The internet has never felt louder, yet the people inside it have never been quieter.

Open any app, and your feed is a wall of ads, viral clips, AI-generated faces, and hyper-polished “content,” but the messy, everyday life updates from actual friends seem to have vanished.

I have felt this change in my own circles.

Timelines/feeds that were once full of birthdays, bad selfies, random cat/dog/food photos, and half-baked thoughts are now strangely still, even as everyone quietly keeps scrolling.

Have we already passed peak social media?

Recent data suggests that the world may have already passed peak social media, at least in terms of time and enthusiasm.

A large analysis commissioned by the Financial Times and conducted by digital insights firm GWI looked at the online habits of around 250,000 adults across more than 50 countries and found that average time spent on social media peaked in 2022 and has since fallen by almost 10%.

Even after that drop, people in developed countries still spend roughly two hours and twenty minutes a day on social platforms, which is a staggering amount of attention.

What is even more interesting is who is driving that decline.

The steepest drop-off is among teenagers and people in their twenties, the very generations that made social media mainstream in the first place.

The same analysis also notes a clear shift in why people open these apps: using social media for conversation, self-expression or meeting new people has fallen sharply since 2014, while opening apps just to “kill time” has risen.

In other words, social media is becoming less social and more like a background habit.

From oversharing to “posting zero.”

A decade ago, if you remember, feeds were chaotic but recognisably human.

People posted terrible food photos, blurry concert stories, gym mirrors, and long rants that nobody really needed to read.

I remember my college days, when many teens and even adults used to treat social media as a default diary of their existence.

It was noisy and unfiltered, but it felt like walking into a crowded café where everyone was talking at once. Now, a lot of those voices have gone silent.

Now, many younger users are quietly shifting to what Kyle Chayka calls “posting zero” approach, meaning still on the platforms, still scrolling, but barely posting anything about their own lives (a purely consumptive mode).

The reasons are layered. There is a growing fear of misinterpretation or online backlash.

One awkward joke or badly phrased caption can be screenshotted, shared, and turned into a permanent stain on your digital identity.

At the same time, recommendation-based feeds mean that even if you do post, there is no guarantee that your friends will ever see it, which makes sharing feel both high-risk and low-reward.

Lurkers in a performative internet

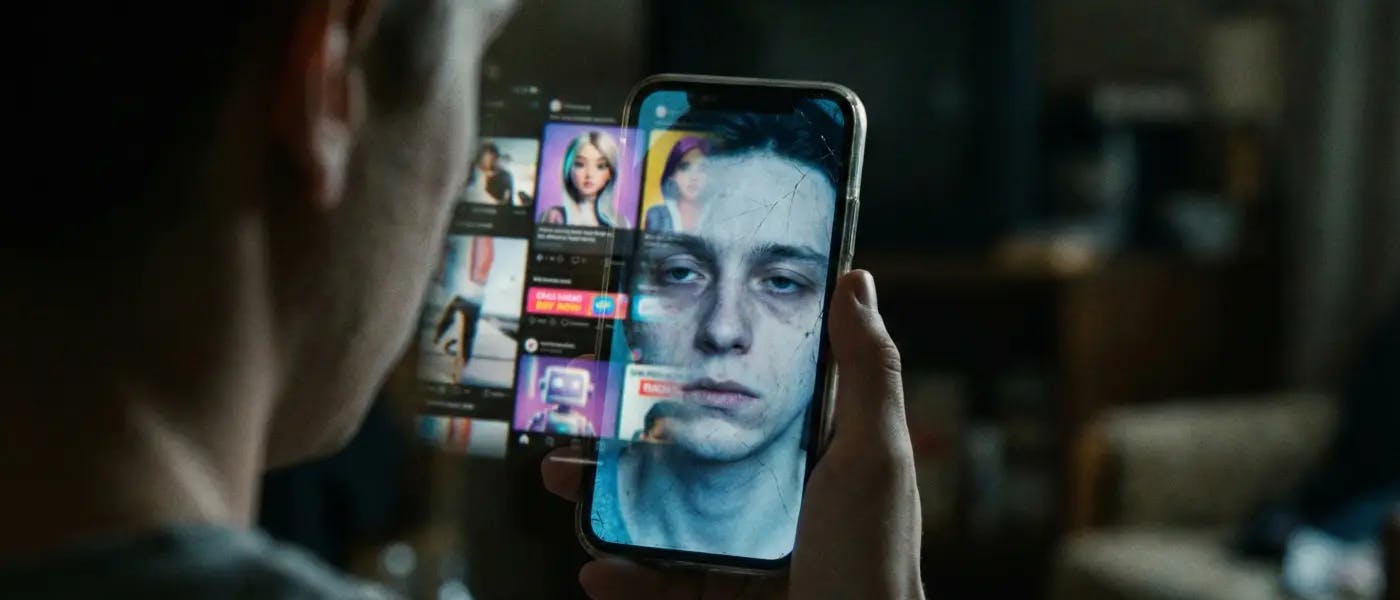

This has quietly produced a world of “ghost participants.” People who spend hours watching but rarely, if ever, step on stage.

They lurk behind the glass, tapping through stories, liking posts, or just swiping without interacting at all.

In my own life, I notice that people I talk to every week almost never publish anything, yet they know exactly what is happening online because they are always there, invisibly observing.

The emotional climate also matters. It is hard to post your beach holiday or brunch when the news cycle is full of wars, protests, disasters and economic anxiety.

During and after the pandemic, researchers began to use the word doomscrolling to describe compulsively consuming negative news, often late at night, and linked it to higher psychological distress and lower life satisfaction.

