A designer friend recently told me she spent three days trying to figure out why her company's checkout flow made users confirm their email address twice. It seemed obviously redundant—just bad UX someone forgot to clean up. She asked the PM. She asked the engineer who built it. She even dug through old PRs looking for context.

The best answer she got was: "There was something with the vendor API, but I don't remember the details. Maybe check with Sarah?"

Sarah left the company five months ago.

Eventually, she found a Slack thread from 18 months earlier where someone mentioned the vendor's email validation was broken and that they'd had incidents with typos causing lost orders. The double confirmation was catching 90% of errors. Not elegant, but solving a real problem.

She almost removed it because no one had told her why it existed.

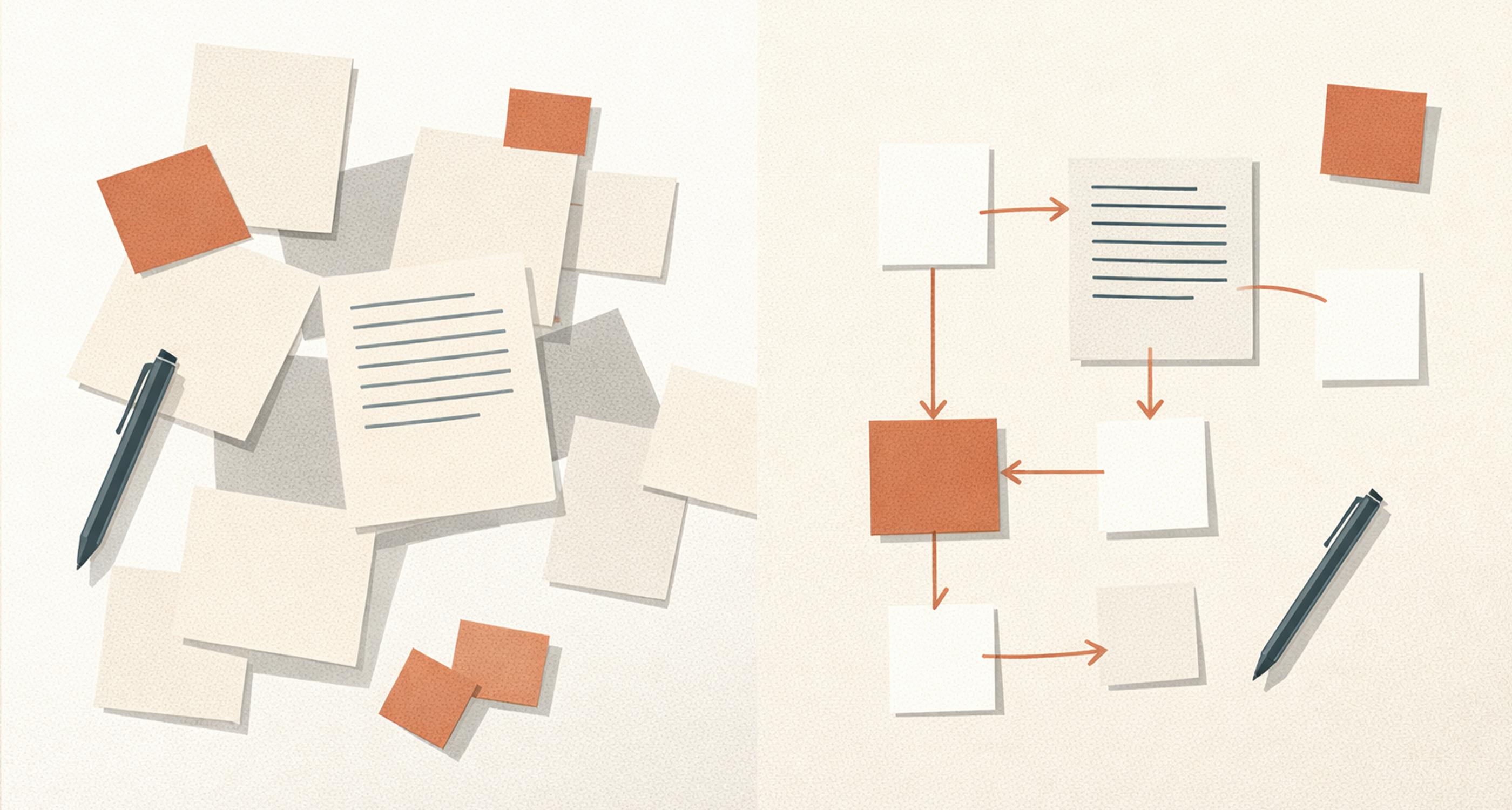

This keeps happening. Someone makes a thoughtful decision based on real constraints. Six months later, the constraints are invisible, and the decision looks arbitrary. A new designer shows up, sees something that seems obviously wrong, and "fixes" it—only to rediscover why it was that way in the first place.

We're really good at documenting what we build

Design teams are pretty rigorous about certain kinds of documentation. We have detailed component specs. We maintain Figma libraries. We write interaction patterns and accessibility guidelines. Some teams even have comprehensive design systems with usage examples and do's and don'ts.

All of that tells you what to build and how to build it.

None of it tells you why things are the way they are.

Why is the button that specific height? Why did we choose this navigation pattern over the other one that tested well? Why does this flow have an extra step that seems unnecessary?

The specs and guidelines don't answer these questions because they're not designed to. They're maintenance documentation—they help you stay consistent with existing decisions. But they don't explain how we got to those decisions in the first place.

The knowledge that actually matters

When I'm trying to understand an unfamiliar part of the product, here's what I'm really trying to figure out:

What problem were you actually solving? Not the high-level product goal, but the specific issue that made you design it this particular way.

What did you try that didn't work? If I'm about to propose a solution, I want to know if someone already tried it and hit a wall I can't see yet.

What constraints were you working with? Technical limitations, time pressure, vendor restrictions, organizational dynamics. The context that made this the right answer then, even if it might not be the right answer now.

What were you assuming? Every design bakes in assumptions about users, technology, business priorities. If those assumptions changed, the design should probably change too. But I need to know what they were first.

