I keep seeing the same mismatch in digital mental health.

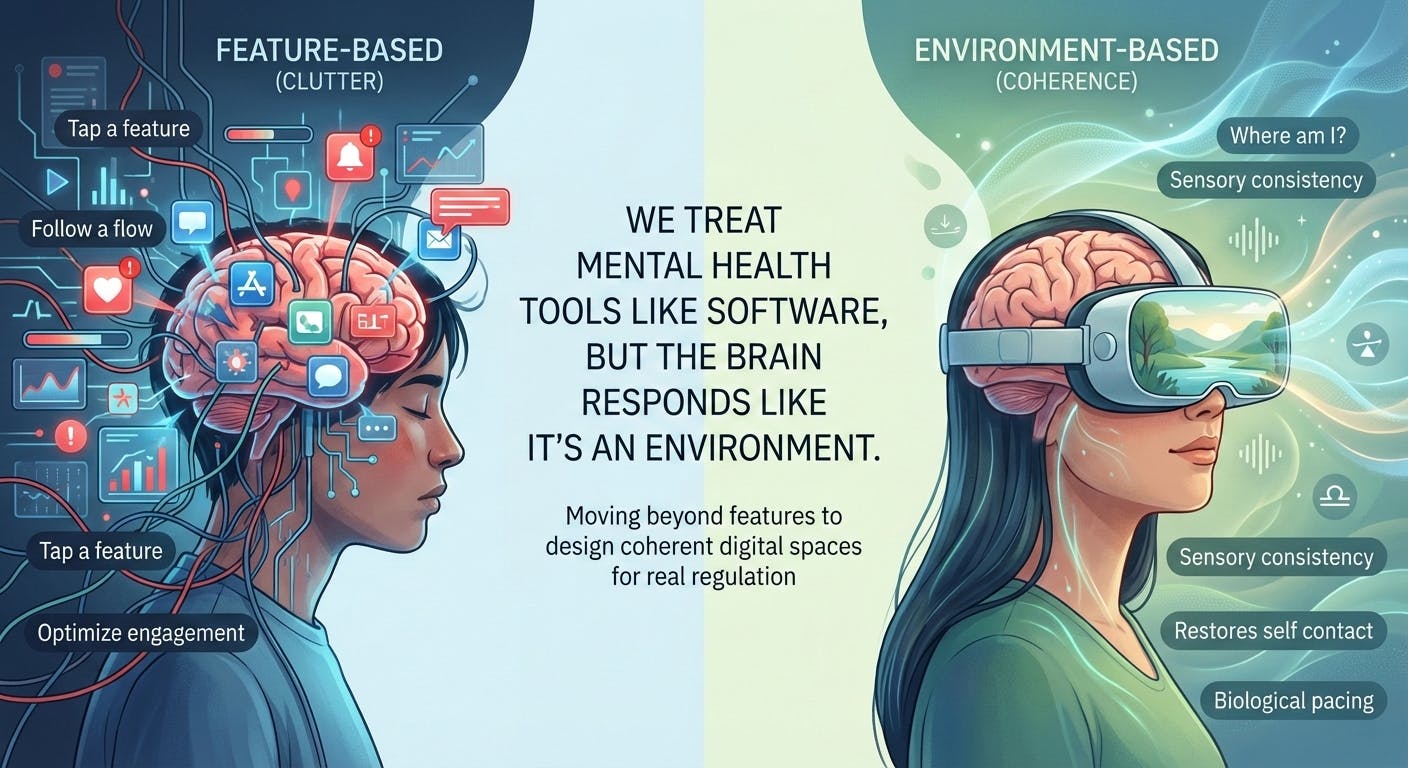

We build tools the way we build software. We assume the mind is a user with a problem to solve. Tap a feature, follow a flow, get an outcome. Calm. Focus. Relief.

But the brain does not experience these products as software.

It experiences them as an environment.

That difference is not poetic. It is structural. It explains why so many digital interventions feel helpful at first, then flatten out, even when the UX is good and the personalization looks impressive.