For a lot of Gen Z and younger millennials, posting something light-hearted in the middle of this constant crisis feed can feel tone-deaf or even morally wrong, so they retreat into silence while continuing to scroll.

The feed that stopped feeling human

Another less philosophical reason people post less is that “feeds no longer feel like places for them.”

Over time, major platforms have shifted from showing mostly friends’ updates to showing whatever maximises engagement, often a mix of influencers, brands, and algorithmically supercharged content.

Policy and technical analyses of recommender systems have shown that these algorithms are explicitly optimized for engagement metrics such as watch time, clicks and reactions, because those are the numbers that drive advertising revenue.

That optimisation changes what we see.

Instead of your cousin’s bad vacation photos, you get a real-estate guru promising you can retire at 30, a dozen skincare ads, and an AI-generated model who never existed outside a graphics card.

Reports on AI-driven social media note that recommendation engines are trained on your every interaction (likes, pauses, rewatches), to assemble a hyper-personalized stream of content meant to keep you from looking away.

It’s efficient, profitable, and increasingly inhuman.

I have explored a slice of this dynamic in “Instagram Blend Is Supposed to Bring Us Closer, But It’s Doing the Opposite,” where a feature built to deepen connection ends up amplifying distance instead.

The “dead internet” feeling: bots, brands and AI slop

If your feed feels strangely artificial, it is not just your imagination.

A Thales report estimates that nearly half of all global web traffic in 2023 came from bots rather than people, with about one‑third of all traffic attributed to “bad bots” engaged in scraping, spam, and various automated attacks; human traffic, by contrast, fell to just over 50%.

When you mix that scale of automation with AI-generated text, images, and videos, you get what many users describe as a “dead internet” vibe: feeds clogged with content mills, synthetic faces, and engagement farms rather than real human voices.

The result is a strange paradox. The internet has never produced more content, but it has never felt more hollow.

In that environment, choosing not to post feels less like withdrawal and more like a quiet act of self-respect.

Meanwhile, the scrolling never stopped

Here is where the contradiction bites.

People may be posting less, but the scrolling is still relentless.

I have watched this with my own family. A few years ago, my father barely used the internet.

Now he can sit for hours flicking through short videos and reels, hypnotized by an endless cascade of clips that blur into each other.

This doomscrolling has become the new smoking for people like him, and they don’t even realize that.

I also see children in my wider circle refusing to eat unless a phone is playing YouTube Shorts in front of them.

Research backs up this uncomfortable picture.

Recent studies on short-form video platforms such as Reels, TikTok and YouTube Shorts have found that heavier use is linked to reduced attention, weaker impulse control and small but measurable declines in memory and working memory across both teens and adults.

A 2024 study on university students reported that frequent reel-watching was associated with shorter attention spans and lower academic performance, especially among those who spent several hours a day on these platforms.

Neuroscience-focused work has also tied short-video addiction to changes in the brain systems responsible for self-control, suggesting that prolonged exposure may train the brain to expect constant stimulation and make sustained focus more difficult.

Everything you scroll is perfectly engineered

Underneath this epidemic of doomscrolling sits a very specific design decision. AI systems are now in charge of who we are, what we see, for how long, and how intensely they hook us.

These recommendation engines track every micro‑gesture (what we like, how far we scroll, where we pause, which clips we replay), and use machine learning to predict the exact sequence of posts most likely to keep us glued to the screen.

In practice, that creates a self-reinforcing loop.

The algorithm serves up content that spikes novelty or emotion, the brain’s reward system fires, and that neurological response becomes fresh training data to make the feed even more irresistible next time.

Over weeks and months, this pattern stops looking like casual use and starts resembling behavioral addiction, a concern clinicians and digital addiction researchers now raise explicitly when they talk about AI-optimized feeds for teenagers.

If I have to put it in plain language, the system is built to keep you scrolling, not to help you stop.

That is what makes the role of AI so paradoxical.

In hospitals, deep learning AI models detect breast cancer tumors, often matching and sometimes exceeding the performance of human radiologists.

The same families of techniques (massive datasets, deep neural networks, endless optimisation cycles) are then redeployed to tune late-night feeds that watch you linger on outrage, fear or envy and respond by feeding you more of the same.

If we applaud AI for helping save lives in radiology suites, we also have to reckon with how it quietly shapes our attention, amplifies our cravings and, in many cases, reinforces our addictions on the very phones we hold in the waiting room.

Can we make the internet feel human again?

So where does that leave us?

If people are posting less but scrolling more, it suggests that the desire to observe has outlived the desire to participate.

Part of that is fatigue, part of it is fear, and part of it is the architecture of the platforms themselves.

I do not think we can fix this purely at the individual level, by telling people to have more “discipline,” while the default design of the system is to overwhelm their discipline.

What can change is the set of expectations we have from ourselves, our communities, and our regulators.

Recommendation systems can, in principle, be optimized for well-being metrics instead of raw engagement, and research organisations have already proposed frameworks for doing exactly that.

Public health guidance can treat doomscrolling and digital addiction the way it treats sedentary lifestyles or unhealthy food environments: not as purely private choices but as patterns shaped by industries and infrastructures.

At a personal level, the quiet rebellion might be this:

- post something small and imperfect to the few people you actually care about

- mute the feeds that make you feel like a product

- set hard edges around when you scroll and when you don’t.

None of that will fix the internet overnight, but it is a way to insist that this space belongs to people first, not to brands, bots or engagement graphs.

The real internet, the one built from stupid jokes, bad photos, and honest conversation, will only come back if we decide that being human online matters more than being optimized.