Table of Links

- Current and past basic income experiments

- Financing a basic income program

- Finding alternative solutions

- Conclusion, Acknowledgment, and References

4. Finding alternative solutions

From these examples, we can see that the massive expenditure on UBI is neither economically efficient nor socially equitable. More importantly, it does not address the problem of large-scale displacement due to automation. With nearly half of all jobs at risk of being automated over the next 20 years, it is in urgent need to establish systematic transition of workers from low and mid-level into high-level skilled professions in developing and emerging industries like AI, robotics and blockchain, as well as non-tech sectors that are not easily replicated by machines. As the old saying goes, “it is better to teach a man how to fish than to give him a bucket of fish. This requires an “automation-proof” education that truly prepares and adapts the labor force for fundamental changes in the workplace. As automation is part of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and as a similar trend with the previous three revolutions, the number of new jobs created would outweigh the ones displaced by machines. In the 1980s, when the personal computer was introduced, concerns regarding its threat of replacing people’s work arose. Until 2015, the introduction of the PC has indeed displaced 3.5 million jobs in the US— but at the same time, it has created 19.2 million new ones (Bughin et al., 2017). Therefore, the government’s education policies to ensure the future workforce’s transition into new emerging positions are critically crucial. This could be done via these approaches:

Firstly, the government needs to provide more vocational training that will enable displaced workers to enter highgrowth sectors like renewable energy, which is expected to add 20 million new jobs by 2030, or the healthcare industry, where 80-130 million new opportunities are available by 2030 (Renner et al., 2008).

Secondly, as low-skilled jobs are replaced by robots, more jobs will shift to high-level industries: “80% of the new jobs created will require a graduate-level education or equivalent” (Talwar et al., 2018). Therefore, the government needs to encourage employees to continue higher education while still in employment to adapt to the higher skill level demanded. As historically proven, higher educational attainment is linked with lower levels of unemployment, for low skilled workers are more susceptible to becoming unemployed during economic downturns, as shown in the data from the Labor Department in Figure 2.

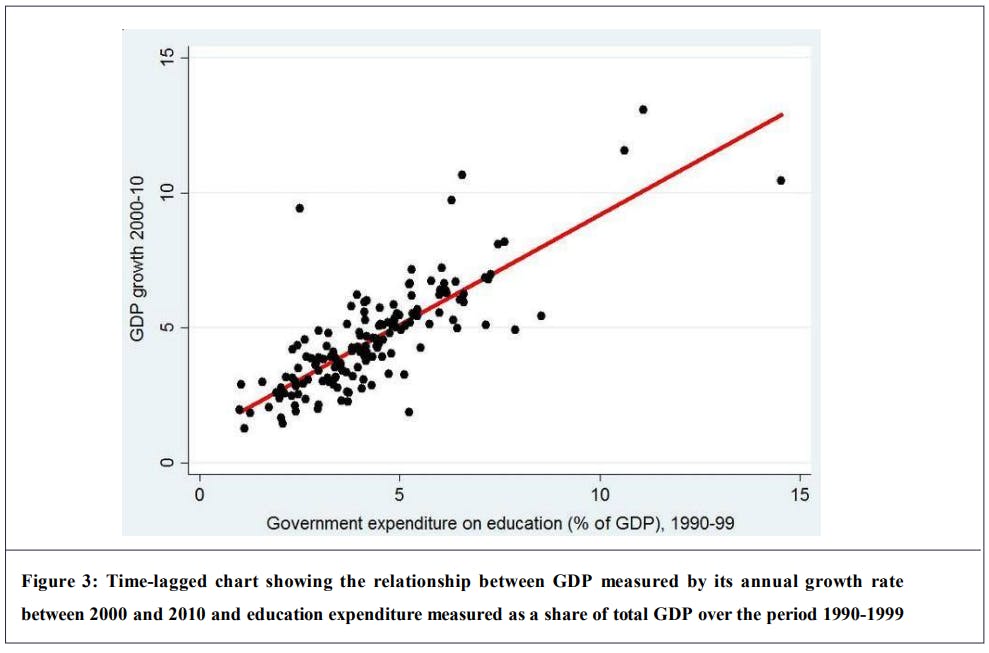

Thirdly, schools will also need to foster critical thinking, creativity, emotional intelligence, flexibility, and cultural agility—skills that cannot be replicated by machines. This would require an overhaul of our education system, demanding considerable funding from the government. Education, after all, is a much more affordable investment compared to UBI. The World Bank’s World Development Indicators (2010), as shown in Figure 3, estimates that for every dollar the government spends on education, GDP grows on average by $20.