My research and clinical work with immersive formats keeps pushing me to a simple conclusion. The nervous system does not ask, “What feature am I using?” It asks, “Where am I, and what does this place demand of me?”

I stopped thinking in features. I started thinking in spaces.

When I began studying how people respond inside virtual environments, it became obvious that content is only half the story.

The other half is the container. Sensory consistency, rhythm, predictability, symbolic coherence. These elements shape regulation long before a person evaluates the exercise intellectually.

This is why two tools with the same intention can produce opposite results. A breathing practice inside a noisy digital ecosystem does not land the same way as that same practice inside a stable, emotionally aligned environment.

Once you see the brain as a system in a space, a lot of product patterns start to look fragile.

Why feature based mental health design keeps stalling

Most mental health technology is built like productivity software.

Identify a state.

Deliver an intervention.

Optimize engagement.

The flaw is that the brain does not apply interventions in isolation. It integrates signals across time. If the surrounding environment remains fragmented, urgent, and attention hungry, a calming feature becomes a temporary patch.

This is the adoption curve I see repeatedly.

People feel relief early.

They engage for a while.

Then the effect fades.

It is not because the feature stopped working. It is because the broader digital environment never stopped pulling the nervous system into compensation.

I

If the baseline context stays chaotic, the person returns to their baseline.

Digital spaces shape identity, not just mood

This is the part most products avoid.

Every environment answers a quiet question for the user. Who am I when I am here?

Social media answers it through comparison. Productivity tools answer it through performance. A lot of mental health apps try to skip the question and aim directly at symptoms.

But identity is not optional in real recovery. When a person goes through prolonged stress, burnout, or serious illness, they are not only trying to feel better. They are trying to locate themselves again.

In my

When a tool treats users like task runners, it can unintentionally reinforce disconnection. It gives actions without restoring orientation.

Immersion is not automatically helpful. Sometimes it is the problem.

Tech culture often equates immersion with impact.

More presence. More realism. More intensity.

I do not treat immersion as inherently positive. I treat it as power.

And power needs safety logic.

Immersion can regulate. It can also overwhelm. If sensory intensity exceeds the nervous system’s capacity to integrate, the experience can trigger fatigue, agitation, or subtle dissociation, even if the content is “positive.”

That is why neuropsychological safety matters. It is not the same as ethics checklists or content moderation. It is about knowing what immersive environments do to attention, arousal, and self contact.

I wrote directly about this in my paper on the ethics of immersion and neuropsychological safety in virtual therapeutic environments.

https://www.вестник-науки.рф/archiv/journal-8-89-4.pdf

I would summarize the point like this. The nervous system does not benefit from being impressed. It benefits from being oriented.

What I look for now when I design or evaluate a mental health product

When I stop thinking in features and start thinking in environments, the evaluation criteria change.

I ask:

Is this space predictable?

Does it reduce cognitive load or add to it?

Does it respect pacing or force intensity?

Does it restore self contact or keep the person in performance mode?

Does it create coherence over time or just deliver short moments of relief?

One of the most important concepts for me here is self contact. Under chronic stress and burnout, people often lose the felt sense of internal continuity. They become functional, but not present.

In my

That is a different mechanism than most apps assume.

It is not advice. It is environmental regulation.

The next generation of mental health tech will be environmental, not functional

AI will make it easy to add more features.

More personalization. More adaptivity. More conversational intelligence.

But I do not think the core bottleneck is intelligence. I think it is environment quality.

If the digital space is fragmented, urgent, and cognitively noisy, a smart intervention will still underperform biologically. It will feel like a patch placed inside a system that keeps reactivating the same stress patterns.

The future of mental health technology, in my view, will be defined by calmer, more coherent digital spaces.

Spaces designed with biological pacing. Spaces that use sensory logic, symbolic coherence, and safety constraints as first class design requirements.

Not because it sounds humane.

Because it is how the brain actually works.

Until we design for that, we will keep building tools that technically function, while the nervous system treats them as another place that demands too much.

And we will keep wondering why the product roadmap promised progress, but the person inside the system keeps reverting to baseline.