Raw info ===")

print(orders_df.info())

print("\n=== Raw describe (numeric) ===")

print(orders_df.describe())

# 2. Normalise ordered_at to datetime

orders_df["ordered_at"] = pd.to_datetime(

orders_df["ordered_at"],

errors="coerce" # anything weird becomes NaT

)

# Optional: keep as datetime or normalise to string

orders_df["ordered_date"] = orders_df["ordered_at"].dt.strftime("%Y-%m-%d")

# 3. Fill missing buyer IDs

orders_df["buyer_id"] = orders_df["buyer_id"].fillna("UNKNOWN")

# 4. Handle gross_amount

# 4a. Compute median dynamically

median_amount = orders_df["gross_amount"].median()

orders_df["gross_amount"] = orders_df["gross_amount"].fillna(median_amount)

# 4b. Remove extreme values

mask_valid = (orders_df["gross_amount"] >= 0) & (orders_df["gross_amount"] <= 200000)

clean_df = orders_df.loc[mask_valid].copy()

print(f"\nDropped {len(orders_df) - len(clean_df)} rows with extreme gross_amount")

# 5. Inspect cleaned data

print("\n=== Cleaned info ===")

print(clean_df.info())

print("\n=== Cleaned describe ===")

print(clean_df.describe())

# 6. Save

clean_df.to_csv("./data/clean_orders.csv", index=False)

print("\nSaved cleaned data to ./data/clean_orders.csv")

You then run it, eyeball the summary prints, and adjust thresholds if needed. The heavy lifting (and boilerplate) came “for free”.

Case 2: “My script works but takes 10 minutes on 5M rows”

Background

You have a 5‑million‑row log table logs_df and some classic iterrows() spaghetti to count daily visits per user. It’s painfully slow.

Slow code

import time

logs_df["event_date"] = logs_df["logged_at"].dt.date

visit_counts = {}

start = time.time()

for _, row in logs_df.iterrows():

if row["event_type"] != "view":

continue

key = (row["user_id"], row["event_date"])

visit_counts[key] = visit_counts.get(key, 0) + 1

result = (

pd.DataFrame(

[(u, d, c) for (u, d), c in visit_counts.items()],

columns=["user_id", "event_date", "visit_count"]

)

)

print(f"Loop time: {time.time() - start:.2f}s")

Prompt sketch

I have a DataFrame logs_df with 5M rows:

- user_id: string (~1M uniques)

- logged_at: datetime

- event_type: string, values include "view", "click", "purchase"

The code below works but uses iterrows() and a Python dict; it takes ~600s.

[PASTE CODE]

Please:

1. Explain why this is slow in Pandas terms.

2. Rewrite it using vectorised operations and groupby.

3. Keep the same output columns.

4. Roughly estimate run time on 5M rows.

5. Suggest 2–3 general optimisation tips for big Pandas jobs.

Optimised pattern GPT‑5 will usually give

import time

start = time.time()

# Filter only "view" events

views_df = logs_df[logs_df["event_type"] == "view"].copy()

# Extract date once, no loop

views_df["event_date"] = views_df["logged_at"].dt.date

# Group and count

result = (

views_df

.groupby(["user_id", "event_date"])

.size()

.reset_index(name="visit_count")

)

print(f"Vectorised time: {time.time() - start:.2f}s")

Performance difference? On typical hardware, this is the difference between “go get a coffee” and “don’t bother blinking”.

Case 3: “Product asks for a fuzzy metric, we need an actual query”

Background

PM says: “Can we get ‘category repeat rate’ for Jan–Apr? If a user buys the same category again within 30 days, that counts as a repeat.”

That’s not a query. It’s a story. Your job is to turn it into steps, then code.

Prompt sketch

We have two DataFrames:

orders_df:

- order_id: string

- user_id: string

- ordered_at: datetime

- product_id: string

- qty: int

products_df:

- product_id: string

- category: string, e.g. "Electronics", "Clothing"

Business request:

"Jan–Apr 2024 category repeat rate":

- For each category, consider users who bought that category in that period.

- A user is a "repeat user" for a category if they have at least two purchases

in that category within any rolling 30‑day window.

- First purchase doesn't count as repeat; second (within 30 days) and later do.

