Table of Links

2 INTERACTIVE WORLD SIMULATION

3.1 DATA COLLECTION VIA AGENT PLAY

3.2 TRAINING THE GENERATIVE DIFFUSION MODEL

4.1 AGENT TRAINING

4.2 GENERATIVE MODEL TRAINING

5.1 SIMULATION QUALITY

5.2 ABLATIONS

7 DISCUSSION, ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND REFERENCES

5 RESULTS

5.1 SIMULATION QUALITY

Overall, our method achieves a simulation quality comparable to the original game over long trajectories in terms of image quality. For short trajectories, human raters are only slightly better than random chance at distinguishing between clips of the simulation and the actual game. Image Quality. We measure LPIPS (Zhang et al., 2018) and PSNR using the teacher-forcing setup described in Section 2, where we sample an initial state and predict a single frame based on a trajectory of ground-truth past observations. When evaluated over a random holdout of 2048 trajectories taken in 5 different levels, our model achieves a PSNR of 29.43 and an LPIPS of 0.249. The PSNR value is similar to lossy JPEG compression with quality settings of 20-30 (Petric & Milinkovic, 2018). Figure 5 shows examples of model predictions and the corresponding ground truth samples.

Video Quality. We use the auto-regressive setup described in Section 2, where we iteratively sample frames following the sequences of actions defined by the ground-truth trajectory, while conditioning the model on its own past predictions. When sampled auto-regressively, the predicted and groundtruth trajectories often diverge after a few steps, mostly due to the accumulation of small amounts of different movement velocities between frames in each trajectory. For that reason, per-frame PSNR and LPIPS values gradually decrease and increase respectively, as can be seen in Figure 6. The predicted trajectory is still similar to the actual game in terms of content and image quality, but per-frame metrics are limited in their ability to capture this (see Appendix A.1 for samples of autoregressively generated trajectories).

We therefore measure the FVD (Unterthiner et al., 2019) computed over a random holdout of 512 trajectories, measuring the distance between the predicted and ground truth trajectory distributions, for simulations of length 16 frames (0.8 seconds) and 32 frames (1.6 seconds). For 16 frames our model obtains an FVD of 114.02. For 32 frames our model obtains an FVD of 186.23.

Human Evaluation. As another measurement of simulation quality, we provided 10 human raters with 130 random short clips (of lengths 1.6 seconds and 3.2 seconds) of our simulation side by side with the real game. The raters were tasked with recognizing the real game (see Figure 14 in Appendix A.6). The raters only choose the actual game over the simulation in 58% or 60% of the time (for the 1.6 seconds and 3.2 seconds clips, respectively).

5.2 ABLATIONS

To evaluate the importance of the different components of our methods, we sample trajectories from the evaluation dataset and compute LPIPS and PSNR metrics between the ground truth and the predicted frames.

5.2.1 CONTEXT LENGTH

We evaluate the impact of changing the number N of past observations in the conditioning context by training models with N ∈ {1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64} (recall that our method uses N = 64). This affects both the number of historical frames and actions. We train the models for 200,000 steps keeping the decoder frozen and evaluate on test-set trajectories from 5 levels. See the results in Table 1. As expected, we observe that generation quality improves with the length of the context. Interestingly, we observe that while the improvement is large at first (e.g. between 1 and 2 frames), we quickly approach an asymptote and further increasing the context size provides only small improvements in quality. This is somewhat surprising as even with our maximal context length, the model only has access to a little over 3 seconds of history. Notably, we observe that much of the game state is persisted for much longer periods (see Section 7). While the length of the conditioning context is an important limitation, Table 1 hints that we’d likely need to change the architecture of our model to efficiently support longer contexts, and employ better selection of the past frames to condition on, which we leave for future work.

