This is a Plain English Papers summary of a research paper called EcoNet: Multiagent Planning and Control Of Household Energy Resources Using Active Inference. If you like these kinds of analysis, join AIModels.fyi or follow us on Twitter.

The problem households can't solve alone

Your home faces an impossible puzzle. You want lower energy bills. You want fewer emissions. You want comfortable temperatures. These goals should coexist peacefully, but they don't. Heating that spare room burns cash and carbon. Deferring that heat until cheaper hours sacrifices comfort. Minimizing emissions might mean using less efficient appliances at peak times. The contradictions compound when you add uncertainty: you don't know tomorrow's weather, solar generation, or electricity prices. Traditional approaches force you to choose one priority and lock it in, yet what matters to you changes hour by hour.

This is where most household energy management systems fail. They optimize for a single goal or enforce a rigid hierarchy of goals. A thermostat maintains temperature. A smart charger minimizes cost. A solar manager maximizes self-consumption. Each device follows its checklist independently, and the overall system lurches between conflicting demands.

EcoNet proposes something different. Instead of stacking rigid optimizations on top of each other, the system treats energy management as an act of collective reasoning, where devices share probabilistic beliefs about the world and coordinate their actions naturally. The core insight is that this mirrors how brains actually work: you don't precommit to an optimal life plan and then execute it. You maintain evolving beliefs about the world, observe what happens, update those beliefs, and choose actions that move toward your goals given what you currently know. This framework, called active inference, translates directly to household energy management.

Why traditional approaches break

A conventional thermostat operates like a worker following instructions: "If room temperature drops below 68 degrees, turn on heat. If it rises above 72 degrees, turn on cooling." This binary thinking works fine for a single objective. But real households have multiple objectives, and they conflict.

Suppose you add a cost constraint: "Don't heat during peak-price hours." Now the checklist explodes. Should comfort override cost? By how much? For how long? The system can't answer these questions because answering them requires reasoning about tradeoffs under uncertainty. What if you defer heating for an hour to save money, but the weather changes and you end up uncomfortable anyway? How much discomfort is worth how much savings?

Traditional optimization forces you to answer these questions upfront, before you see the data. You must precommit to weights: "comfort is worth $5 per degree-hour of deviation, emissions are worth $0.02 per kilogram CO2." These numbers are guesses. They're wrong. And they don't adapt when circumstances change. A household that prioritizes emissions reduction on a wind-heavy day should prioritize cost on a day when solar costs are undercut by coal. The priorities should flow from the current state of the world, not a locked-in configuration.

This is the structural failure of conventional approaches. They ask: "What's the optimal schedule?" But that's the wrong question. The right question is: "Given current uncertainty about the future, what should we believe, and what actions follow naturally from those beliefs?"

Thinking like a brain instead of a computer

Active inference formalizes how brains navigate the world. You don't pre-plan every action based on a rigid hierarchy. Instead, you maintain beliefs: "The kettle boils in three minutes, usually." You observe what happens: "It's boiling faster than usual because the burner is hotter." You update your beliefs. You choose actions that align with your goals given those updated beliefs. When you're cold and want warmth, you put on a sweater. When you realize the sweater is in the wash, your beliefs update, and your actions adjust naturally.

The mathematics of active inference formalize this process. Rather than asking "What's optimal?", it asks "What should I believe about the world, and what actions reduce the gap between current conditions and desired outcomes, given those beliefs?" For energy management, this shift is powerful.

Instead of a thermostat that simply knows "room is 70 degrees," EcoNet maintains a thermostat agent that represents its knowledge probabilistically: "The room is probably 70 degrees, but I'm uncertain because I haven't checked in ten minutes, the front door just opened, and heating is running." When new observations arrive, the agent updates its beliefs using Bayesian reasoning: temperature sensor reading, occupancy activation, time of day. Each observation refines the distribution of possibilities.

This isn't machine learning in the flashy sense. It's systematic belief refinement through observation. It's also interpretable. You can inspect the system's beliefs and understand why it made a choice, rather than staring into a neural network's black box.

