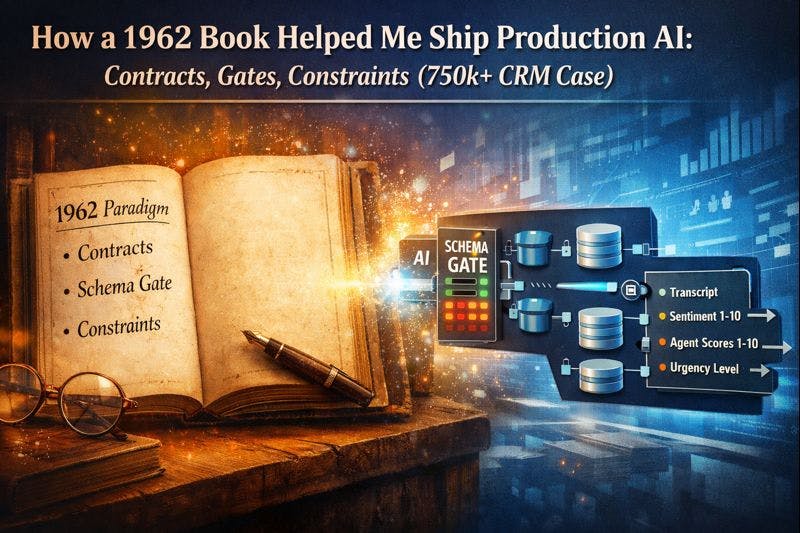

A book first published in 1962—Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions—isn’t where you’d expect to find guidance for shipping production AI. But Kuhn’s core point about paradigms clicked instantly for me: reliability starts when you make your “world” explicit—what exists, what’s allowed, what counts as evidence—and then enforce it. That’s exactly what I needed to migrate 750k+ CRM objects and build a post-hangup VoIP pipeline where transcripts, summaries, and 1–10 scoring don’t drift into inconsistent interpretations.

I’m what real developers might politely call a “vibe-coder.”

I can spend hours unpacking geopolitical risk or debating why the EU defaults to caution. But if you ask me about Python memory management, I’ll assume you mean my ability to remember what I named a variable last week.

I’m not a Software Engineer. I’m a Strategic Product Lead and a General Manager. I define the what and the why, align stakeholders, and I’m accountable for whether a system behaves predictably once it leaves the sandbox. I also lecture in Business Problem Solving, so I tend to approach technology as a governance problem: clarify the objective, specify the constraints, then build something that fails safely.

Two years ago, I started using AI to prototype quickly—mostly to test whether an idea had legs. It worked until the project stopped being a prototype.

Because the requirement wasn’t “build a custom CRM.” It was:

- migrate 122,000 contacts

- migrate 160,000 leads

- migrate ~500,000 notes and tasks

- integrate our VoIP center so that every call, within seconds after hangup, produces:

- a complete transcript

- a summary

- a sentiment score (1–10)

- five agent-performance scores (1–10): solution effectiveness, professionalism, script adherence, procedure adherence, clarity

- an urgency level for escalation

At this size, ambiguity doesn’t stay local. A small mapping inconsistency becomes thousands of questionable rows. A slightly inconsistent output format becomes a long-term reporting problem. The cost isn’t just technical—it’s organizational: people stop trusting the CRM.

AI sped up prototyping. Production reliability still requires boring engineering discipline: contracts, validation, idempotency, and constraints.

The point of this article is not that I “solved AI.” The point is that I stopped treating model output as helpful text and started treating it as untrusted input—governed by explicit definitions.

For clarity: “we” refers to my workflow—me and three LLMs used in parallel for critique and cross-checking. Final design decisions and enforcement mechanisms remained human-owned.

Ontology, in the International Relations sense (Kuhn + a quick example)

In International Relations, it helps to borrow Thomas Kuhn’s idea of a paradigm: a shared framework that tells a community what counts as a legitimate problem, what counts as evidence, and what a “good” explanation looks like.

An ontology is the paradigm’s inventory and rulebook: what entities exist in your analysis, what relationships matter, and what properties are allowed to vary. If you don’t make that explicit, people can use the same words and still analyze different phenomena.

A quick example: take the same event—say, a border crisis.

- Under a realist paradigm, the ontology centers on states as primary actors, material capabilities, balance of power, and credible threats. The analysis asks: Who has leverage? What are the incentives? What capabilities change the payoff structure?

- Under a constructivist paradigm, the ontology expands to identities, norms, shared meanings, and legitimacy. The analysis asks: How are interests constructed? What narratives make escalation acceptable—or taboo? Which norms constrain action?

Same event. Different ontology. Different variables. Different “explanations.”

Tech analogy: realism vs constructivism is like two incompatible schemas. Same input, different fields, different allowed states—so you should expect different outputs.

That’s exactly what happens in production AI and data migration. If you don’t explicitly define the entities, relationships, and admissible states in your system, you don’t get one consistent dataset—you get parallel interpretations that collide later. The model (and sometimes the humans) will quietly invent meanings.

So we made the system’s world explicit. Then we enforced it.

The reliability pattern: contract → gate → constraints

Nothing here is novel engineering. An experienced engineer will recognize familiar patterns: contract-first design, defensive validation, and strict constraints.

What was personally novel (to me) is that an IR habit—obsession with definitions and enforcement—got me to the boring, correct patterns faster than “prompting harder” ever could.