5. Conclusion

Results from two prominent UBI-analogous experiments show that granting a sum of money unconditionally to a population does not have a substantial nor positive effects on the employability, income, and other measures of living standards. Further investigations into the costs of implementation of UBI in addition to existing welfare programs suggest an exorbitant cost that would significantly enlarge a country’s budget while the marginal benefit is minimal. In the hypothesis of replacing the welfare state with a UBI, living standard metrics such as poverty rate worsen substantially. We then consider and make a case for the alternative policy of retaining existing welfare programs with an emphasis on increasing funding for the education system and training initiatives for displaced and low-skilled workers.

Acknowledgment

An early version of this manuscript won a high commendation from the Royal Economic Society and was featured among the Young Economist of the Year honorees in late 2019.

References

Frey, Carl, Benedikt, and Osborne, Michael, A. (2017). The future of employment: how susceptible are jobs to computerisation?. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 114 (January 1), 254-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.techfore.2016.08.019.

Frey, Carl Benedikt, M. Osbourne, and Craig S. Holmes. (2016). Technology at work v2.0: the future is not what it used to be. Technology at Work Citi GPS. Oxford Martin School, January, http://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/ reports/Citi_GPS_Technology_Work_2.pdf.

Howden, Lindsay M., and Julie A. Meyer. (2010). Age and sex composition: 2010. Census Briefs. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-03.pdf

Jacques Bughin, James Manyika, Susan Lund, Michael Chui, Jonathan Woetzel, Parul Batra, Ryan Ko, and Saurabh Sanghvi. (2017). Jobs lost, jobs gained: Workforce transitions in a time of automation. McKinsey Global Institute. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/public%20and%20social%20sector/our%20insights/ what%20the%20future%20of%20work%20will%20mean%20for%20jobs%20skills%20and%20wages/mgi-jobslost-jobs-gained-executive-summary-december-6-2017.pdf

Kopits, Steven. (2017). Corporate tax rates and economic growth. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Energy Advisors, September 2, 2017. http://www.prienga.com/blog/2017/9/2/corporate-tax-rates-and-economic-growth.

Kansaneläkelaitos. (2019). Objectives and Implementation of the Basic Income Experiment. https://www.kela.fi/web/en/ basic-income-objectives-and-implementation

Olli Kangas, Signe Jauhiainen, Miska Simanainen, and Minna Ylikännö. (2019). The basic income experiment 2017-2018 in Finland: Preliminary results. Serial publication. Reports and Memorandums of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health 2019:9. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-00-4035-2.

Reed, Howard. and Lansley, Stewart. (2016) . Universal basic income: an idea whose time has come?. London: Compass. https://www.compassonline.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/UniversalBasicIncomeByCompass-Spreads.pdf

Renner, Michael., Sean, Sweeney. and Jill, Kubit. (2008). Green jobs: towards decent work in a sustainable, low-carbon world. Report. Nairobi: United NatiReedons Environment Programme. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/ —ed_emp/—emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_158727.pdf.

Sautoy, Marcus, du. (2019). Could ai replace human writers?. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/5fc7fc52- 4720-11e9-b83b-0c525dad548f

Talwar, Rohit., Steve, Wells., Alexandra, Whittington., April, Koury. and Helena Calle. (2018). Education and employment and the response to automation. University World News. https://www.universityworldnews.com/ post.php?story=20180718063505798

West, Richard W. (1980). The effects on the labor supply of young nonheads. The Journal of Human Resources. 15(4), 574-90. https://doi.org/10.2307/145402.

Wiederspan, Jessica., Elizabeth, Rhodes. and Luke, Shaefer. H. (2015). Expanding the discourse on antipoverty policy: reconsidering a negative income tax. Journal of Poverty. 19(2) 218-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2014.991889.

Widerquist, Karl, Noguera, José, A., Vanderborght, Y. and Wispelaere, J.D. (2013). Basic income: An anthology of contemporary research. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

World Bank Group. (2010). World Development Indicators. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-developmentindicators.

Author:

(1) Le Dong Hai Nguyen, School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University, 3700 O St NW, Washington, DC 20057 (ln406@georgetown.edu).

This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED license.