How EcoNet learns a model of the world

Imagine learning the electricity grid's emissions patterns. For the first few days, you have no idea when power is dirtiest. After observing a week, you notice that peak emissions tend to happen between 5 and 9 PM. This belief isn't certain, but it guides choices. Defer consumption to off-peak hours when you can.

EcoNet does this continuously and formally. Early in its operation, when the system doesn't yet know how room temperature responds to heating actions, it must plan with deep uncertainty. If you turn on the thermostat, how much will the room warm? How fast? How long will that warmth persist? This uncertainty matters because poor predictions lead to poor decisions.

As days pass and the system observes what actually happens after its actions, that uncertainty shrinks. The system learns the thermal dynamics of the house. It learns the grid's emissions curve. It learns solar generation patterns. With better beliefs, its decisions improve.

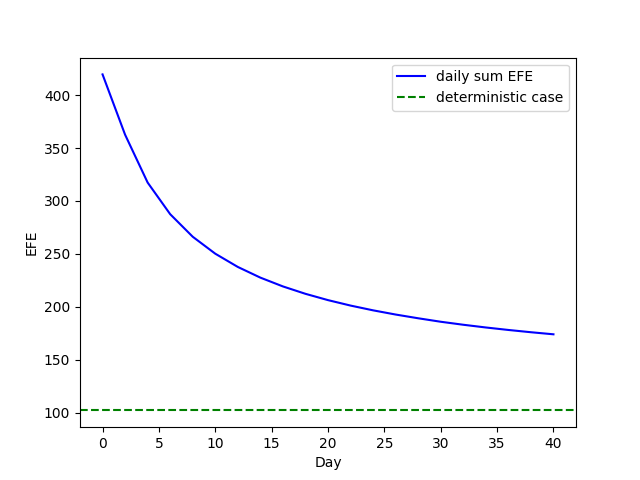

Figure 9 quantifies this improvement. The left panel shows negative expected free energy, a measure of decision quality, dropping steadily over 40 days of operation. After 40 days, the agent's ability to achieve target room temperature reaches the level of a hand-coded deterministic model. The system learns as effectively as an engineer with a blueprint.

Agent beliefs about battery state of charge (top) and beliefs about ToU rates (bottom, shaded).

Agent beliefs about battery state of charge (top) and beliefs about ToU rates (bottom, shaded).

The learning extends across all domains the system manages. Look at the battery beliefs shown in Figure 5. The shaded regions represent uncertainty about time-of-use rates. As the system observes the rate schedule over days, the uncertainty tightens. The bands converge to the true pattern. The same learning happens for solar generation, baseline energy use, and the relationship between thermostat actions and room temperature.

When circumstances change, the system adapts. If the utility alters the time-of-use schedule, the previous beliefs become less predictive. New observations arrive that contradict old patterns. The system detects this divergence and updates its beliefs to match the new reality. Figure 6 illustrates this: when an evening high-ToU period lengthens from two hours to three hours, the agent's beliefs shift and its policies adjust accordingly.

