This is a Plain English Papers summary of a research paper called Being-H0.5: Scaling Human-Centric Robot Learning for Cross-Embodiment Generalization.

Overview

- The paper presents Being-H0.5, a robot learning system that trains on human demonstrations to help robots work across different body types

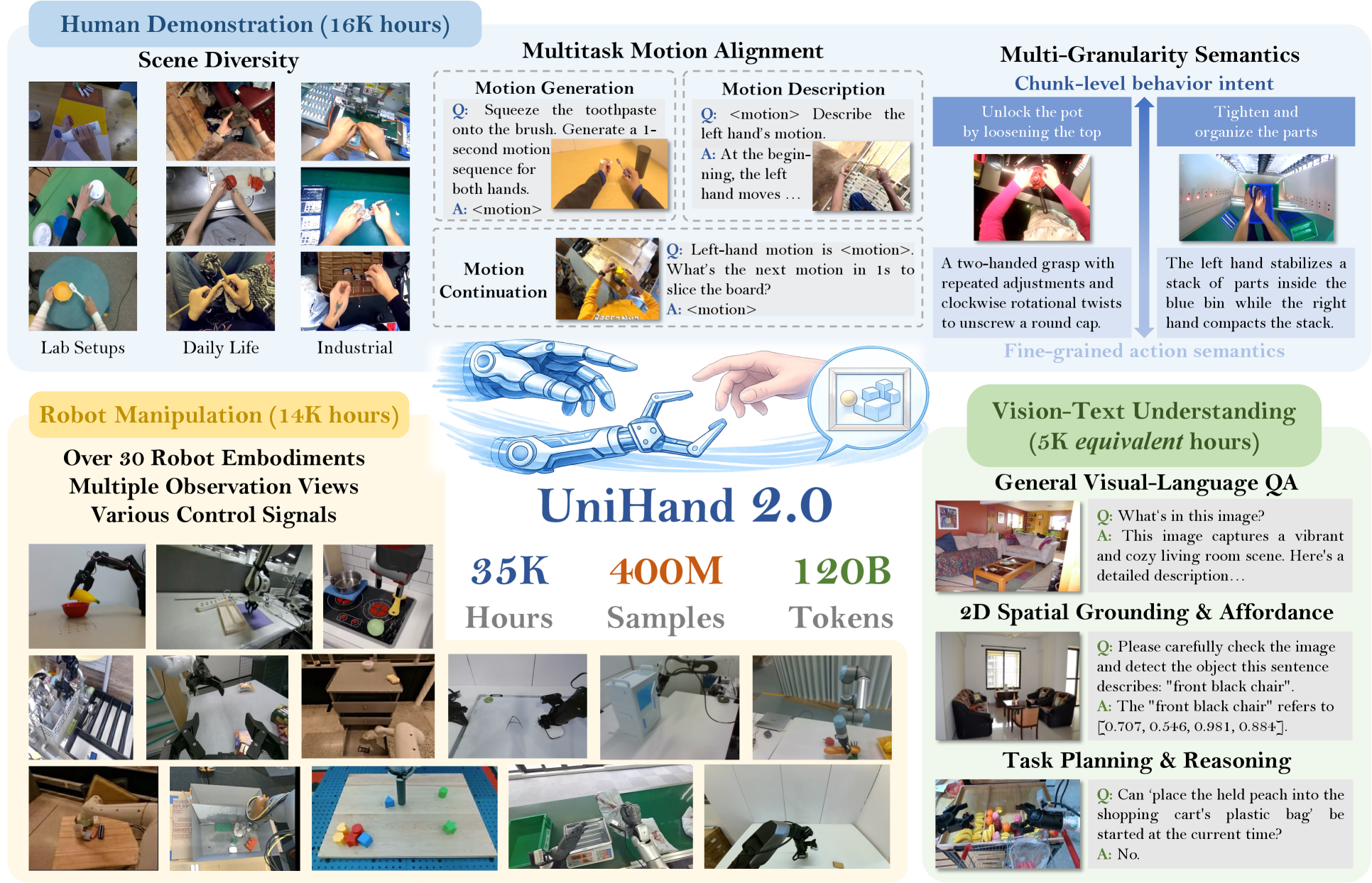

- The approach uses a large dataset of human hand movements called UniHand-2.0

- The system learns to translate human actions into instructions that different robot embodiments can follow

- Training on human data helps robots generalize better than training only on robot-specific data

- The method achieves strong performance across multiple robot designs without task-specific retraining

Plain English Explanation

Think of learning to tie your shoes. If you watched someone else tie theirs first, you'd pick up the basic idea of how the motion should flow. You could then adapt it to your own hands, even if yours are different sizes or shapes. That's the core idea here.