What did you intentionally leave unfinished? There's a difference between "we didn't get to this" and "this is working as intended." If I don't know which is which, I waste time optimizing things that are actually fine.

This is the information that prevents me from rediscovering what you already know.

Why this doesn't exist

I understand why we don't document this stuff. You've just finished designing and shipping something—you're tired, and now someone's asking you to write more? Your next project is already starting. Nobody's performance review mentions documentation quality.

Also, documenting your reasoning kind of feels like admitting your design might not be perfect. Like you're pre-writing the explanation for why future people shouldn't trust your judgment.

But that's backwards. Good documentation assumes future people are smart and will rightfully question your choices. You're just giving them enough information to question intelligently instead of blindly.

And honestly, the person who benefits most from this documentation is often you, three months later, when someone asks why you designed something a certain way and you can't quite remember.

What I've started doing

The best documentation practice I've found is almost embarrassingly simple: write down your decisions.

Not specs. Not detailed rationale. Just a short record of what you decided and why.

In my team, we started keeping these in a shared folder—just markdown files with names like "2024-01-why-we-redesigned-payment-summary.md"

The format is deliberately minimal:

Decision: What we built

Problem: What we were trying to solve

Options we considered:

Option A - why we didn't choose it

Option B - why we didn't choose it

Option C (what we built) - why we chose it

Tradeoffs: What we're accepting by choosing this

Date and people: When we decided and who to ask for more context

That's it. Usually takes me 10-15 minutes to write. But when someone asks about it six months later, that document is worth hours of archaeology.

When I actually bother writing these

I don't write a decision record for every design choice—that would be absurd. I write them when:

- I'm making a decision I can already imagine someone questioning me later

- Multiple reasonable options existed and it wasn't obvious which to choose

- We're working around a constraint that isn't visible in the final design

- The solution seems counterintuitive but there's a good reason for it

- I spent significant time exploring alternatives that failed

Basically: if someone's going to look at this in six months and wonder "why did they do it that way?", I document it now while I still remember.

The research problem is worse

User research suffers from this even more. Teams conduct research, learn important things, make decisions based on those learnings, and then... the insights evaporate.

The deck lives in some Google Drive folder organized by quarter. Six months later, someone proposes a feature. It seems great. They build it. It fails for exactly the reason your research predicted it would.