Devices that share understanding instead of following orders

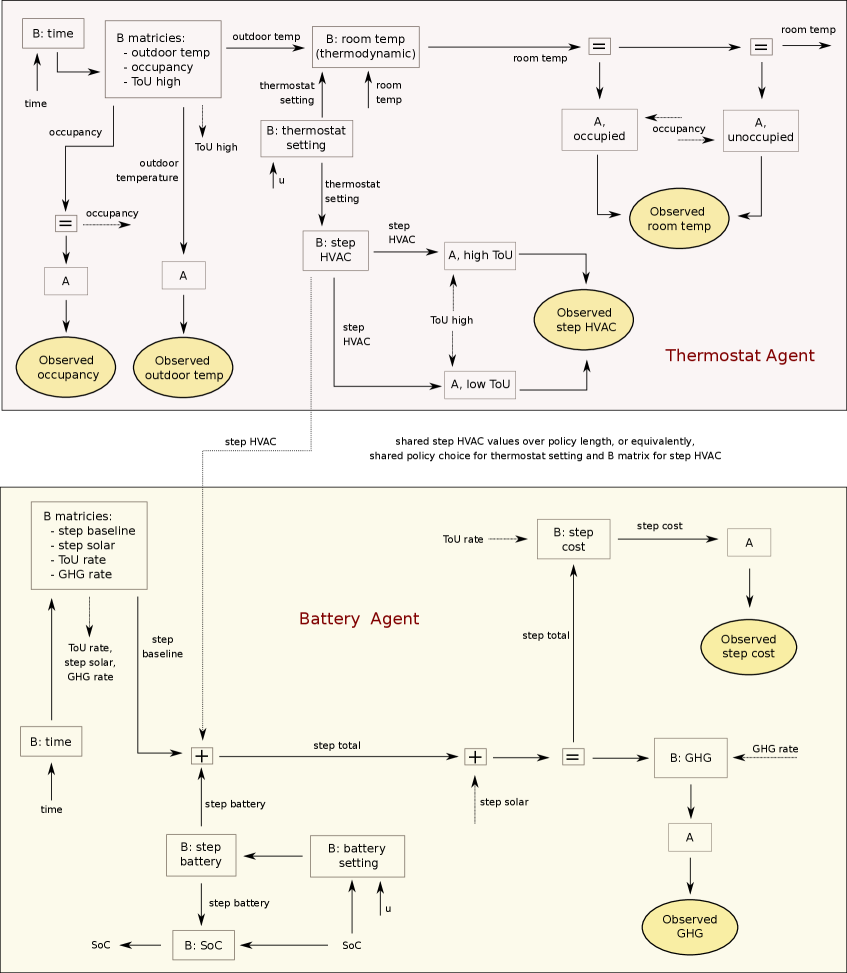

EcoNet isn't a single smart computer issuing commands to dumb devices. It's a household where devices are semi-autonomous agents that share information about their world models.

The thermostat knows the battery's upcoming charge level. The battery understands the thermostat's temperature preferences. They're not negotiating or voting; each is reasoning about a shared world and choosing actions that make sense given what the group knows. Coordination emerges naturally, not because a central authority mandates it, but because locally intelligent decisions respect the global situation.

This matters practically. Real homes have dozens of controllable devices: thermostats, water heaters, batteries, EV chargers, washers, dishwashers. Neighborhoods have hundreds of homes. Centralized control becomes a bottleneck. You can't reprogram the entire system every time you add a device. But with distributed coordination, a new device joins the information-sharing network, and everyone's reasoning updates automatically. The system scales.