Robots face a similar challenge. Different robots have different designs—different arm lengths, different numbers of joints, different grippers. Traditionally, you'd need to train each robot separately on its own tasks. But the researchers realized something: human demonstrations contain something deeper than just robot-specific movements. Humans solving a task reveal the essential structure of what needs to happen.

By training on large-scale human hand demonstration data, the system learns general principles about how to accomplish tasks. Then when you ask it to work with a specific robot, it can translate those principles into that robot's language. It's like learning the underlying concept of a task rather than just memorizing a specific execution.

The key insight is that human-centric learning acts as a bridge. Humans and robots are different enough that you can't just copy human movements directly. But they're similar enough that the fundamental task understanding transfers. This turns out to be a powerful lever for getting robots to work across many different physical designs.

Key Findings

- The UniHand-2.0 dataset contains significantly more human hand demonstration data than previous collections, providing richer training material for learning task principles

- Models trained on human data generalize to multiple robot embodiments without embodiment-specific fine-tuning, showing that human demonstrations provide generalizable task knowledge

- Being-H0.5 achieves higher success rates across diverse robot platforms compared to baseline approaches trained only on robot data

- The approach demonstrates that scaling up human demonstration data improves cross-embodiment transfer learning capabilities

- Human-centric pretraining provides a more stable foundation for adaptation to new embodiments than purely robot-centric approaches

Technical Explanation

The system works in stages. First, the researchers collected a large dataset of human hand movements performing various manipulation tasks. This isn't just video—it includes precise tracking of hand position and finger movements, capturing what we might call the "grammar" of how humans accomplish physical tasks.

The UniHand-2.0 dataset serves as the foundation. Rather than collecting demonstrations from every robot they wanted to support, they leveraged the insight that human movements encode general task principles. The system learns to represent these tasks in a way that isn't tied to any particular body.

When deploying to a specific robot, the approach uses what researchers call embodiment-aware adaptation. The model receives information about the robot's physical capabilities—how many joints it has, what its reach is, how its gripper works. Using this information, it translates the learned task principles into actions that particular robot can execute. It's similar to how you might translate cooking instructions for a kitchen with different tools—the core approach adapts to available equipment.

The architecture incorporates vision-language-action components that let the system understand both what it sees and what task it needs to accomplish. The human demonstration data provides a rich signal about how perception connects to action, which helps the model build stronger representations.

Training happens in two phases. First, the model learns from human data to build general task understanding. Then, with access to a small amount of robot-specific data, it adapts those learned principles to the particular robot's physical constraints and capabilities. This two-stage approach means you don't need massive amounts of robot data for each new embodiment.

Critical Analysis

The research makes a compelling case for human-centric learning, but several questions remain worth examining.

The generalization claims assume that human task structure maps onto robot task structure in meaningful ways. But humans and robots have fundamentally different constraints. Humans rely heavily on haptic feedback and proprioception that robots might not have. The extent to which human task solutions actually represent optimal solutions for robots—rather than just useful approximations—deserves scrutiny. A robot with very different physical capabilities might need to solve tasks in fundamentally different ways.

The paper's evaluation focuses on manipulation tasks that humans also perform. It's unclear how well this approach would extend to tasks robots can do but humans cannot, or to entirely different physical domains. This represents a real boundary on where human-centric learning provides value.

There's also the question of data quality and bias. The UniHand-2.0 dataset contains human demonstrations, which means it encodes human biases, limitations, and inefficiencies. Is the system learning general task principles, or is it learning specifically human ways of solving tasks? Some robot tasks might be solved more efficiently in ways humans would never attempt.

Regarding embodiment scaling laws, the research doesn't fully characterize how performance degrades as embodiments become more different from humans. At what point does a robot become different enough that human demonstrations stop providing value? The paper would benefit from clearer analysis of these limits.

The comparison baselines matter too. Understanding exactly how much improvement comes from human data versus simply from the scale of the UniHand-2.0 dataset compared to purely robot datasets would strengthen the claims.

Conclusion

Being-H0.5 addresses a real problem in robotics: the need to train systems across multiple robot designs without starting from scratch for each one. By anchoring learning in human demonstrations, the approach finds a middle ground between completely general learning and completely embodiment-specific training.

The core contribution is practical and elegant—if you want robots to work across different body types, train them first on what humans teach you about tasks, then adapt to specific robot embodiments. This vision-language-action methodology sidesteps some thorny problems in robotics by leveraging the existing abundance of human task demonstrations.

For the field, this suggests that robotics doesn't need to operate in isolation. Human knowledge and demonstrations have value not because robots should copy humans, but because humans reveal the underlying structure of tasks. As robotics scales toward more diverse embodiments and applications, this insight becomes increasingly valuable. The research points toward a future where we build more capable robots not by engineering each one separately, but by learning what tasks fundamentally require and letting different embodiments solve them in their own ways.

If you like these kinds of analyses, join AIModels.fyi or follow us on Twitter.