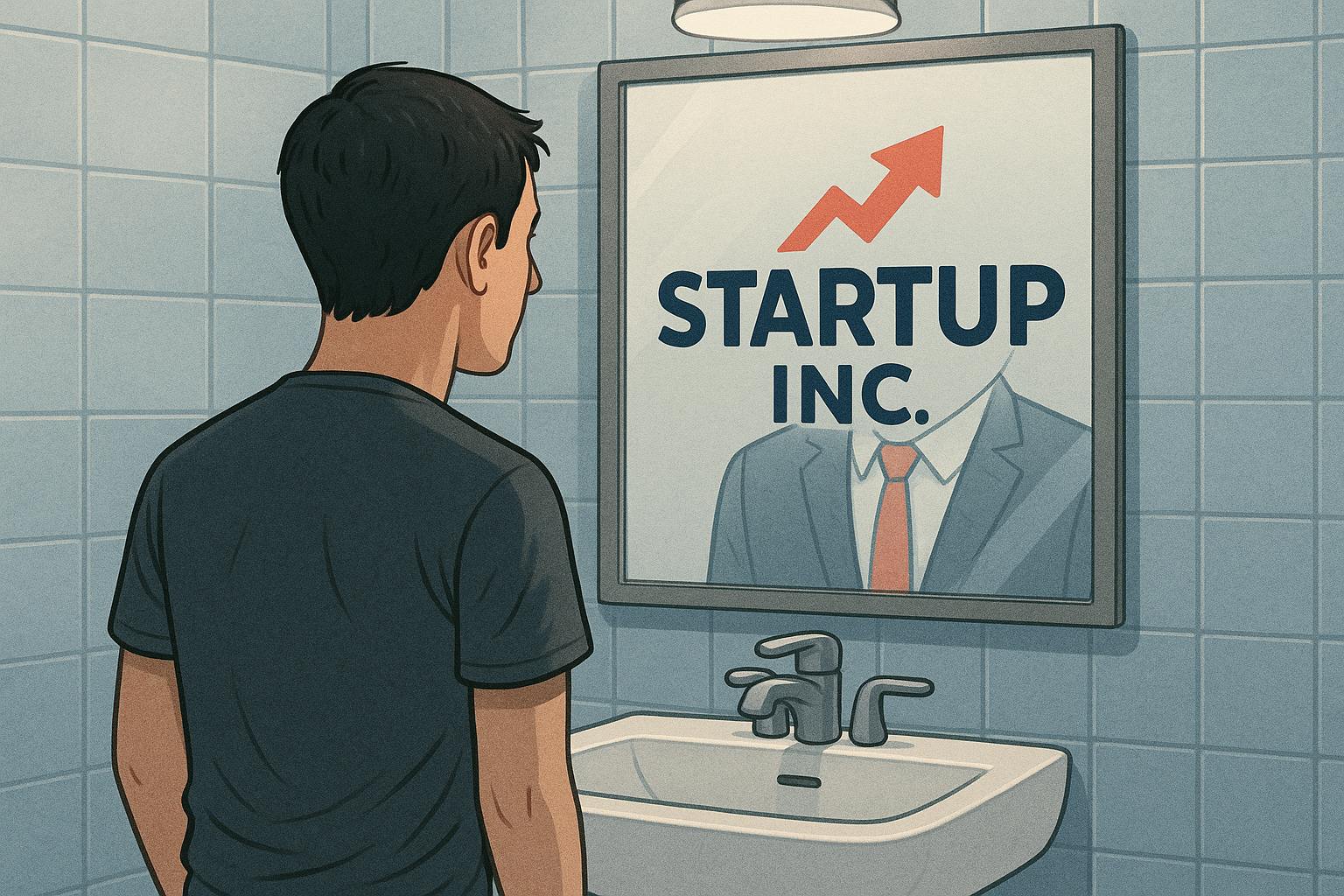

It feels noble to give yourself entirely to your company.

That’s what every founder does, right?

You want to be obsessed. Outwork everyone. Late nights. Make the impossible happen through sheer force of belief. It’s practically a rite of passage.

And early-stage investors love to reinforce this narrative by claiming they’re “investing in the founder.”

That fusion between founder and startup is, early on, an edge.

If you’re a founder who really owns it, your pitch isn’t just about the product. Every milestone feels like personal growth. The company roadmap starts to feel like your future autobiography.

The intensity from that identity merge is often what gets early-stage companies from nothing to something. It’s what gets investors to write you the check and what gets employees to leave safe jobs. But we rarely talk about how that fusion often goes from an edge to a serious blind spot.

A Real Identity Crisis

When a company is doing well, this most often shows up when it’s time for the founder to take a step back.

Maybe the business is growing faster than the founder, and it’s time for a seasoned operator. Maybe the founder themselves is burned out and ready to take a different role (at least on paper).

However much sense the decision might make, it’s emotional and anything but simple.

After all, the founder identity is intoxicating. You’re “the reason” it all exists. You’re the story the investors bet on. You’re the one in the headlines, on stage, in the group chat when things go right. So, how do you “hand off” something that feels like you?

How do you detach when the product reflects your worldview, your taste, your habits, your wiring? How do you sit in a boardroom and objectively assess your own usefulness?

It can feel like losing the very thing that made you matter.

When the Merge Becomes the Meltdown

Even more dangerous is when things at the startup aren’t going well: because if the startup is you, then failure becomes a personal, existential threat. And that’s dangerous.

Forced into a corner, you may enter a survival mode where you’ll go to great lengths to avoid bad news or defend weak decisions. And in that survival state, objectivity disappears.

I know that better than anybody.

When my adtech company was in a tailspin five years ago, I completely lost the thread and told myself a dangerous lie: that my company’s fate was my fate.

I entered a reactionary mode and went to incredible lengths to protect myself.

I wasn’t at risk; the startup was. But I couldn’t tell the difference.

The Importance of Maintaining Objectivity

The key to decoupling founder from company - to finding the off-ramp before things go off the rails - is good old-fashioned objectivity.

That’s not just the ability to see the business clearly, but to see yourself clearly within it. To know when your presence is driving the startup forward and when it’s holding it back. To recognize when you’re making decisions in service of the mission, and when you’re making them in service of your ego.

Easier said than done.

Objectivity in the startup environment doesn’t necessarily come naturally, especially not in environments that reward belief over balance and treat founder obsession like a virtue. If you want to stay grounded, you have to work at it intentionally, consistently, and with humility.

The founders who figured this out:

- Build identity outside the business. They invest in relationships, creative pursuits, and personal goals that have nothing to do with KPIs or pitch decks. The startup matters—but it’s not the only thing that defines them.

- Engage in honest internal dialogue. They ask hard questions like, “Am I the right person for this stage?” or “What would I tell a founder friend in this situation?” - and they don’t rush to justify the answer.

- Create feedback loops that live outside the hype. Mentors, advisors, therapists, and other people who aren’t caught up in the company’s narrative gravity. These are the people who won’t flatter you. They’ll challenge you.

Perhaps most importantly, they allow themselves to imagine the startup without them - whether that means it thrives or fails.

Because real leadership isn’t about holding on. It’s about knowing when to let go.