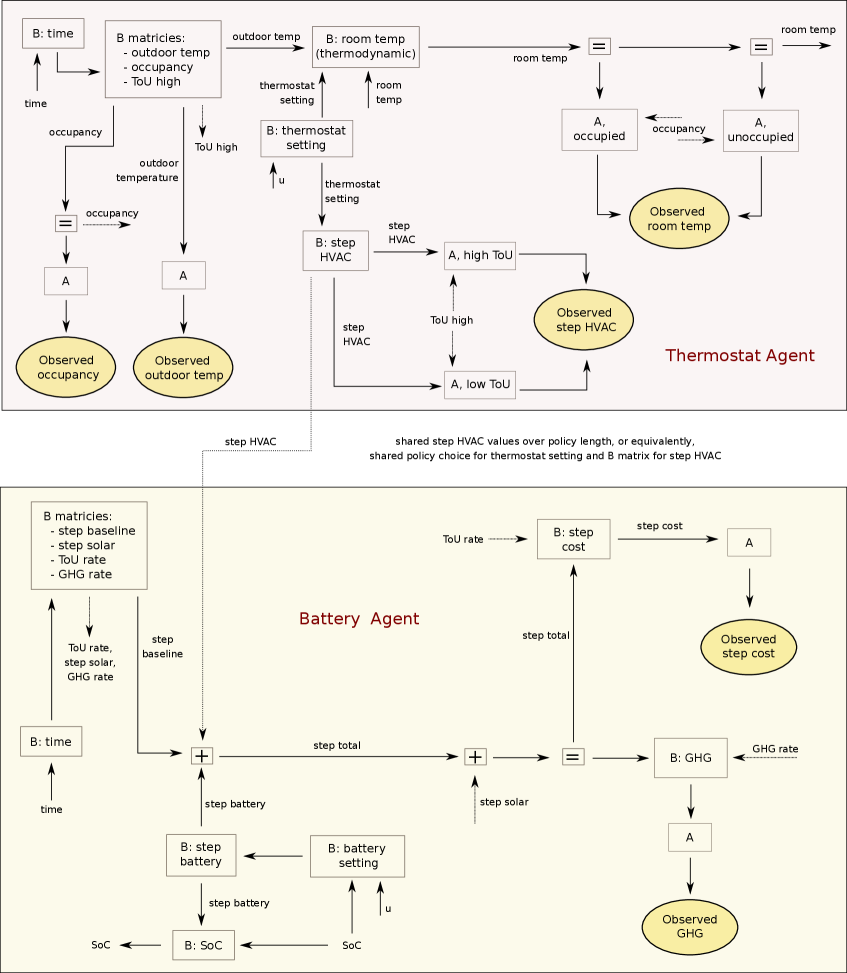

Pseudo-factor graph for two-agent EcoNet model. Squares AA and BB refer to likelihood and prior transition matrices.

Pseudo-factor graph for two-agent EcoNet model. Squares AA and BB refer to likelihood and prior transition matrices.

Figure 1 shows how two agents share information. The connections between the two sides of the factor graph represent the flow of information. Each agent maintains beliefs about its own state (battery charge, room temperature) and reasons about shared observations (time of day, electricity prices, weather). Coordination is structured information-sharing, not centralized commands. Adding a third agent or a tenth agent just extends this structure. The mathematics scale.

This kind of distributed reasoning connects to broader work on multi-agent energy systems. Work on multi-agent coordination in smart grids shows similar principles at the neighborhood level. And the belief-based approach aligns with energy-aware dynamic control, where systems adapt by reasoning about their internal state rather than following fixed rules.

What the system actually does

Theory is compelling, but does it work? The paper presents simulation results on realistic household scenarios. The system must simultaneously manage temperature comfort, minimize cost, and reduce emissions. The results reveal something subtle: EcoNet doesn't achieve perfection on any single goal. Room temperature deviates from target sometimes. Costs aren't minimized to the penny. The system gracefully balances all three, making intuitive tradeoffs.

When solar generation is high and the grid is clean, the system charges the battery and defers heating. Cheap energy is ahead. When evening peaks approach, consumption shifts away from that window. The reasoning is transparent and human-sensible.

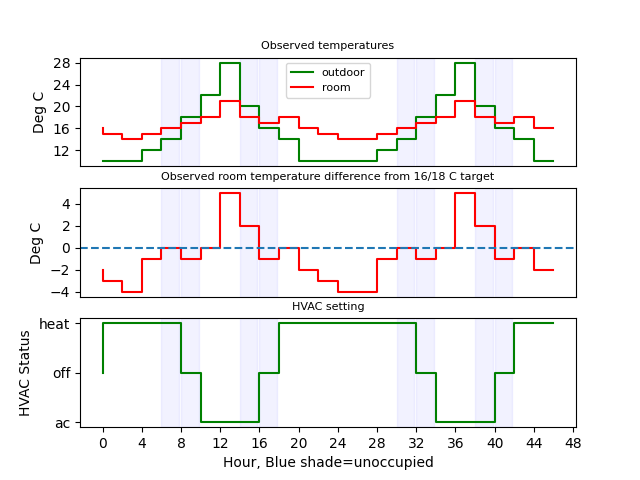

Outdoor and room temperatures, temperature deviations from target, and thermostat actions over time.

Outdoor and room temperatures (top), temperature deviations from target (middle), and thermostat actions (bottom).

