Overview

- Training large language models on massive datasets is expensive and resource-intensive

- Creating smaller, high-quality synthetic datasets could reduce these costs while maintaining performance

- The paper explores how to generate diverse synthetic data directly in the feature space where language models operate

- Key insight: you don't need as much data if the data you have is well-distributed and representative

- The approach measures how well synthetic data generalizes to unseen examples

- Working in feature space (the internal representations models use) rather than raw text simplifies the synthesis process

Plain English Explanation

Imagine you're training someone to recognize different types of fruit. You could show them thousands of photos of apples, oranges, and bananas. Or you could show them a smaller, carefully curated set that captures the essential visual differences between fruits. The smaller set works just as well if it covers the right variety.

That's essentially what this paper tackles. Training modern large language models requires feeding them enormous amounts of text data. This costs money, time, and computational resources. The researchers asked: what if we could create less data that works better?

The trick is understanding what "better" means. Rather than creating synthetic text (which is hard to get right), they work in feature space—think of this as the internal language the model uses to understand meaning. If you could directly create good representative points in this space, you sidestep the difficulty of generating natural-sounding text.

The paper measures whether synthetic data generalizes well by checking if it covers the important variations in real data. It's like asking: does this smaller fruit collection actually represent all the important differences, or did we miss something crucial?

Key Findings

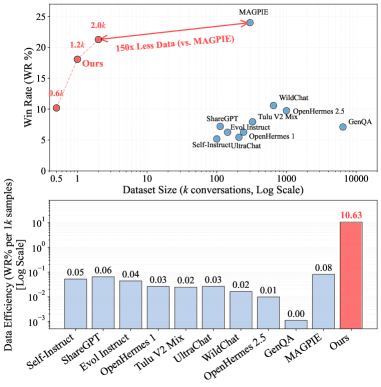

- Synthetic data in feature space requires significantly less volume than training on original datasets while maintaining similar performance levels

- The method successfully reduces the distribution gap between synthetic and real data through targeted feature space manipulation

- Diversity in synthetic data matters more than quantity—well-distributed smaller datasets outperform larger but homogeneous ones

- The generalization of synthetic data can be measured and predicted before using it for training

- The approach works across multiple downstream tasks, showing that synthetic data created this way transfers effectively

Technical Explanation

The researchers developed a framework that operates in two main stages. First, they measure generalization potential by analyzing how well candidate synthetic data would cover the distribution of real data. This involves computing metrics that capture whether the synthetic features adequately represent the diversity present in the original dataset.

Second, they reduce the distribution gap between real and synthetic features through iterative refinement. This isn't random generation—the method strategically places synthetic points in feature space to maximize coverage of important regions while maintaining diversity.

The architecture leverages the existing representations from language models rather than trying to reconstruct text. This is computationally efficient because you're working with compressed, meaningful representations rather than generating billions of tokens.

The experiments compare models trained on reduced synthetic datasets against baselines trained on full datasets. They measure performance across various tasks to verify that quality truly substitutes for quantity. The key innovation is formulating the synthesis process in a way that's both theoretically motivated and practically implementable.

Implications for the Field

This work addresses a real bottleneck in machine learning: data acquisition and preparation. If synthetic data can be created efficiently in feature space with fewer examples, it could democratize access to powerful models by reducing computational requirements. Organizations without massive data budgets could train competitive models more affordably.

The approach also suggests that our intuitions about "more data is always better" need refinement. The paper demonstrates that thoughtfully constructed smaller datasets can achieve equivalent results, which could reshape how we think about data collection and preparation in machine learning.

Critical Analysis

The research makes strong assumptions about feature space representation that may not hold universally across different model architectures or domains. The method depends on the quality of features the underlying language model produces—if those representations are biased or incomplete, the synthetic data inherits those limitations.

One concern the paper doesn't fully address: synthetic data created this way is still constrained by what the base model can represent. You can't create truly novel concepts the model hasn't encountered; you're essentially remixing existing patterns. This might limit the approach for genuinely innovative or rare scenarios.

The paper also leaves questions about how much domain-specific tuning is required. The generalization claims are strong, but it's unclear whether the same approach works equally well for specialized domains like legal documents or medical literature where nuance matters significantly.

Additionally, the measurement of generalization relies on statistical metrics that capture distribution coverage. These metrics might miss edge cases or long-tail phenomena that matter in real applications but are statistically rare. A model might score well on distribution coverage while still failing on unusual but important examples.

The computational cost of the synthesis process itself deserves scrutiny. While the paper focuses on savings from using less data, the cost of intelligently generating and selecting synthetic features should be factored into total efficiency claims.

Conclusion

This paper presents a practical approach to a significant problem: reducing the data requirements for training powerful language models. By working in feature space rather than raw text, the researchers show that smaller, carefully constructed synthetic datasets can match the performance of much larger training sets.

The core insight—that diversity and distribution coverage matter more than volume—challenges conventional wisdom about data requirements. For organizations building language models, this opens possibilities for more efficient training pipelines. For the broader field, it suggests that future progress might come from smarter data curation rather than endlessly scaling up data collection.

The work remains exploratory in some dimensions, but it points toward a future where training advanced models becomes less data-hungry and more accessible. As computational efficiency becomes increasingly important, understanding how to do more with less takes on heightened significance.

This is a Plain English Papers summary of a research paper called Less is Enough: Synthesizing Diverse Data in Feature Space of LLMs. If you like these kinds of analysis, join AIModels.fyi or follow us on Twitter.