Please:

1. Translate this into clear Pandas steps, numbered.

2. Implement those steps in code.

3. Output a DataFrame with columns:

category, unique_buyers, repeat_buyers, repeat_rate

where repeat_rate = repeat_buyers / unique_buyers (4 decimals),

sorted by repeat_rate desc.

4. Add comments explaining each step.

Core logic GPT‑5 tends to use (simplified)

# 1. Attach categories

merged = orders_df.merge(products_df, on="product_id", how="inner")

# 2. Filter Jan–Apr 2024

mask = (merged["ordered_at"] >= "2024-01-01") & (merged["ordered_at"] < "2024-05-01")

period_df = merged.loc[mask].copy()

# 3. Sort by user, category, date

period_df = period_df.sort_values(["user_id", "category", "ordered_at"])

# 4. For each user+category, compute time diff between consecutive orders

grouped = period_df.groupby(["user_id", "category"], group_keys=False)

def mark_repeat(group):

group = group.copy()

group["delta_days"] = group["ordered_at"].diff().dt.days

group["is_repeat"] = group["delta_days"].le(30) # 2nd+ within 30 days

return group

labeled = grouped.apply(mark_repeat)

# 5. Collapse to user+category granularity

user_cat = (

labeled

.groupby(["category", "user_id"])

.agg(has_repeat=("is_repeat", "any"))

.reset_index()

)

# 6. Category‑level metrics

metrics = (

user_cat

.groupby("category")

.agg(

unique_buyers=("user_id", "nunique"),

repeat_buyers=("has_repeat", "sum")

)

.reset_index()

)

metrics["repeat_rate"] = (metrics["repeat_buyers"] / metrics["unique_buyers"]).round(4)

metrics = metrics.sort_values("repeat_rate", ascending=False)

This is exactly the kind of thing you could write by hand… but it’s much nicer to have GPT‑5 write the first draft while you double‑check the business definition.

Case 4: “Why does this merge explode with dtype errors?”

Background

You try to merge a user table and an orders table, and Pandas screams:

ValueError: Cannot merge on int64 and object columns.

Prompt sketch

I get a dtype merge error.

Context:

- users_df has user_id as int64

- orders_df has user_id as object (string)

Code and dtypes:

[PASTE dtypes and merge code and full traceback]

Please:

1. Explain the specific cause of the error.

2. Show two different correct ways to fix it:

- one where user_id becomes string,

- one where it becomes int.

3. Mention when each approach is appropriate.

4. Show a small assert or check to run before merging.

GPT‑5 will usually:

- point out the dtype mismatch,

- recommend

astype(str)vsastype(int)depending on your data, - add something like:

assert users_df["user_id"].dtype == orders_df["user_id"].dtype

before merging, which is a nice habit to keep.

Case 5: “I’m sick of manual monthly reports”

Background

Every month you get sales_2024MM.csv and you need to:

- compute a couple of metrics per region,

- format 12 sheets in Excel,

- send them out.

This is a perfect “prompt → automation” flow.

Prompt sketch

I need a Pandas + openpyxl script.

Data:

- Monthly CSVs: ./data/sales_2024MM.csv for MM in 01..06.

- Columns: order_id, user_id, region, amount, order_date.

Regions of interest: ["London", "Manchester", "Birmingham", ...] (12 total).

For each month:

1. Read the CSV. If file is missing, log a warning and skip.

2. Filter to the 12 regions.

3. For each region compute:

- total_amount: sum(amount), 2 decimals.

- order_count: nunique(order_id).

- avg_order: total_amount / order_count, 2 decimals.

4. Create an Excel file ./reports/monthly_2024MM.xlsx

with one sheet per region, sheet name = region.

5. Each sheet should have:

- A title row like "2024‑MM REGION Sales Report".

- A table with columns: Region, Total (£), Orders, AOV (£).

Add basic error handling and print how many months succeeded vs failed.

You’ll get back something very close to production code. You might tweak:

- the list of regions,

- the folder names,

- some formatting – but the skeleton is done.