Figure 4 shows the thermostat's real-time decisions. Notice that temperature deviates from target occasionally. The system isn't rigidly enforcing comfort. Instead, it trades comfort against other goals. Sometimes it lets the room cool slightly to avoid peak-hour heating. Other times, it heats aggressively because the grid is clean and cost is low. The pattern isn't random. It's systematically optimizing the tradeoff between conflicting objectives.

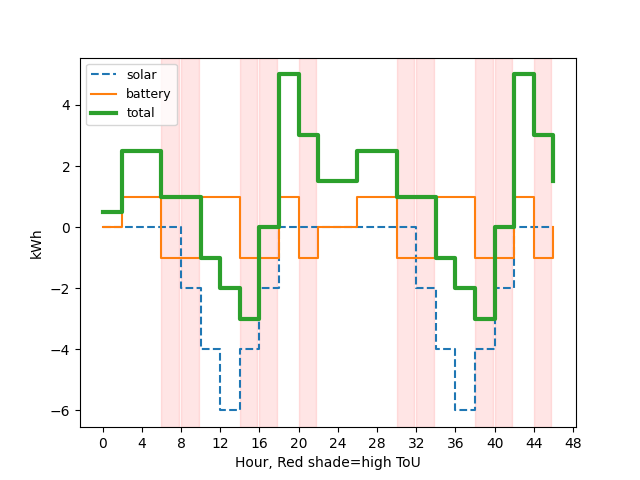

Agent beliefs about total, battery, and solar energy use.

Agent beliefs about total, battery, and solar energy use.

Figure 7 shows energy beliefs over time. Early in the simulation, the uncertainty bands are wide. The system doesn't yet understand energy flows. After days of observation, the bands tighten. The system learns to predict consumption and solar generation. This tightening uncertainty translates directly to better decisions.

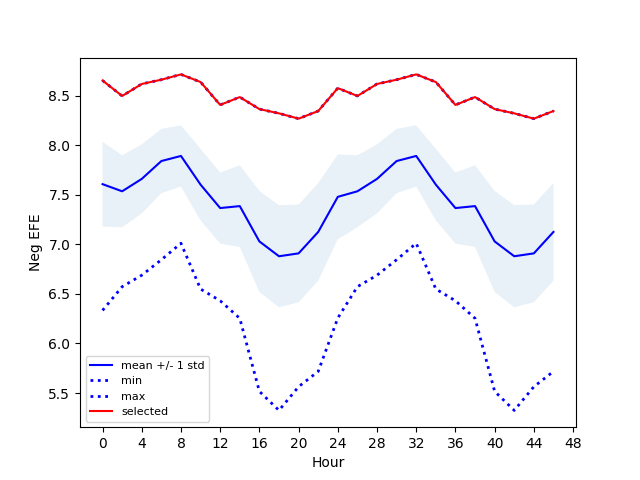

Distribution of negative expected free energy over different policies at each time step.

Distribution of negative expected free energy over different policies at each time step.

Figure 3 reveals the decision-making process itself. At each time step, the system evaluates candidate actions by calculating their expected free energy, a measure combining goal achievement and information gain. The distribution shows that some actions are clearly superior to others, but meaningful uncertainty remains. This isn't a system making confident optimal choices. It's making probabilistically justified choices given incomplete information.