"Oh yeah, we learned that in research."

Okay, where's the research?

"Um... I think it was Q2? Or maybe Q3? Let me check if I still have access to that folder..."

One team I worked with started maintaining a simple research insights database. Not the full reports—those still live in folders somewhere. Just a searchable list of key learnings organized by product area.

So when someone asks "should we add social login?", you can quickly find "we researched that in March 2023, here's what we learned, here's the deck if you want details."

It's not comprehensive. It's not perfect. But it's so much better than nothing.

Figma files are terrible historical records

Looking at an old Figma file tells you what shipped. It doesn't tell you the thirty variations you tried first, or why each one didn't work, or what technical constraint ruled out the obviously better solution.

Some designers leave their exploration frames visible with notes explaining what didn't work. That's better than nothing, but it still relies on you remembering to document while you're in the messy middle of the process.

I've found it's easier to document after I've landed on a solution, when I actually know what was important enough to write down.

What changes as you get more senior

When I look at work from designers at different levels, the visible output isn't that different. The gap is in what they leave behind for the next person.

More experienced designers document their reasoning. Not because they're more organized or have more time, but because they've been the person six months later enough times to know how valuable that context is.

They've learned that "I'll remember why I did this" is a lie you tell yourself. You won't remember, and neither will anyone else. Write it down now or lose it forever.

The real cost

The longer someone's been on a team, the more knowledge they carry that isn't written anywhere. They know why the navigation is structured this way. They know what user feedback shaped that particular flow. They know which previous attempts failed and why.

When they leave, all that context leaves with them.

I've joined teams where this happened. The Figma files are there. The shipped product is there. But nobody can explain why certain decisions were made. So you either accept them as mysterious constraints or you change them and hope you don't break something important.

Either way, you're guessing. And that's expensive.

Something you could try

Next time you make a design decision that wasn't obvious, take ten minutes to write down what you decided and why. Include what else you considered. Note any constraints or assumptions that shaped your thinking.

Put it somewhere the next designer can find it. Not in your head. Not in Slack. Somewhere that persists.

You probably won't think it matters. But the next person—or you, six months from now—will be incredibly grateful it exists.

What I'm still figuring out

I'm not claiming I have this solved. I still forget to document things. I still underestimate what future-me will want to know. I still debate whether something is worth writing down.

But I've learned that when I'm unsure if something is worth documenting, it probably is. The things that feel obvious now are exactly the things that won't feel obvious later.

The documentation nobody asks for is usually the documentation everyone eventually wishes existed.

What if you didn't have to remember to document?

I've been thinking about this differently lately. What if the problem isn't that we're bad at documenting? What if we're asking people to document at exactly the wrong time?

You just shipped something. You're exhausted. Your next project is already starting. And now someone's supposed to sit down and write about decisions they made three weeks ago? Of course, that doesn't happen.

So here's what keeps bouncing around in my head: What if you didn't have to remember to document?

Imagine you're in Figma trying five different navigation patterns. You're in Slack, explaining to your PM why Option C won't work due to the vendor API or lack of a dev component. You finally land on Option D and ship it.

Right after you ship, you get a small notification: "I noticed you explored several navigation approaches and mentioned vendor constraints. Want to save the context?" Click it, and there's already a draft decision record. It's pulled from your Slack discussion, your Figma iterations, and those design review meetings where you explained the tradeoffs.

You spend 90 seconds reviewing it, maybe adding one detail the AI missed, and save it.

Six months later, a new designer is looking at that navigation and wondering why it's structured this way. Instead of an archaeology deep-dive, they type "why is navigation structured this way" and immediately see: "Navigation redesigned June 2024. The Vendor API couldn't support nested menus, so we explored 5 alternatives. This was the only one that met both technical constraints and usability needs. Full context here."

No one had to remember to document. The context was captured during the natural workflow, structured when you had time, and surfaced exactly when someone needed it.

The Final Framing

I don't know if this exact thing exists or if someone should build it. But I know this: the current answer of "just write better documentation" isn't working because it runs counter to human nature.

Maybe the real solution isn't better discipline. Maybe it's building systems that work with our natural behavior instead of against it.

Or maybe you've figured out something better. I'd love to know what's working for your team.