5. Pandas + GPT‑5 FAQ: why is my generated code weird?

A few patterns I see constantly:

|

Symptom |

Likely cause |

Fix in your prompt |

|---|---|---|

|

Column names don’t match your data |

You never told the model the real column names |

List them explicitly; optionally include 1–2 example rows. |

|

Code doesn’t scale to big data |

You didn’t say “5M rows, 10 columns” or ask for optimisation |

Mention data size; ask for vectorised / groupby solution and no |

|

The business metric is subtly wrong |

You used terms like “active” or “churn” without defining them |

Define metrics with formulas, time windows, and edge cases. |

|

It uses deprecated Pandas APIs (like |

Training data may be on older versions |

Tell it “assume Pandas 2.x, avoid DataFrame.append, prefer concat”. |

|

Output looks right but is overly verbose |

You over‑specified every micro‑step |

After first draft, ask: “Now simplify this, merging redundant steps, same behaviour.” |

|

Code is uncommented and opaque |

You never asked for comments |

Explicitly require comments or even “explain line by line after the code”. |

Treat this as an iterative loop:

- Prompt → code.

- Run → see where it hurts.

- Paste back errors, sample outputs, or pain points.

- Refine the prompt and regenerate.

GPT‑5 is surprisingly good at refactoring its own code when you say “now optimise that” or “make this more readable”.

6. Two practice prompts

Exercise 1: Behaviour filter + hot products

Goal

From a user behaviour log, find products with at least 10 purchases during the first week of May 2024.

Prompt

I have a CSV at ./data/user_behavior.csv with columns:

- user_id: string

- behavior_time: string, e.g. "2024-05-01 09:30:00"

- behavior_type: string: "view", "favorite", "add_to_cart", "purchase"

- product_id: string

Write Pandas code to:

1. Read the CSV, parsing behavior_time to datetime.

2. Filter rows where:

- behavior_type == "purchase"

- behavior_time between 2024-05-01 00:00:00 (inclusive)

and 2024-05-07 23:59:59 (inclusive).

3. Group by product_id and compute purchase_count (# of rows).

4. Keep products with purchase_count >= 10.

5. Sort by purchase_count descending.

6. Save results to ./output/hot_products_20240501_0707.csv without index.

Include comments and one or two sanity checks

(e.g. min/max timestamp of the filtered frame).

Exercise 2: Optimise “last purchase per user”

You have this slow code for 1M rows:

import pandas as pd

import time

df = pd.read_csv("./data/user_purchases.csv")

df["purchase_time"] = pd.to_datetime(df["purchase_time"])

start = time.time()

last_purchase = {}

for _, row in df.iterrows():

uid = row["user_id"]

ts = row["purchase_time"]

if uid not in last_purchase or ts > last_purchase[uid]:

last_purchase[uid] = ts

result = pd.DataFrame(

list(last_purchase.items()),

columns=["user_id", "last_purchase_time"]

)

print(f"Elapsed: {time.time() - start:.2f}s")

Prompt

This code computes each user's last purchase time using iterrows()

and a dict. It works on 1M rows but takes ~30 seconds.

[PASTE CODE]

Please:

1. Explain why iterrows() + Python dict is slow here.

2. Rewrite it using Pandas groupby or similar

in a fully vectorised way, preserving the output schema.

3. Estimate the typical runtime for 1M rows on a laptop.

4. Briefly explain why the new version is faster in terms of:

- Python vs C‑level loops

- memory access patterns.

GPT‑5 will typically give you:

result = (

df.groupby("user_id", as_index=False)["purchase_time"]

.max()

.rename(columns={"purchase_time": "last_purchase_time"})

)

…plus a perfectly reasonable micro‑lecture on vectorisation and C‑backed loops.

7. Putting it all together

Prompt + Pandas is not about replacing you with an LLM. It’s about moving your effort:

- less time remembering whether it’s

reset_index()orreset_index(drop=True), - more time arguing about how to define “power user” or “repeat purchase” in a way that actually matters.

If you give GPT‑5:

- Concrete data descriptions (columns, types, paths),

- Precise goals and output formats,

- Explicit business rules,

- Step‑by‑step breakdowns for complex flows, and

- Full code + error messages when things go boom,

…you end up with a workflow where:

Business asks → you design prompt → GPT‑5 drafts Pandas → you sanity‑check and ship.

No more twelve‑tab Stack Overflow journeys for every .groupby().

Next time you open a notebook and think “ugh, this is going to be annoying”, try writing a prompt first. Pandas will still be Pandas, but you won’t have to wrestle it alone.