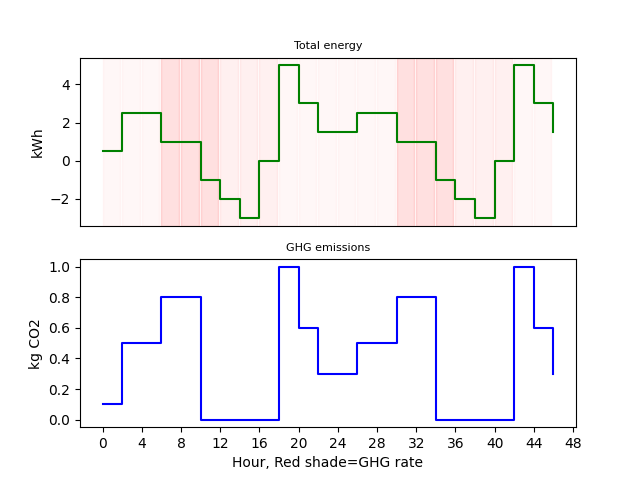

The emissions dimension deserves emphasis. Figure 8 shows the system learning when the grid is cleanest and dirtiest. The heatmap of grid-associated greenhouse gas rates reveals strong patterns: mornings are cleaner, evenings are dirtier, midday depends on solar. The system observes this structure and adjusts. When the grid is clean, it's more willing to shift consumption forward. When the grid is dirty, it defers or reduces consumption.

Agent beliefs about total energy use versus grid-associated GHG rates and resulting emissions.

Agent beliefs about total energy use versus grid-associated GHG rates (top) and resulting emissions (bottom, deeper red indicates higher emissions).

This behavior isn't hardcoded. The system wasn't told "the grid is dirtiest at 7 PM." It learned this from observations and reasoned accordingly. As grids decarbonize or change their generation mix, the system would adapt automatically. A coal plant retirement or a new solar farm would shift the emissions patterns the system observes, and its behavior would track the new reality.

Convergence and adaptation

The learning process works, but does it converge? Does the system's reasoning actually improve toward optimal behavior, or does it just make locally sensible decisions that compound errors over time?

Figure 9 answers this decisively. Over 40 days, negative expected free energy drops monotonically. The system isn't spinning its wheels. It's getting genuinely better at achieving its goals. After 40 days, its ability to maintain target room temperature matches that of a deterministic model built by hand. The system has learned the thermal dynamics of the house well enough that its probabilistic reasoning performs as well as a perfect model.

Learning the room temperature transition matrix, showing dropping negative expected free energy and convergence to deterministic performance.

Learning the room temperature transition matrix, showing dropping negative expected free energy (left) and convergence to deterministic performance (right).

This convergence matters because it validates the fundamental approach. The system isn't just making decisions that seem reasonable in the moment. It's discovering better models of the world and using those models to make systematically better decisions. That's learning in the meaningful sense.

The adaptability is equally important. When circumstances change, the system doesn't cling to outdated beliefs. It detects divergence between predictions and observations, and updates. Figure 6 shows this concretely: when the utility changes the time-of-use rate schedule, the system's behavior adjusts within days. The old beliefs become less predictive. New patterns emerge from the observations. The system learns the new pattern and acts accordingly.

This is resilience without brittleness. Many energy management systems fail when their assumptions break. A solar forecast model trained on typical weather becomes useless in an unprecedented heat wave. A demand-response algorithm designed for one rate structure creates perverse incentives under a different one. EcoNet handles these changes because it's fundamentally a belief-updating system, not a rule-following one. When the world changes, the beliefs update, and behavior adapts.

A framework for reasoning under uncertainty

EcoNet reveals something elegant about household energy management: the problem isn't fundamentally about optimization or control in the traditional sense. It's about reasoning under uncertainty while balancing competing goals. By shifting from "find the optimal schedule given fixed priorities" to "maintain beliefs about the world and choose actions that move toward desired outcomes given those beliefs," the system becomes flexible, learnable, and scalable.

The approach isn't limited to households. Similar principles apply at the neighborhood and grid scales, as shown in work on multi-agent energy coordination. And the broader framework connects to active inference in other control domains, where belief-based reasoning outperforms rigid optimization when goals conflict or uncertainty is substantial.

As renewable energy scales and household devices proliferate, this kind of probabilistic reasoning becomes essential. The future grid will have millions of flexible demand resources, each with local knowledge and local goals. No central authority can compute the optimal global schedule. Instead, distributed agents must reason locally about shared information and coordinate through their collective beliefs. EcoNet demonstrates that this approach works, and improves over time.

Human cognition evolved to handle exactly this kind of problem: navigating an uncertain world with conflicting drives and desires, learning better models, and adapting when the world changes. Household energy management, it turns out, requires the same kind of reasoning.