5.2.2 NOISE AUGMENTATION

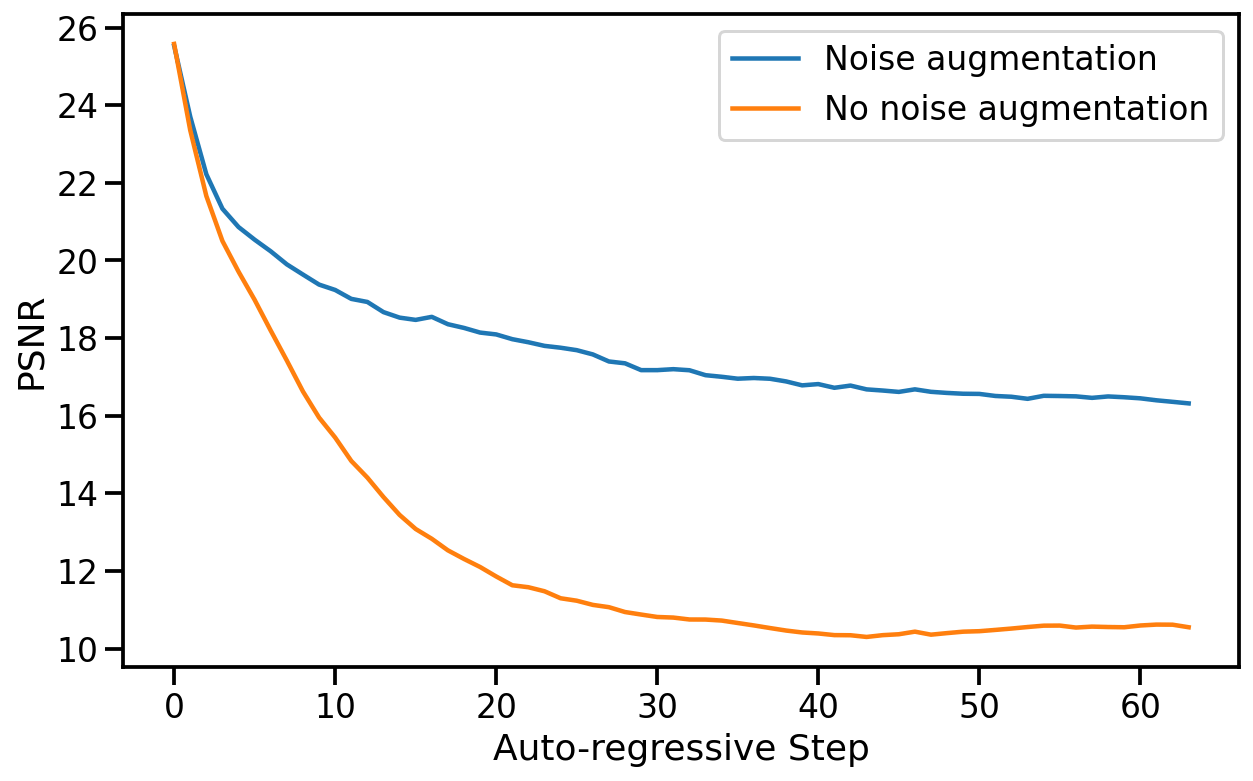

To ablate the impact of noise augmentation we train a model without added noise. We evaluate both our standard model with noise augmentation and the model without added noise (after 200k training steps) auto-regressively and compute PSNR and LPIPS metrics between the predicted frames and the ground-truth over a random holdout of 512 trajectories. We report average metric values for each auto-regressive step up to a total of 64 frames in Figure 7.

Without noise augmentation, LPIPS distance from the ground truth increases rapidly compared to our standard noise-augmented model, while PSNR drops, indicating a divergence of the simulation from ground truth.

5.2.3 AGENT PLAY

We compare training on agent-generated data to training on data generated using a random policy. For the random policy, we sample actions following a uniform categorical distribution that doesn’t depend on the observations. We compare the random and agent datasets by training 2 models for 700k steps along with their decoder. The models are evaluated on a dataset of 2048 human-play trajectories from 5 levels. We compare the first frame of generation, conditioned on a history context of 64 ground-truth frames, as well as a frame after 3 seconds of auto-regressive generation. Overall, we observe that training the model on random trajectories works surprisingly well, but is limited by the exploration ability of the random policy. When comparing the single frame generation the agent works only slightly better, achieving a PNSR of 25.06 vs 24.42 for the random policy. When comparing a frame after 3 seconds of auto-regressive generation, the difference increases to 19.02 vs 16.84. When playing with the model manually, we observe that some areas are very easy for both, some areas are very hard for both, and in some the agent performs much better. With that, we manually split 456 examples into 3 buckets: easy, medium, and hard, manually, based on their distance from the starting position in the game. We observe that on the easy and hard sets, the agent performs only slightly better than random, while on the medium set the difference is much larger in favor of the agent as expected (see Table 2). See Figure 13 in Appendix A.5 for an example of the scores during a single session of human play.

This paper is