The pattern we implemented was simple:

- Output contract: define exactly what the model is allowed to output

- Schema gate: validate model output before it can touch the database

- Database constraints: enforce the same rules at rest, so invalid data can’t accumulate

It’s not “trust the model.” It’s “verify the payload.”

Architecture: post-hangup, then enforce

We designed the pipeline around one clean boundary condition: hangup.

The call ends, the audio artifact is finalized, and only then do we run transcription and scoring. Operationally, a call is only considered “closed” when its insight record is persisted (idempotent retries handle transient failures).

High-level flow:

- hangup event triggers processing (idempotent by

call_id) - speech-to-text produces a complete transcript

- transcript goes to the insights engine with the policy/protocol (the output contract and scoring rules)

- the model returns a structured payload

- a schema gate validates required fields, types, and 1–10 ranges

- only validated payloads get stored; non-compliant payloads go to retry/DLQ

This is where “AI” stops being an assistant and becomes a component in a production system: the output becomes a transaction, not a suggestion.

Define the world: the output contract

Instead of asking for “sentiment,” we defined an explicit output contract:

transcript_text(text)summary_text(text)sentiment_score(integer 1..10)agent_solution_score(integer 1..10)agent_professionalism(integer 1..10)agent_script_adherence(integer 1..10)agent_procedure_adherence(integer 1..10)agent_clarity(integer 1..10)urgency_level(enum: Low / Medium / High)key_phrases(json)confidence_score(optional float 0..1)analyzed_at(timestamp)model_version,schema_version(strings)

Anything outside the contract is invalid. Not “close enough.” Invalid.

This is the core idea: you don’t make model outputs reliable by asking nicely. You make them reliable by treating them as untrusted input until they pass a gate.

Scale: your database needs to be strict, not optimistic

At 50 rows, “we’ll fix it later” is a workflow. At 750,000+ objects, it’s a myth.

So we added a second enforcement layer: the database. Not as a backup plan—as a principle. If something doesn’t fit, the system should refuse it rather than store it and let it rot.

We enforced two invariants.

1) Enforce 1:1 mechanically

If you claim “every call gets insights,” make it a database invariant:

CALL_INSIGHTS.call_id is both PK and FK to CALL_LOG.call_id

This is not a philosophical statement. It’s a mechanical guarantee.

2) Constrain scoring at rest

We store:

- sentiment score as

CHECK 1..10 - each agent metric as

CHECK 1..10 - urgency as a controlled enum/level

- optional confidence for auditing

model_versionandschema_versionso the system stays explainable over time

We don’t treat a 1–10 score as ground truth. It’s anchored to evidence (transcript + summary) and audited against downstream reality (lead evolution, resolution outcomes, escalation events). When the signal disagrees with outcomes, it’s traceable and correctable.

In IR terms: the “measurement” only makes sense because the ontology is explicit. You know what the object is (the call), what its properties are (scores, urgency), and what counts as a change of state (lead evolution, escalation, closure). Without that, a number is just a vibe.

Migration without semantic corruption

The VoIP pipeline was only half the story. The other half was moving the dataset into a custom CRM without importing legacy ambiguity.

The biggest risk in CRM migration isn’t missing data. It’s meaning drift—what I call semantic corruption:

- two systems use the same label for different concepts

- different teams treat the same field as different things

- free-text “stages” become permanent, un-auditable taxonomy

We handled migration with the same ontology-first logic.

The schema of truth

Before scripts, we defined the target data model as a schema of truth:

- explicit entities (Contact, Lead, Call, Call Insights, Notes/Tasks)

- explicit relations (FKs, cardinality, invariants)

- explicit admissible states (enums and allowed transitions)

This is ontology in the IR sense: a declared set of entities, relations, and admissible states—so your mapping can’t quietly change the phenomenon you think you are measuring.

Canonical IDs and idempotent imports

A migration without canonical identifiers is a one-time import you can’t reproduce.

We enforced stable identity:

legacy_system+legacy_idper object- uniqueness constraints

- replay-safe (idempotent) writes

That allowed reprocessing without duplicates and enabled corrections without manual surgery.

Quarantine, don’t “best effort”

Ugly data exists. The question is whether you hide it.

We split incoming records into:

- valid → import

- repairable → normalize + log

- invalid → quarantine with explicit reasons

At scale, rejecting invalid data isn’t being “harsh.” It’s preventing silent rot.

Tooling note (brief and honest)

We use OpenAI in production, selected after comparative testing against Gemini about five months ago. This isn’t a lab write-up—we’re writing after the pipeline has been running long enough for us to validate operational usefulness.

The transferable idea is the pattern: contract + gate + database constraints, not the vendor.

A quick note on privacy (non-negotiable): Call transcripts are sensitive data. We apply role-based access, retention policies, and redaction where needed. The technical architecture is only useful if governance around data access is equally strict.

Takeaways (the practical checklist)

If you’re building AI features into a system people will rely on:

- treat model output as untrusted input

- define an output contract (fields, types, ranges)

- validate at the boundary (schema gate)

- enforce at rest (database constraints)

- version definitions (schema/model versions) for explainability

- design around a clean boundary condition (for us: post-hangup)

- keep evidence (transcript/summary) so scores are traceable and correctable

You don’t need to become a data scientist to do this. But you do need to stop thinking like a prompt writer and start thinking like a system designer.

Reference(s)

Kuhn, T. S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (originally published 1962). University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226458106.001.0001